Call centres are an easy ticket to upward mobility and financial stability for many women.

Call centres are an easy ticket to upward mobility and financial stability for many women. But the stereotypes and stigmas that come with the job can make it a tough trade-off. Taran N Khan reports on the grey spots behind the bright lights

Shameen Lakhani, a BPO worker, is unhappy with her sister’s suitors. “Some people had come to see her one day,” she recalls. “When they heard she works in a call centre, their expressions changed. You could see them thinking, what does she do outside the house all night?” Even as generous salaries boost their financial status, the matrimonial stock of women working in BPOs appears to have taken a plunge.

The graveyard shifts worked by prospective brides as well as the aura of licentiousness around the industry has caused many a marriage negotiation to fall apart. Fear of being tarred with the fatal call centre tint has prompted 20-year-old Nidhi to assume a dual identity. “My parents are very traditional. They have allowed me to work, but we haven’t told my aunts or grandparents,” she says. “If people get to know, they talk.” Faced with stereotypes and stigma, BPO women employees are trying to find a voice in the burgeoning yet infant industry.

Increasingly, single girls are using these jobs as lucrative stopgaps, saving between Rs 3-4 lakhs in the years before they get married and quit. “The money is a big draw,” admits Tripti Das, programme manager. “Now, even if I want to leave, I have to think twice because it means making less money than I am used to.”

“I have a friend who lost her father as a child,” says Nimit Saluja, manager. “She has used her BPO earnings to buy a house and arrange for her wedding expenses and dowry, so her family doesn’t have to face any burden.”

BPOs are a feasible career option for married women with families too. For Shireena C, working night shifts means getting to spend the day with her young son. “I tuck him in and leave for work,” she smiles. The arrangement works since her mother runs the house. “If I stayed with my in-laws, I would have many more responsibilities,” she admits.

“Women who have to balance traditional domestic duties with night shifts face a lot more stress,” agrees Gita Naidu, single mother with an adopted daughter. Those who do try to pull it off often end up caught in a blur of sleep-deprived activity, with no time for themselves. “Daylight is a scarce commodity for us. You have to really ration your waking hours and squeeze all your work and life into them,” she says.

Naidu is amused to be part of a sector where the hardcore party animal is something of an industry emblem. “There are kids who have no responsibilities and can spend their entire salaries as pocket money,” she says. “But for people like us who live off our earnings, that’s not an option.”

In fact, good old-fashioned frugality seems to be all the rage even amongst the younger crowd. “I save about half my salary,” says Heena, a tele-marketing agent. The oldest child in a family of six, she joined the BPO industry while still in college. She now commutes between Thane and Malad every night, helping her tailor father with the household expenses. Similarly, Nidhi has taken on the responsibility of paying the school fees of her three younger siblings. Both the girls are the first generation of women to work outside the home.

“Call centres represent a window of opportunity for that section of women who would otherwise have remained homebound or been married off at the first chance,” observes Vinod Shetty, lawyer, who runs a support group for call centre workers. He also points to the influx from small towns, with girls living in often squalid conditions in the city so they can send money back home. “Where else will they get the opportunity to break out of domestic routine and have a life of their own?” he asks.

But once inside these towers of nocturnal activity, women are often put in a corner. Shetty recalls a Delhi-based worker who was fired because she got pregnant. “She even offered to terminate her pregnancy, but was still asked to leave.” Sexual harassment on the phone as well as work remains a problem. “My boss called me to his office, ostensibly to talk about my promotion,” recalls Karen D’Souza, a former trainer. “There, he put a hand on my thigh and suggested "to get something you have to give something”. D’Souza has since taken legal action against the company, aided by Shetty’s Young Professionals’ Collective.

“Women are expected to be ‘good sports’ and ‘take a joke’. If a girl is reserved and doesn’t enjoy open interaction with men, she is often targeted and bullied,” feels Shetty. “This is a more subtle but disturbing form of harassment common in call centres.”

On the upside, say women, the management is usually open to redressing problems, partly because of strict guidelines in the parent companies located abroad. “Since the murder (of Pratibha) in Bangalore, our security has been beefed up,” says Lakhani.

What rankles the most is the lack of respect her job carries. “Even doctors or airlines staff work at night, but this is not considered a real job.” Saluja, however, is dismissive of the raised eyebrows. “I’m only 23 but I’ve bought a house for my family. Whatever people say, I feel very proud of myself,” she declares. For Heena, her call centre job is an opportunity to reduce her father’s financial worries. “He should never regret having a daughter,” she says. “I want to be as good as a son to him.”

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy

Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy![submenu-img]() RCB cancels practice, press meet after threat to Virat Kohli's security ahead of IPL 2024 eliminator: Report

RCB cancels practice, press meet after threat to Virat Kohli's security ahead of IPL 2024 eliminator: Report ![submenu-img]() Meet Indian-origin man, IIT alumnus who is world's second-highest paid CEO, his salary per day is...

Meet Indian-origin man, IIT alumnus who is world's second-highest paid CEO, his salary per day is...![submenu-img]() RBI approves Rs 2.11 lakh crore dividend payout to Indian govt for 2023-24

RBI approves Rs 2.11 lakh crore dividend payout to Indian govt for 2023-24![submenu-img]() Mozz Guard Mosquito Zapper Reviews (Zap Guardian): Side effects, ingredients benefits, price

Mozz Guard Mosquito Zapper Reviews (Zap Guardian): Side effects, ingredients benefits, price![submenu-img]() IIT graduate builds Rs 1057990000000 company, leaves to get a job, now working as a….

IIT graduate builds Rs 1057990000000 company, leaves to get a job, now working as a….![submenu-img]() Indian Air Force Agniveervayu Recruitment 2024: Registration starts today, know eligibility, steps to apply

Indian Air Force Agniveervayu Recruitment 2024: Registration starts today, know eligibility, steps to apply![submenu-img]() Meet woman who was married at 16, faced domestic abuse, did odd jobs as single mom, became IAS officer, is posted at...

Meet woman who was married at 16, faced domestic abuse, did odd jobs as single mom, became IAS officer, is posted at...![submenu-img]() Maharashtra HSC 12th 2024: Result declared, know how to check

Maharashtra HSC 12th 2024: Result declared, know how to check![submenu-img]() Meet man who topped IIT-JEE, studied at IIT Bombay, then went to MIT, now is...

Meet man who topped IIT-JEE, studied at IIT Bombay, then went to MIT, now is...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer

AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer![submenu-img]() Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet

Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024

Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'

Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'![submenu-img]() Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024

Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() Watch: Kapil Sharma's daughter complains as paps click her photos in viral video, says 'papa aapne kaha tha ki...'

Watch: Kapil Sharma's daughter complains as paps click her photos in viral video, says 'papa aapne kaha tha ki...'![submenu-img]() Watch: Anil Kapoor hijacks The Great Indian Kapil Show, Farah Khan reveals which actor is 'most kanjoos' in Bollywood

Watch: Anil Kapoor hijacks The Great Indian Kapil Show, Farah Khan reveals which actor is 'most kanjoos' in Bollywood![submenu-img]() Manoj Bajpayee reveals why Anurag Kashyap didn’t work with him for 14 years: ‘My career was going down, he didn’t...'

Manoj Bajpayee reveals why Anurag Kashyap didn’t work with him for 14 years: ‘My career was going down, he didn’t...'![submenu-img]() Sanjay Dutt quits Welcome 3 after fallout with Akshay Kumar? Report says he walked out after first day because...

Sanjay Dutt quits Welcome 3 after fallout with Akshay Kumar? Report says he walked out after first day because...![submenu-img]() Allu Arjun enjoys lunch with wife Sneha at dhaba; fans hail his ‘simplicity’ despite Pushpa success

Allu Arjun enjoys lunch with wife Sneha at dhaba; fans hail his ‘simplicity’ despite Pushpa success![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy

Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy![submenu-img]() Groom saves bride from unexpected milk bath during haldi ceremony, viral video melts internet

Groom saves bride from unexpected milk bath during haldi ceremony, viral video melts internet![submenu-img]() Viral video captures epic showdown between two king cobras, watch who wins

Viral video captures epic showdown between two king cobras, watch who wins![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman's 'Senorita' dance steals hearts during RCB vs CSK match in Bengaluru, watch

Viral video: Woman's 'Senorita' dance steals hearts during RCB vs CSK match in Bengaluru, watch ![submenu-img]() Viral video: Lion's terrifying ambush on napping wildebeest stuns internet, watch

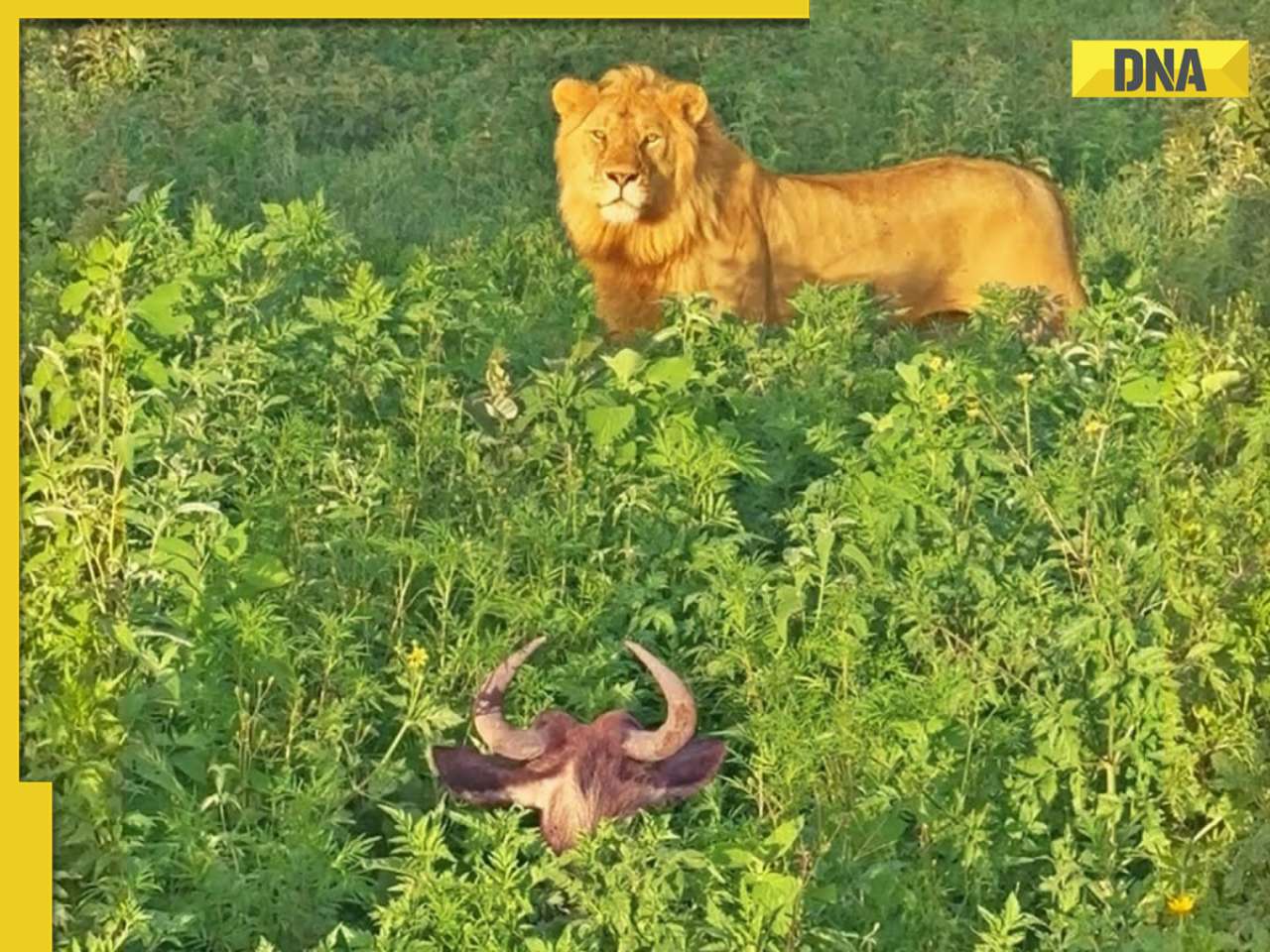

Viral video: Lion's terrifying ambush on napping wildebeest stuns internet, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)