Knowledge will forever govern ignorance and people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power that knowledge gives.

Knowledge will forever govern ignorance and people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power that knowledge gives. A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it is but a prologue to force or a tragedy, or perhaps both.

Need for RTI

Theoretically, right to information (RTI) recognises that every person has a guaranteed right to access information held by the government. Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution guarantees fundamental rights to free speech and expression.

The pre-requisite for enjoying this right is knowledge and information. The absence of authentic information on matters of public interest will only encourage wild rumours and speculations.

Thus, RTI has been given the status of a constitutional right to free speech and expression, which includes the right to receive and collect information, helping the citizens perform their fundamental duties as set out in Article 51(a) of Constitution.

RTI has already received judicial recognition as a part of the fundamental right to free speech and expression and right to liberty. However, an act was necessary to provide statutory framework to lay down the procedure for translating this right into reality.

Passing of the Act: The RTI Bill replaced the Freedom of Information Act 2002 that was never implemented. The Act became operative from October 12, 2005.

Critical evaluation

The strength of RTI is judged on the basis of five parameters:

1. Application of the Act:

Under the Act, right to information is given only to a citizen of this country, though no such restriction is made in most countries.

Information can be obtained only from a public authority. The Act specifically excludes information from private authorities. In the era of privatisation, not providing for access to private information is less than desirable.

2. Accessible information:

The Act defines ‘information” but “file noting” has been excluded from the purview of the definition of “information and record.”

There was wide criticism on this count, leading the government to make some discounted changes. On December 1, 2005, under the instruction of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, it was decided to incorporate certain changes in the rules under the RTI Act.

It was decided that “file noting” relating to identifiable individuals, group of individuals, organisations, appointment matters relating to inquires and departmental proceedings shall not be disclosed.

3. Severability:

Section 10 of the RTI Act provided relief to save the requests for information from the rigidity of exemptions mentioned in S.8 and S.9.

The provision is excellent and is universally followed. However, two changes are suggested: a) Decision to sever must also be subject to appeal, and b) The document should be made available in its original copy after blacking out the severable portions.

Suo moto disclosure: Suo moto disclosure is one of the most important provisions of the RTI Act; public authorities are to give reasons for decisions, publishing and communicating to the persons likely to be affected and the relevant information available before initiating the projects.

The law should establish both a general obligation to publish and key categories of information that must be published.

Exemptions: No right is absolute. The Act has provided a long list of documents, material or information, which cannot be accessed.

Section 8 and Section 9 of the Act together provide about 11 grounds of exemption, some of them such as threat to security of the state, disclosure expressly forbidden by the court, personal information, information held in fiduciary relationship etc.

However, provisions pertaining to commercial secrets contained in Section 8(d) appear innocuous. Also, there is no need to exempt Cabinet papers from disclosure if they compromise public interest.

Exempted organisations: Section 24 gives power to the government to add a list of organisations to which the Act does not apply. The power given under this section is too wide and unnecessary, and may also be said to be devoid of any rationale. Surprisingly, the list also includes the police force.

Overriding provision: It is necessary to make an overriding provision that any information, which cannot be denied to the Parliament and State Legislature, will not be denied to any citizen.

The Act contains a similar provision, but it is only as a proviso, thus limiting its application to personal information of public interest. This provision should have an overriding effect on all other exemptions.

4. Institutions and adjudicating authorities:

The most outstanding provision of the RTI Act is the appointment of an information commission. A high level commission is dedicated to implementation of the Act. The Act also envisages a chief information commissioner appointed by the Leader of the Opposition in Lok Sabha and Chief Justice of India.

Public information officer: Another good feature is that it provides for the executive to enforce the freedom of information.

It authorises public authority to appoint public information officers, who shall deal with requests for information.

However, Section 5 does not mention the level in the administrative ladder at which the information officer should be appointed. It is also not clear if the public information officer can decide to give or withhold information unilaterally, or if there will be some internal system.

Adjudicatory authority: One of the serious weaknesses of the Act is that there is no provision for an appeal to an independent authority.

Both the appeals are to the government itself. Section 23 of the Act also bars the jurisdiction against the orders passed under this Act. Thus, the only remedy against the orders passed in appeal by the government would be to approach the High court or Supreme Court by means of writ jurisdiction, a remedy that would be impractical for most citizens.

5. Penalties:

The Act makes it clear that subject to certain safeguards, there is public interest in allowing access to such information.

The Act lays down a general duty for public officers to provide information and the failure to do so attracts penal liability to the tune of Rs 250 per day. However, it fails to check vexatious or repetitious requests for information as it does not absolve the public officer from this duty; nor does it provide penalty for such requests.

Conclusion

With the passage of the Act, an important right has now been recognised by the Parliament. There is, however, a long struggle ahead before this Act becomes an effective instrument for securing the citizens’ right to information and bringing about transparency in functioning of the government and its agencies.

The right to part with information will require a change in the mindset of legislators and bureaucrats for whom secrecy in governance is a prime legacy. Information is power and it really takes courage to share it.

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

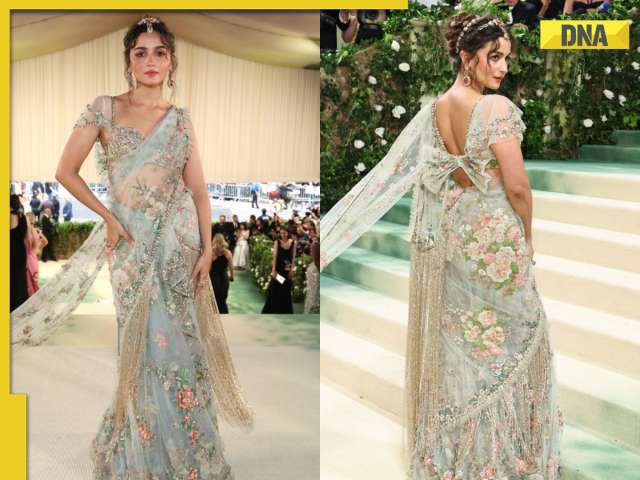

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

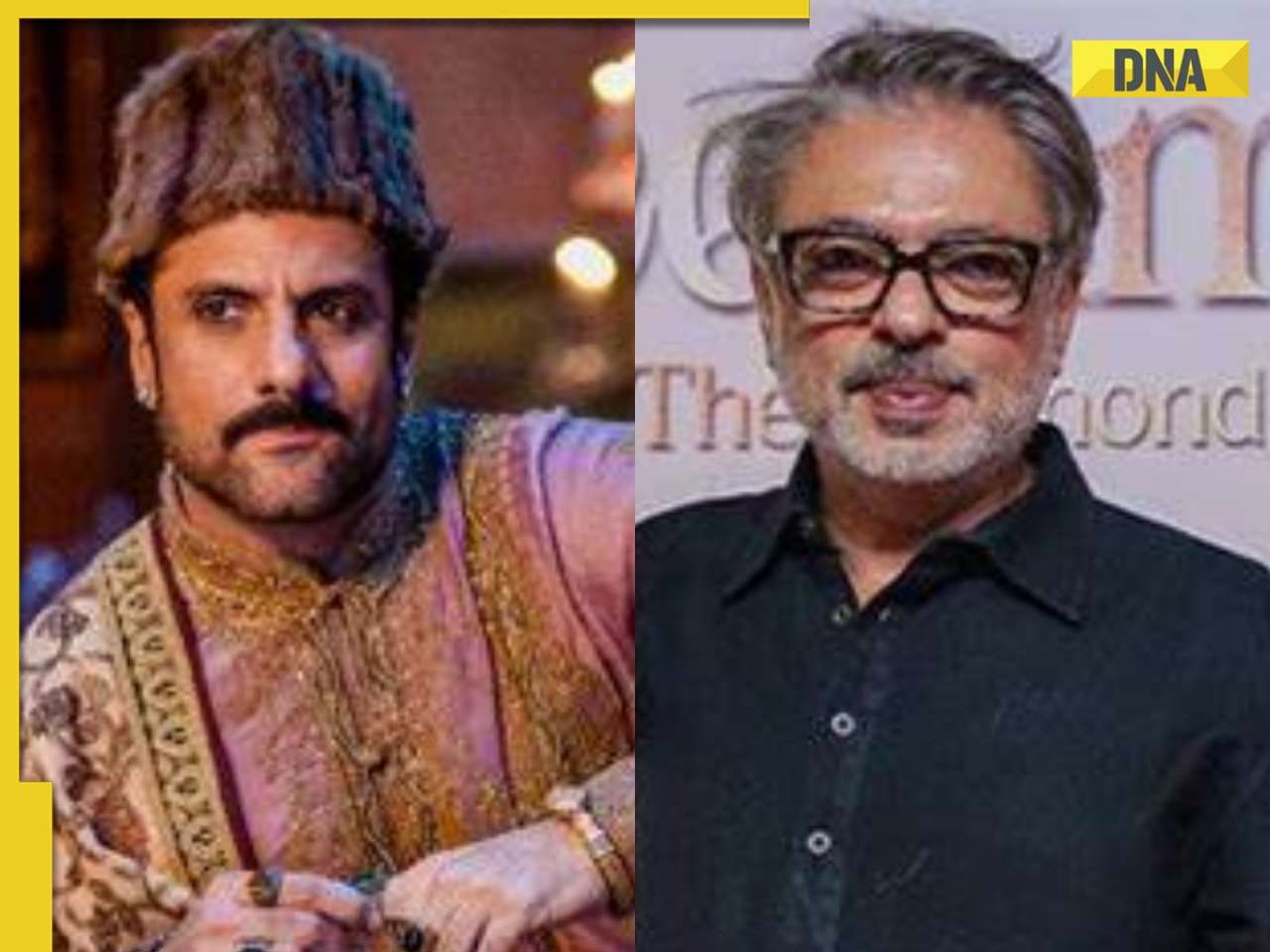

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)