A chef is the controlling hand behind most of our lives’ special occasions. Food is the epicentre of celebration, spinning on their expertise and efficiency in the kitchen — a late or over spiced meal can ruin the most celebratory dinner, the perfect wedding buffet marks the foundation for the extended family’s benevolent blessings, or a simple dal and roti bring back sharp memories of home and childhood.

Contrasting their culinary creations with their infantry-like training is a jolt to the perception of the chef as a jolly artist. On his first day at work, Nirmal Monteiro was exhausted and in pain, after standing and working all day in a hot and busy kitchen. He remembers his head chef who would send him trotting to the pantry every time he had to mix his secret spices. It took Monteiro two hours to manually grind garam masala with a hamam dasta, after which the head chef would carry the spices home at night to keep them safe.

This day was followed by ten years of such days; working seven days a week, 365 days a year for other people’s weddings and birthdays. Monteiro travelled from Andheri to Cuffe Parade everyday, his day starting at 10am and ending around 2am. It was the best of years; it was the worst of years. Thirty years later, now the executive chef for multiple eateries around the city, Monteiro talks fondly of those gruelling years, calling them the best of his long and illustrious career, saying, “The pure enjoyment of cooking, how relaxing and invigorating it is — can’t be described.”

Celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain, much adored by the public and scoffed at by most of the haute cuisine establishment, says in his book — “We’re unlovable. That’s why we’re chefs. We’re basically bad people…proudly dysfunctional. Which is why we lived the way we did, this half-life of work followed by hanging out with others who lived the same life…we are misfits, and this is all we know how to do.” The chef works rapidly, efficiently and silently, usually only called out on the rare occasion when his food misses its mark. They work a minimum of twelve hours a day in difficult conditions — it’s surprising that so many of us now aspire to be one of them. With a surfeit of cooking shows as well as the anticipated launch of two food channels — one inexplicably named Food Food — everyone’s suddenly a chef.

But what qualities maketh the Master Chef? “You can’t be a master ‘chef’ by appearing on television, no matter what Akshay Kumar says,” apprentice chef Dilip Mansingh says bluntly. Mansingh admits though, there are certain recipes you should have perfected before calling yourself a chef — “Making the perfect dal. Making a well-cooked steak is important. Know how to improvise and change your recipe according to requirements.” Chef Joy Bhattacharya, executive chef at the Trident, says that what you see on television is the “outer shell” of a chef’s life, though it provides a “terrific platform” for the joys of cooking.

Chef Paul Kinny, executive chef, Intercontinental, Marine Drive confirms Bourdain’s foreboding about the ‘unlovable’ chefs — “Chefs are very, very temperamental. It’s a hot and uncomfortable environment and very high-pressure. There is no scope to make a mistake. And besides, they’re very creative people. You can’t tell an artist what to do without expecting some fireworks.”

At the back of the kitchen, everything is always an emergency. “People are screaming and shouting, and getting hurt. If you think you’re going to wear a nice hat and stand in the corner, please think twice about turning your hobby into a profession.” But chef Kinny says he wouldn’t give it up for the world, having returned to the kitchen after a stint on the corporate side. “I always tell my friends, if I wasn’t a chef, I would be a dead chef,” he laughs. “The high of a busy kitchen is different from any other experience.”

“Patience is not a virtue in this field,” says chef Ananda Solomon, the executive chef at the Taj President. “There is no time to think. If you miss the train someone else will get there before you.” Solomon talks briskly about building a “brand”, understanding its value, its audience and their expectations. “I’m aware that what I make isn’t the Eiffel Tower,” he says. “It has a short life, and will disappear in a couple of minutes. It will be eaten, enjoyed, and then it is history and I start again. What chefs make are ultimately memories.”

![submenu-img]() House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins

House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins![submenu-img]() Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle

Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle![submenu-img]() Apple partners up with Google against unwanted tracker, users will be alerted if…

Apple partners up with Google against unwanted tracker, users will be alerted if…![submenu-img]() Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..

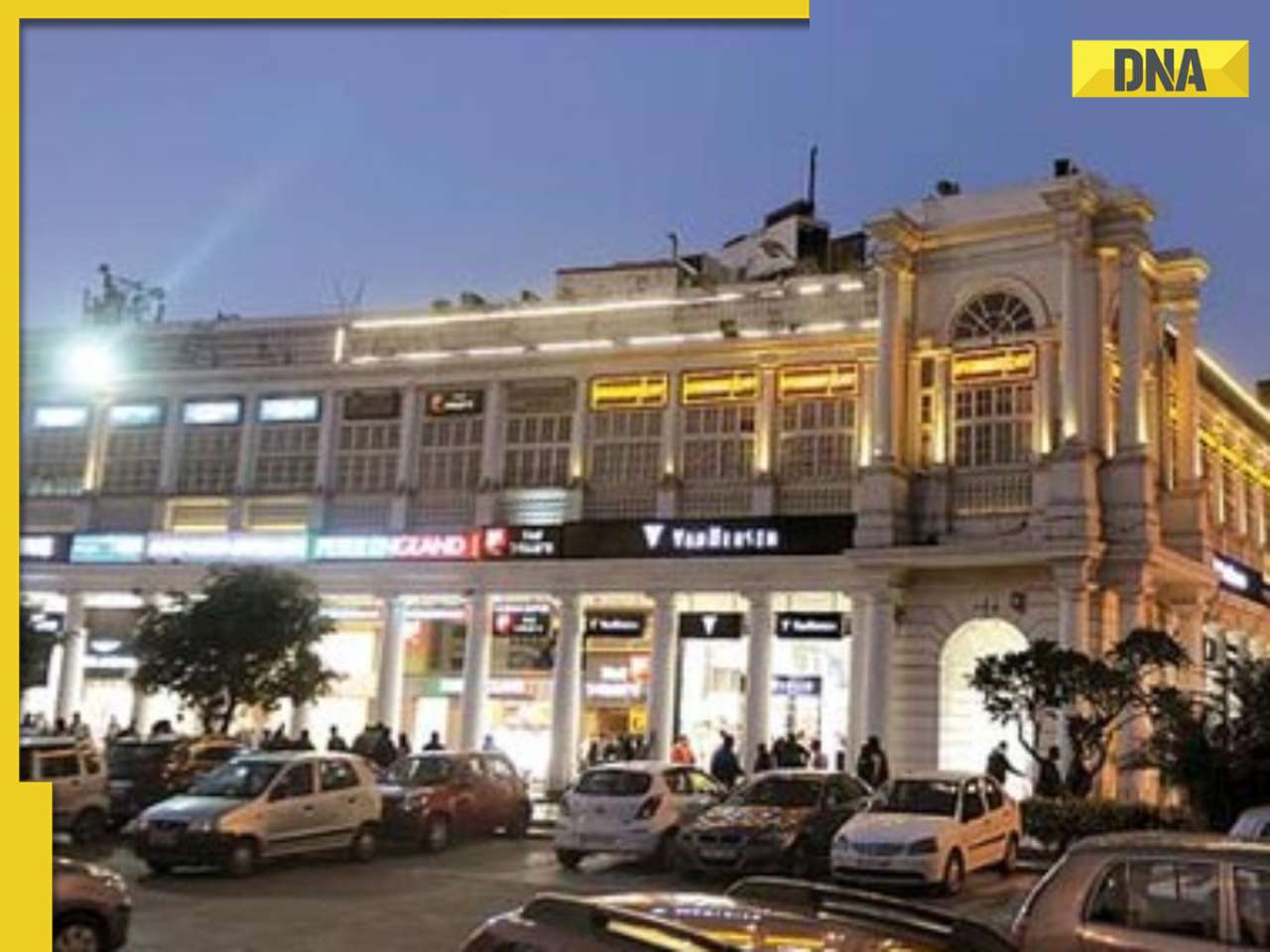

Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..![submenu-img]() Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?

Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?![submenu-img]() Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...

Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…

IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…![submenu-img]() Goa Board SSC Result 2024: GBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here

Goa Board SSC Result 2024: GBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here![submenu-img]() CUET-UG 2024 scheduled for tomorrow postponed for Delhi centres; check new exam date here

CUET-UG 2024 scheduled for tomorrow postponed for Delhi centres; check new exam date here![submenu-img]() Meet man who lost eyesight at 8, bagged record-breaking job package at Microsoft, not from IIT, NIT, VIT, his salary is…

Meet man who lost eyesight at 8, bagged record-breaking job package at Microsoft, not from IIT, NIT, VIT, his salary is…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'

Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins

House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins![submenu-img]() Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle

Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle![submenu-img]() Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..

Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..![submenu-img]() 'Ek actress 9 log saath leke...': Farah Khan criticises entourage culture in Bollywood

'Ek actress 9 log saath leke...': Farah Khan criticises entourage culture in Bollywood![submenu-img]() Bollywood’s 1st multi-starrer had 8 stars, makers were told not to cast Kapoors; not Sholay, Nagin, Shaan, Jaani Dushman

Bollywood’s 1st multi-starrer had 8 stars, makers were told not to cast Kapoors; not Sholay, Nagin, Shaan, Jaani Dushman![submenu-img]() Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?

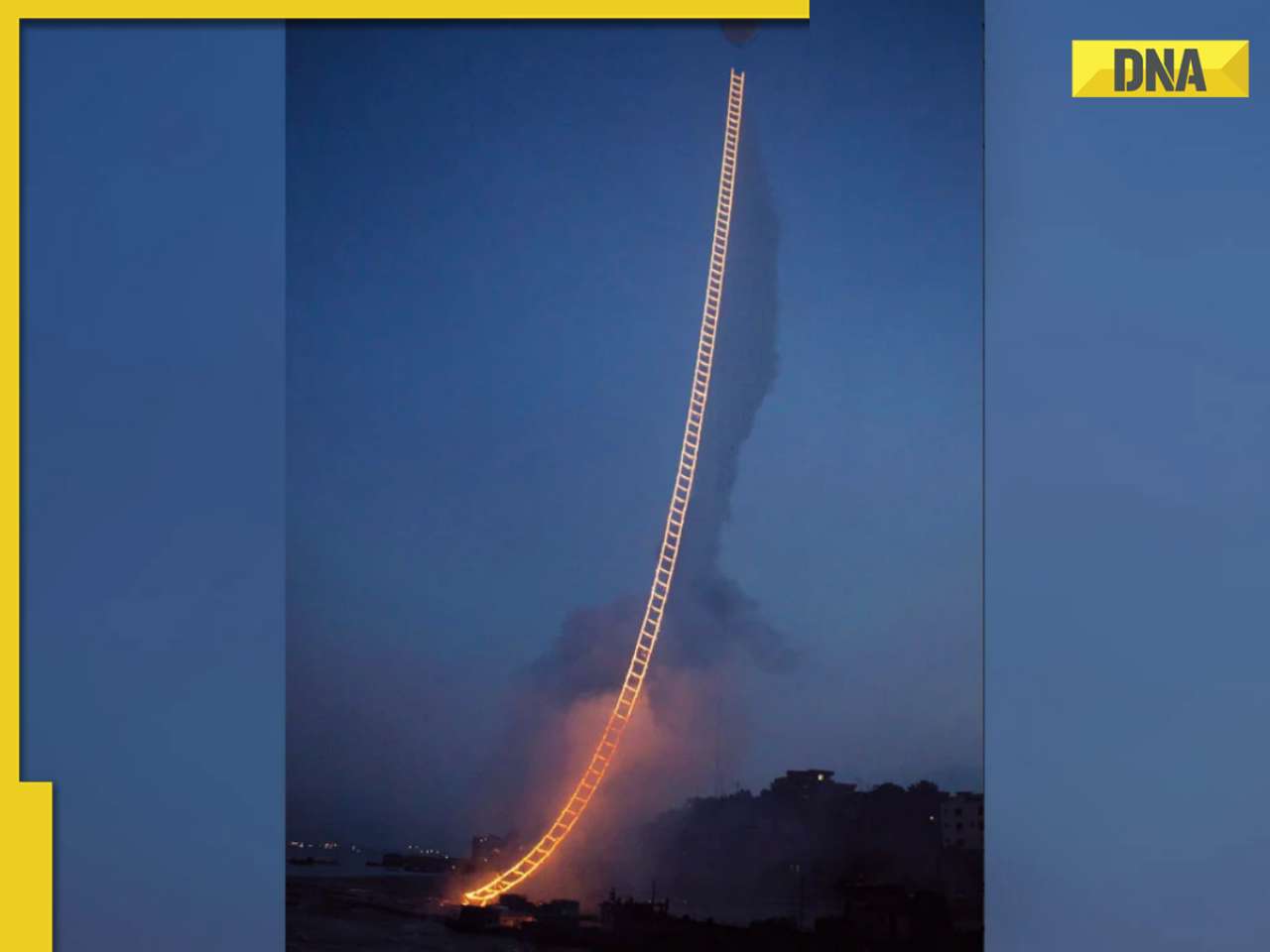

Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?![submenu-img]() Viral video: Chinese artist's flaming 'stairway to heaven' stuns internet, watch

Viral video: Chinese artist's flaming 'stairway to heaven' stuns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: White House plays 'Sare Jahan Se Achha Hindustan Hamara" at AANHPI heritage month celebration

Video: White House plays 'Sare Jahan Se Achha Hindustan Hamara" at AANHPI heritage month celebration![submenu-img]() Viral video: Bear rides motorcycle sidecar in Russia, internet is stunned

Viral video: Bear rides motorcycle sidecar in Russia, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Driver caught on camera running over female toll plaza staff on Delhi-Meerut expressway, watch video

Driver caught on camera running over female toll plaza staff on Delhi-Meerut expressway, watch video

)

)

)

)

)

)