Towering personalities that they were, members of India’s first cabinet couldn’t avoid ego clashes.

Great men, greater egos, is what free India's first cabinet was all about. In Part-III of the Nehru archives series, DNA's Josy Joseph delves into the era's red tape, its rising star and the Nizam's golden gift

Towering personalities that they were, members of India’s first cabinet couldn’t avoid ego clashes. And even the heavyweights scurried to prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru with their complaints.

The first set of PMO files, declassified after independence and exclusively with DNA, record at least two spats between two pairs of senior cabinet members. It not merely reflects ideological differences, but also the bureaucratic stranglehold.

Nehru wrote on February 19, 1948, to his finance minister Shanmukham Chetty, “The other day your ministry gave their consent to the appointment of a consul general in New York. This recommendation had been sent a considerable time ago from external affairs. It has been rather an urgent matter and it was delayed because the finance ministry took a long time over it.”

Nehru goes on to draw Chetty’s attention to the education ministry under Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, “I am told that a very large number of files from the education ministry have been in the finance ministry for many months and some for over a year. Indeed some proposals have simply lapsed because of this delay. You will agree with me that any system which leads to proposals being hung up for a long time is not satisfactory.”

Noticeably prompted by Azad, who formally wrote to Chetty a few weeks later, Nehru suggests they “devise a quicker way of dealing with proposals emanating from various ministries which go to the finance ministry for approval. In particular I shall be grateful if pending matters from the education ministry are examined and expedited.”

Chetty in his reply to Nehru says, “I am also enclosing a copy of my letter to Maulana Sahib in which I have made some suggestions for strengthening the education ministry also, so that proposals emanating from them reach the finance ministry in a form capable of rapid disposal without considerable difficulty in assessing the full implications of the proposals...Normally, the administrative departments themselves fully scrutinise all administrative and financial implications of any proposals they wish to put forward, and they are presented to the finance ministry in a manner capable of their appreciating all the implications without considerable difficulty. Unfortunately, proposals from your ministry are not presented to the finance ministry in the same manner as from other ministries,” Chetty writes to Azad on March 20, 1948.

On March 22, Nehru replies to Chetty saying, “The fault, I am sure, does not rest with your ministry only, but with all the ministries. If and when these delays are brought to your notice about any ministry, please let me know so that I might ginger them up.”

On the same day, Nehru wrote to Azad, drawing the attention of the senior Congress leader to Chetty’s comments, suggesting that Azad look at the possibility of appointing a financial officer in his ministry. “I think this is a good proposal and will expedite work.”

Another row is visible in a series of exchanges between Chetty, Nehru, commerce minister KC Neogy and communications minister Rafi Ahmad Kidwai. This was on Kidwai’s suggestion that the government create a super department to handle income-tax evaders. On March 30, 1948, Kdiwai wrote to Neogy suggesting I-T officers be vested with “certain powers to seize and examine the account books not only of the firm under investigation but also of all those whom they may consider to be involved in the transactions of the firm.” Though the Investigation Commission already had the power, Kidwai argued if the government were to depend on the Commission “it will take years and years to handle the cases already referred to it.”

“I am afraid the problem is more serious than we had contemplated. It is true it contains the names of many prominent industrialists and some well known commercial firms, but there are thousands of cases of persons comparatively unknown but who had cheated the Government to the extent of some crores,” Kidwai says.

A month later, Nehru writes to Neogy reminding him of Kidwai’s letter. “This letter of his contains specific information about certain persons who apparently were defrauding the public exchequer. May I know what is being done in this matter,” Nehru asks Neogy.

Chetty wrote to Nehru on August 9, 1949, about Kidwai’s proposal: “I am not in favour of a super-department for this purpose.” He draws Nehru’s attention to the shortage of staff in the I-T department and says, “It was only last year that 200 new officers were recruited and are under training, which was partly interrupted due to the troubles arising out of the partition of the country.”

Two days latter, on August 11, Kidwai wrote to Chetty telling him the PM has sent him Chetty’s letters. “I was rather surprised you had made no mention of these proposals in either of the two letters I received from you last week. I am not surprised that you do not approve the proposals.”

Kidwai then points out that the Investigation Commission has been given 150 names of tax evaders and more than 5,000 cases, and it has to function like a judicial body. All this means “the Commission will take 15 years or more to complete investigations.” Kidwai sums up his two-page letter, telling Chetty that he was “sending a copy of this letter to the prime minister for his information.”

Red tape rules, then as now.

j_josy@dnaindia.net

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Kind man assists duck family in crossing the road, internet lauds him

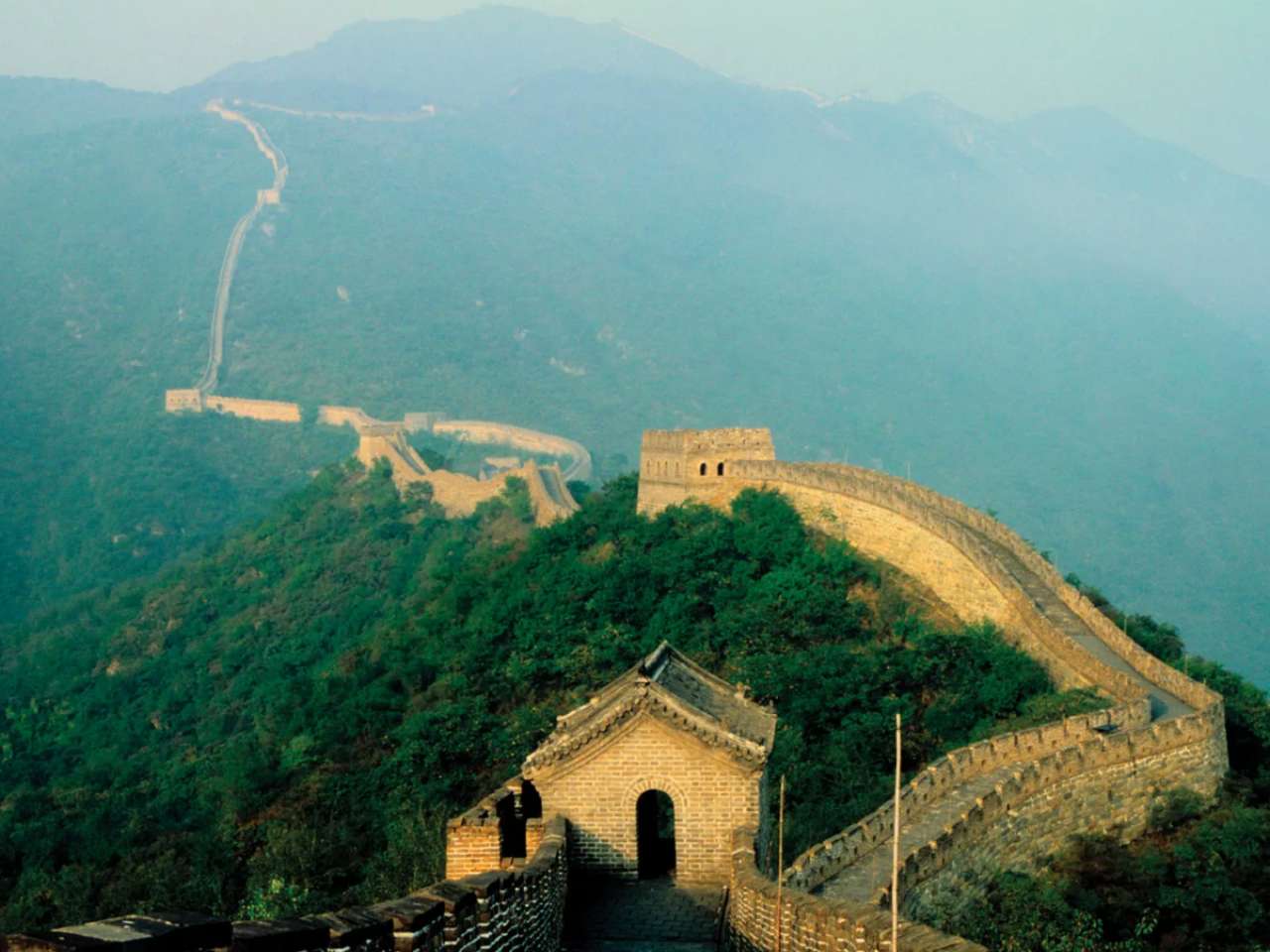

Viral video: Kind man assists duck family in crossing the road, internet lauds him![submenu-img]() Can you see the Great Wall of China from space? here's the truth

Can you see the Great Wall of China from space? here's the truth![submenu-img]() Ashutosh Rana breaks silence on his deepfake video supporting a political party: 'I would only be answerable to...'

Ashutosh Rana breaks silence on his deepfake video supporting a political party: 'I would only be answerable to...'![submenu-img]() Meet India's most talented superstar, is actor, dancer, stuntman, singer, lyricist; not Ranbir, Shah Rukh, Aamir, Salman

Meet India's most talented superstar, is actor, dancer, stuntman, singer, lyricist; not Ranbir, Shah Rukh, Aamir, Salman![submenu-img]() This flop film was headlined by star kid, marked south actress's Bollywood debut, made in Rs 120 crore, earned just...

This flop film was headlined by star kid, marked south actress's Bollywood debut, made in Rs 120 crore, earned just...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, Sonali Bendre celebrate 25 years of Sarfarosh, attend film's special screening

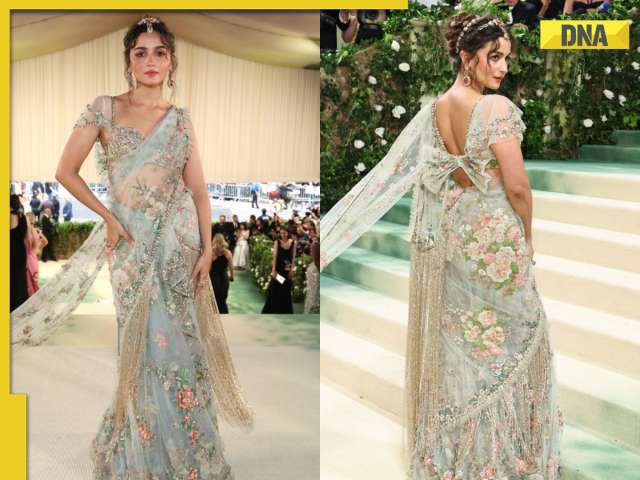

Aamir Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, Sonali Bendre celebrate 25 years of Sarfarosh, attend film's special screening![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Ashutosh Rana breaks silence on his deepfake video supporting a political party: 'I would only be answerable to...'

Ashutosh Rana breaks silence on his deepfake video supporting a political party: 'I would only be answerable to...'![submenu-img]() Meet India's most talented superstar, is actor, dancer, stuntman, singer, lyricist; not Ranbir, Shah Rukh, Aamir, Salman

Meet India's most talented superstar, is actor, dancer, stuntman, singer, lyricist; not Ranbir, Shah Rukh, Aamir, Salman![submenu-img]() This flop film was headlined by star kid, marked south actress's Bollywood debut, made in Rs 120 crore, earned just...

This flop film was headlined by star kid, marked south actress's Bollywood debut, made in Rs 120 crore, earned just...![submenu-img]() India's most successful star kid was superstar at 14, daughter of tawaif, affair with married star broke her, died at...

India's most successful star kid was superstar at 14, daughter of tawaif, affair with married star broke her, died at...![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop actor, worked with superstars, married girl half his age, once left Aamir's film midway due to..

India's biggest flop actor, worked with superstars, married girl half his age, once left Aamir's film midway due to..![submenu-img]() England pace legend James Anderson set to retire from Test cricket after talks with Brendon McCullum

England pace legend James Anderson set to retire from Test cricket after talks with Brendon McCullum![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Shubman Gill, Sai Sudharsan centuries guide Gujarat Titans to 35-run win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: Shubman Gill, Sai Sudharsan centuries guide Gujarat Titans to 35-run win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() KKR vs MI IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs MI IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() 'It's ego-driven...': Ex-RCB star on Hardik Pandya's captaincy in IPL 2024

'It's ego-driven...': Ex-RCB star on Hardik Pandya's captaincy in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() BCCI to advertise for Team India's new head coach after T20 World Cup

BCCI to advertise for Team India's new head coach after T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() Viral video: Kind man assists duck family in crossing the road, internet lauds him

Viral video: Kind man assists duck family in crossing the road, internet lauds him![submenu-img]() Can you see the Great Wall of China from space? here's the truth

Can you see the Great Wall of China from space? here's the truth![submenu-img]() Mother bear teaches cubs how to cross a road with caution, video goes viral

Mother bear teaches cubs how to cross a road with caution, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Meet the tawaif, real courtesan of Heeramandi, was once highest paid item girl, was killed by....

Meet the tawaif, real courtesan of Heeramandi, was once highest paid item girl, was killed by....![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani’s old image with billionaire friends go viral, Harsh Goenka makes joke of…

Mukesh Ambani’s old image with billionaire friends go viral, Harsh Goenka makes joke of…

)

)

)

)

)

)