What if, instead of translating your ideas into actions, you get caught in a web of worry? DNA meets people who overcame obsessions that were dragging them down, and took charge of their lives.

Two years ago, at the age of 30, Sophie, a fashion model, wondered where her old exuberant self was disappearing. Restlessness and anxiety struck almost every day, and her mood swings affected the limited modelling assignments she bagged.

In 2007, armed with a masters degree in history, Sravasti Datta was all set to do her masters in philosophy, but something didn’t feel right. After working for two years post her double MA, Datta had this nagging feeling that she wasn’t being honest with herself.

For Anshul Kaushik, a regular day began with him tiptoeing to the bathroom and taking swigs out of a ‘water bottle’ that actually contained alcohol. When his wife wasn’t looking, he sneaked the bottle to work. When a colleague found out about it, Kaushik was “ashamed and terrified that this would be the end of my job”. But fear wasn’t enough to wean Kaushik off the habit.

There are only a few of us who haven’t — at some point — dawdled, wanting to achieve something but lacking the determination to try. But what if the phase slowly became a way of life itself? What if, instead of finding solutions, one just keeps obsessing about the present, doing little about the future?

For Sophie, Datta and Kaushik, it seemed impossible that things could get better. But they tried to find reasons for their limbo and rise above it.

Vicious circle

It wasn’t easy. Sophie, for instance, had trouble adjusting with her mother-in-law and felt her husband extended little support. “The more I clung on, the more elusive he got. So I decided to focus on my modelling instead. Every day, I’d wake up and plan to push my portfolio aggressively, but as the day wore on, I found myself procrastinating.”

Sophie’s lethargy kept her from getting ‘meaningful’ work. In turn, the lack of work affected her confidence. “Instead of going out and meeting people, I started badgering my friends and my husband for attention. If a friend didn’t return my calls, I saw it as a sign of rejection.”

She could see that the issue wouldn’t just disappear. “It’s one thing to know that you have a problem and quite another to go digging deeper.” It was after a year of worry and no action that Sophie decided to see a psychotherapist. On the couch, she remembered how one of her friends had turned to chanting as a matter of discipline and wondered whether she should give it a shot.

Finding answers

Datta, too, realised she had to do something about her niggling doubts and joined the Indian branch of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI).

Sessions of chanting and speaking to members helped her realise that she was grossly avoiding her real interest — journalism. Throughout her childhood, Datta had wondered what it must be like to be a journalist, to be able to meet interesting people and tell their stories, and contribute to society. But as she studied history, which she considered ‘prestigious’ then, she realised she was simply going down the beaten track.

“I was always worried whether I would be able to perform well,” she explains. “Soon, I realised that I wasn’t being true to myself. I was hesitant to venture outside my comfort zone, but I realised that it is cowardice to sit around, waiting for things to happen to me.”

But after sessions with SGI members, she worked up the courage to apply to media organisations. Happily, two months ago, she

was hired as a reporter by a reputed national daily.

Sophie too realised something about her had to change — for good. After chanting and counselling, she wondered whether she was simply too used to having people at her beck and call. She probably expected them to lift her mood — the way her family had done when she was younger. “I had supportive friends, but I wanted more attention. I didn’t want the responsibility of looking after myself.”

Gradually, whenever Sophie felt the urge to call her friends, she forced herself to chant until she got calmer. That also helped her find modelling assignments she was interested in, and she accepted that her shelf-life was limited. Her relationship with her husband improved because she learned to respect his space. Sophie is now contemplating assisting a friend at a boutique — to have a plan of action at all times.

Just not good enough

For Kaushik, it took longer to realise he had a problem. He couldn’t control drinking at work, even after his boss issued him a warning. “The lowest blow came when I overheard my son tell my wife that he didn’t want to call his friends over because I stank of alcohol.”

Kaushik’s wife realised they weren’t going to be able to control his addiction without external help. After vehemently denying it, he finally accepted that his ‘social drinking’ had gone way out of control and that he needed help. “I constantly ran myself down thinking I wasn’t a good husband and father. I turned to alcohol so I could escape these thoughts. Yoga and counselling helped me take things one day at a time,” says Kaushik.

Sophie agrees. “Today when I look back, I realise it was easier to sit and weave ideas about what I expected from life. The hard part was accepting that without action, ideas are worth nothing.”

![submenu-img]() This singer left Air Force, sang at churches, became superstar; later his father killed him after...

This singer left Air Force, sang at churches, became superstar; later his father killed him after...![submenu-img]() Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...

Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...![submenu-img]() Anil Ambani’s Rs 96500000000 Reliance deal still waiting for green signal? IRDAI nod awaited as deadline nears

Anil Ambani’s Rs 96500000000 Reliance deal still waiting for green signal? IRDAI nod awaited as deadline nears![submenu-img]() Most popular Indian song ever on Spotify has 50 crore streams; it's not Besharam Rang, Pehle Bhi Main, Oo Antava, Naina

Most popular Indian song ever on Spotify has 50 crore streams; it's not Besharam Rang, Pehle Bhi Main, Oo Antava, Naina![submenu-img]() Did Diljit Dosanjh cut his hair for Amar Singh Chamkila? Imtiaz Ali reveals ‘he managed to…’

Did Diljit Dosanjh cut his hair for Amar Singh Chamkila? Imtiaz Ali reveals ‘he managed to…’ ![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

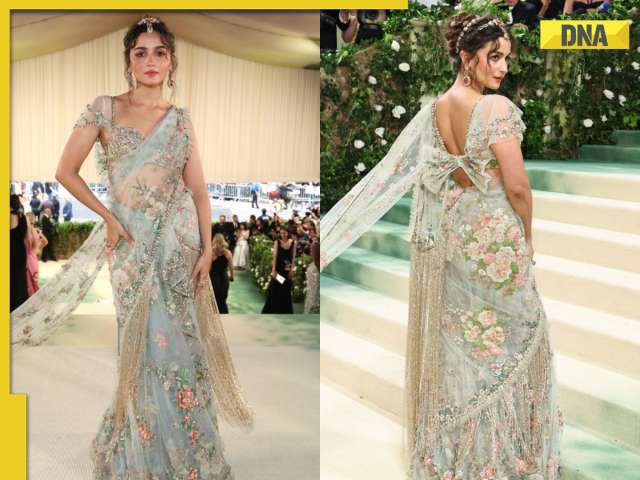

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() This singer left Air Force, sang at churches, became superstar; later his father killed him after...

This singer left Air Force, sang at churches, became superstar; later his father killed him after...![submenu-img]() Most popular Indian song ever on Spotify has 50 crore streams; it's not Besharam Rang, Pehle Bhi Main, Oo Antava, Naina

Most popular Indian song ever on Spotify has 50 crore streams; it's not Besharam Rang, Pehle Bhi Main, Oo Antava, Naina![submenu-img]() Did Diljit Dosanjh cut his hair for Amar Singh Chamkila? Imtiaz Ali reveals ‘he managed to…’

Did Diljit Dosanjh cut his hair for Amar Singh Chamkila? Imtiaz Ali reveals ‘he managed to…’ ![submenu-img]() Watch: Arti Singh gets grand welcome at husband Dipak's house with fairy lights and fireworks, video goes viral

Watch: Arti Singh gets grand welcome at husband Dipak's house with fairy lights and fireworks, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who belongs to family of superstars, quit films after 19 flops, no single hit in 9 years; is still worth…

Meet actress, who belongs to family of superstars, quit films after 19 flops, no single hit in 9 years; is still worth…![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Suryakumar Yadav's century power MI to 7-wicket win over SRH

IPL 2024: Suryakumar Yadav's century power MI to 7-wicket win over SRH![submenu-img]() DC vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Team India’s new jersey for T20 World Cup 2024 unveiled

Watch: Team India’s new jersey for T20 World Cup 2024 unveiled![submenu-img]() DC vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Rajasthan Royals

DC vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Kolkata Knight Riders take top spot after 98 runs win over Lucknow Super Giants

IPL 2024: Kolkata Knight Riders take top spot after 98 runs win over Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...

Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...![submenu-img]() Meet man whose salary was only Rs 83 but his net worth grew by Rs 7010577000000 in 2023, he is Mukesh Ambani's...

Meet man whose salary was only Rs 83 but his net worth grew by Rs 7010577000000 in 2023, he is Mukesh Ambani's...![submenu-img]() Job applicant offers to pay Rs 40000 to Bengaluru startup founder, here's what happened next

Job applicant offers to pay Rs 40000 to Bengaluru startup founder, here's what happened next![submenu-img]() Viral video: Family fearlessly conducts puja with live black cobra, internet reacts

Viral video: Family fearlessly conducts puja with live black cobra, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Woman demands Rs 50 lakh after receiving chicken instead of paneer

Woman demands Rs 50 lakh after receiving chicken instead of paneer

)

)

)

)

)

)