Corps Diplomatique | In today’s world of ‘leaks’, data is king; a commodity which is deliverable and whistleblowers are messengers that need all type of judicial and legislative protection

Information has always been a commodity. Throughout history, kings, rulers, dictators, governments, journalists, the civil society and other forms of ‘systems’ and their antithesis have looked upon information as perhaps the second most lethal weapon beyond militaries themselves. However, this is now changing. Information trumps classical military might, as the latter becomes only a means to an end.

Information today manages many spheres, from international taxation and global finance in London to drone warfare in the badlands of the Afghanistan-Pakistan borders, it is the desire of accurate, and deep information that today drives policy, decision making and most other aspects of our lives as both commercial and personal technologies develop at a furious pace.

Historically, ‘leaks’ of data and information have caused both wars and end of wars. For example, as far back as in 1848, details about the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, an agreement which was to conclude the two-year long Mexican–American war, was leaked to a journalist named John Nugent of the New York Herald (which seized publication in 1924). Nugent was held without charges for over a month and was interrogated to release the name of his source, which he refused to do so. According to a TIME magazine article, evidence suggests that the then US President James Buchanan, in his previous role as the Secretary of State, was most likely the ‘leak’ himself.

Since then, many such cases have come to light and the early 1970s in the US perhaps set a precedence of mainstream ‘data dissent’, the information being leaked to stall a government’s policy juggernaut or a politician’s overreach. The Pentagon Papers in 1971 where Daniel Ellsberg, a researcher with Massachusetts’s Institute of Technology’s Center for International Studies leaked to The New York Times 3,000 pages of narrative and 4,000 pages of appended documents, officially titled ‘Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force’, commissioned by then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in 1967. Ellsberg was charged with espionage but later exonerated in 1973. Later on, the world famous Watergate scandal unfolded in Washington, which led to the purge of Richard Nixon as the President of the US. A mysterious informant only known as ‘Deep Throat’ had provided The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with leaks that led to the scandal. ‘Deep Throat’ was later in 2005 confirmed to be W Mark Felt, a former FBI special agent who retired as the bureau’s deputy director in 1973.

However, today, leaks and ‘data dissent’ have come of age. In an era where paper trails have been replaced by binary language data highways, information collection, and dispersion has become easy, but providing safety for the same has become a challenge as the concept of a lock and key does not exist in the new cyber warfare era. The modern Guy Fawkes of the digital era perhaps just requires a capacity USB drive, which can fit into a small pocket within a wallet, to bring millions of secretive documents or data into the public sphere.

The Panama Papers

In Munich, the capital city of Bavaria in southern Germany, one-day two investigative journalists of the Suddeutsche Zeitung newspaper, Bastian Obermayer, and Frederik Obermaier, received a simple, encrypted, straightforward message: “Hello. This is John Doe, are you interested in secret data?”

What this ‘introduction’ led to was the world’s largest data leak ever, as the source John Doe released millions of documents from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca detailing how the world’s elites squandered money and saved millions by avoiding paying taxes in tax havens around the world while seriously challenging and manipulating, often at will, the global financial systems. These leaks brought into light thousands of names of people, entities, companies who employed these methods to stash money away in such tax havens. In fact, in the case of Mossack Fonseca, the leaks also showcased how the firm ran an entire island country of Niue in the southern Pacific Ocean as a tax haven from start to finish.

John Doe, the whistleblower who till date remains anonymous, in his manifesto, declared that income inequality is one of the defining issues of our times. The whistleblower says it could take years and even decades for Mossack Fonseca’s crimes to be brought to justice. John Doe adds:

“Banks, financial regulators, and tax authorities have failed. Decisions have been made that spared the wealthy while focusing instead on reining in middle- and low-income citizens.

Hopelessly backward and inefficient courts have failed. Judges have too often acquiesced to the arguments of the rich, whose lawyers—and not just Mossack Fonseca—are well trained in honoring the letter of the law, while simultaneously doing everything in their power to desecrate its spirit.

The media has failed. Many news networks are cartoonish parodies of their former selves, individual billionaires appear to have taken up newspaper ownership as a hobby, limiting coverage of serious matters concerning the wealthy, and serious investigative journalists lack funding.”

In India, the Panama Papers did not create the ripples that one would have expected. In fact, this view could be held for most other countries as well, even as John Doe himself suggested that he was slightly disappointed with the progress. But this is also perhaps because the nature of this data is very different, and in fact owning shell companies abroad may not illegal in itself, it is what a person does with it what needs thorough, expensive and time-consuming investigations. It is ultimately in the hands of governments to act on what the Panama Papers have presented, and a lot of the evidence against tax havens is damning because a lot of these tax havens are Western influenced. A direct effect of these leaks was a global anti-corruption summit organized, ironically, in London, which is perhaps the world’s largest parking slot for oligarchic money. Led by British Prime Minister David Cameron, whose own family’s name appeared in the Papers, the London conference started and finished in a blink of an eye, and leaves journalists at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) hoping that all this collective work worth months of hardship leads to legislative changes in the future. And in fact, there may be signs of such an outcome, with institutions such as European Parliament agreeing to set up an official inquiry to look into the claims raised by the Panama Papers.

Often it is asked why Panama Papers, despite being the biggest leaks with the potential to disrupt global financial systems, did not get the due mileage, specifically in a highly corrupt system like India. The answer is simple. Previously, most high-profile leaks have come from the intelligence sectors. Both Julien Assange’s Wikileaks (which was also reportedly offered the Panama Papers, but refused) and Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks involved intelligence and military secrets in large numbers. States will always offer a much stronger and immediate blowback on such issues than finance, banking, taxation fraud and so on. Also, Panama Papers deal with highly specialized topics such as tax laws, international finance, creative accounting and so on. All these topics under the ambit of the international system offer more grey areas to search than black and white ones.

The Whistleblower: Can India have its own Edward Snowden?

“This was a huge flaw in the past, that journalists knew how to deal with the information but did not know how to protect the whistleblower,” Obermaier recently said.

Whistleblowers are not uncommon and have never been. On a small scale, whistleblowers take on battles on a daily basis, but the cases of Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning and now ‘John Doe’ have only highlighted this due to scale. But the important thing here to note is that all these whistleblowers were prosecuted, or are on the run like Snowden who for now resides in Moscow. But John Doe is not the first one who has looked to wade through the much in global money laundering, previously whistleblowers like Antoine Deltour who exposed how Luxembourg sanctioned tax avoidance by the world’s largest businesses and Herve Falciani who exposed more than 130,000 suspected tax evaders from Swiss bank accounts, specifically those with HSBC Bank’s Swiss subsidiary HSBC Private Bank (‘The Bank Robber’, a The New Yorker magazine profile of Falciani is highly recommended reading).

Whistleblowers in India are not a new phenomenon either, and India is also one of the few countries, which in 2011 introduced a Whistleblowers Protection Act (WBP). However, the mechanisms of this act are on a head-on collision with the Official Secrets Act (OSA), which looks to undermine WBP enough in order to make potential whistleblowers think thrice before taking a move in that direction. However, this is still pending clearance in the Rajya Sabha.

Fact is that India has had many whistleblowers over the past years that have blown the lid on corruption, and this includes civil society, activists, and bureaucrats. The Vyapam scam has been an ongoing example of how whistleblowers do not have near enough protection in the country on such matters. Anonymity is one way of going about such problems, however, Indian ecosystem perhaps does not allow for such a way forward and this is where technology can come into great use.

“A life of a person is more important than reporting. You can’t wage a life against reporting,” Obermaier had stated when asked about whistleblower protection, and he also highlighted that this was the reason why they had refused to meet John Doe, and would continue to advise the source to remain anonymous even to them.

Ultimately, in today’s world of ‘leaks’, data is king; a deliverable commodity and whistleblowers are the messengers that need every kind of judicial and legislative protection, in this case, in order to re-color the massive grey areas in the global financial systems. Comparatively, issues such as the Panama Papers offer a much more approachable and manageable fight, for both governments and civil society, than what the Snowden leaks sought out to do.

![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'

Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...

Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...![submenu-img]() 'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral

'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts

Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts![submenu-img]() Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh

Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, Sonali Bendre celebrate 25 years of Sarfarosh, attend film's special screening

Aamir Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, Sonali Bendre celebrate 25 years of Sarfarosh, attend film's special screening![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'

Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...

Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...![submenu-img]() 'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral

'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral![submenu-img]() First Indian film to be insured was released 25 years ago, earned five times its budget, gave Bollywood three stars

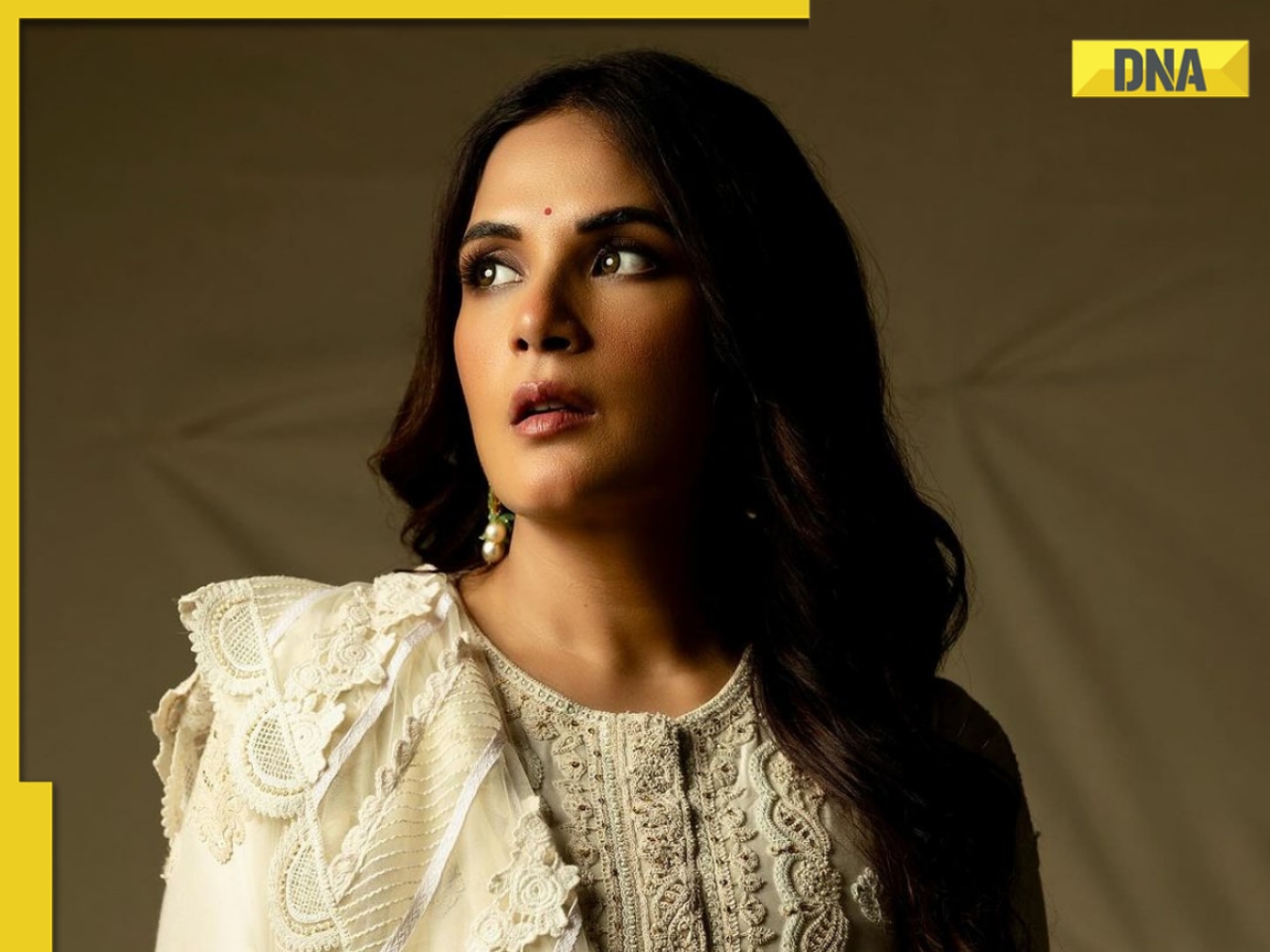

First Indian film to be insured was released 25 years ago, earned five times its budget, gave Bollywood three stars![submenu-img]() Mother’s Day Special: Mom-to-be Richa Chadha talks on motherhood, fixing inequalities for moms in India | Exclusive

Mother’s Day Special: Mom-to-be Richa Chadha talks on motherhood, fixing inequalities for moms in India | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Kolkata Knight Riders become first team to qualify for IPL 2024 playoffs after thumping win over Mumbai Indians

Kolkata Knight Riders become first team to qualify for IPL 2024 playoffs after thumping win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: This player to lead Delhi Capitals in Rishabh Pant's absence against Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: This player to lead Delhi Capitals in Rishabh Pant's absence against Royal Challengers Bengaluru![submenu-img]() RCB vs DC IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs DC IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() CSK vs RR IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs RR IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Delhi Capitals

RCB vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts

Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts![submenu-img]() Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh

Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh![submenu-img]() Man grabs snake mid-lunge before it strikes his face, terrifying video goes viral

Man grabs snake mid-lunge before it strikes his face, terrifying video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man wrestles giant python, internet is scared

Viral video: Man wrestles giant python, internet is scared![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi University girls' sizzling dance to Haryanvi song sets the internet ablaze

Viral video: Delhi University girls' sizzling dance to Haryanvi song sets the internet ablaze

)

)

)

)

)

)

)