India is in a sweet spot of growth but the only problem is fast-paced growth makes its own demands and the question is whether India can rise to the challenge.

NEW DELHI: Four months before the Central Statistical Organisation put out figures showing gross domestic product (GDP) had grown 8.1% in the first half of 2005-06, economist Surjit S Bhalla was making a presentation on Indian Economy: Breaking Away at the Aspen Institute Programme on the World Economy. ”India is in a sweet spot of growth and this can last another decade or two,” one of his slides said.

Sure it can, is the general consensus, despite some downside risks - the slowing down of the world economy, and rising oil prices, to name just two. The only problem is fast-paced growth makes its own demands and the question is whether India can rise to the challenge.

An expanding economy - and a growing industry - will have a huge appetite for fuel - whether it is petroleum or coal or gas. “Energy demand usually grows as fast as GDP and there is a need to ensure that energy supplies keep pace with growing industrialisation,” says Ajit Ranade, group chief economist, Aditya Birla Management Corporation.

Indian industry isn’t as huge a guzzler of oil as many other countries - oil intensity (use of oil per unit of output) has actually fallen a bit since 2000 when it was 0.05 to 0.04 now. But this could well change and, with close to 70% of oil requirements being imported, this could push up India’s oil import bill. And if the currently softer international oil prices start to harden again, it could change the outlook for the economy. A study by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Ficci) — “Impact of high oil prices on Indian economy” — quotes the International Energy Agency as observing that a $10 per barrel increase in oil prices would reduce India’s GDP growth by 1%. The Ficci study shows that the negative impact of oil prices is higher in India than elsewhere largely because of the high levels of diesel consumed by industry for captive power plants. Among the biggest users of diesel-based captive power plants are the textiles, automobiles and engineering industries (areas where India is very competitive).

That points to the other major challenge - the need to address the issue of power supply (close to 8,000 mw of additions to capacity are estimated to be required). Fuel is an issue here as well. Coal production - though the quality of Indian coal isn’t very good - is currently mired in a slew of policy distortions. Several National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) plants have reached financial closure, but are waiting for gas supplies. Addressing all these issues is just one part of what needs to be done. The other, says DH Pai Panandiker, president, RPG Foundation, is to look for alternative sources of fuel. For him the best option would be nuclear power, since other alternative sources like wind or solar energy can never meet the huge requirements that will come up.

Other infrastructure will also come under strain, especially ports and roads. A growing industry will consume more imports - again pushing up the import bill - and churn out more goods for exports (manufactured goods account for close to 80% of exports). Though turnaround time in ports has improved, that won’t be good enough for the exponential rise in trade which is sure to happen. There is work going on for road and rail connectivity of ports but the pace will have to be stepped up.

The need to act on the infrastructure front would definitely put pressure on public finances. That public investment will have to be stepped up is something that even Bhalla acknowledges. But there’s a classic conundrum here - how to increase public spending while keeping the deficit within manageable limits (something the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act mandates the government to do). In any case, Bhalla notes, a 10 percentage points improvement in the fiscal deficit will add 1% a year growth in GDP.

A high fiscal deficit could also lead to credit getting squeezed, thanks to rising demand. The cost of capital will go up, warns SS Bhandare, advisor, economic and government policy, at the Tata Strategic Management Group, pushing up interest rates. Internationally, too, he points out interest rates seem set to rise, with the European Central Bank and Japan indicating a rise is likely. Not everyone agrees. Credit sources are widening, Ranade points out, with access to external commercial borrowings, deepening of the corporate bond market and initial public offers. Bhalla insists the central bank will never sabotage the industrial recovery by raising interest rates. They will, he is sure, go down over time.

Overall costs could go up as input costs rise, with increasing demand. World commodity prices are already heading north, Ranade notes, and the process could hasten as other economies also start expanding.

![submenu-img]() ‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…

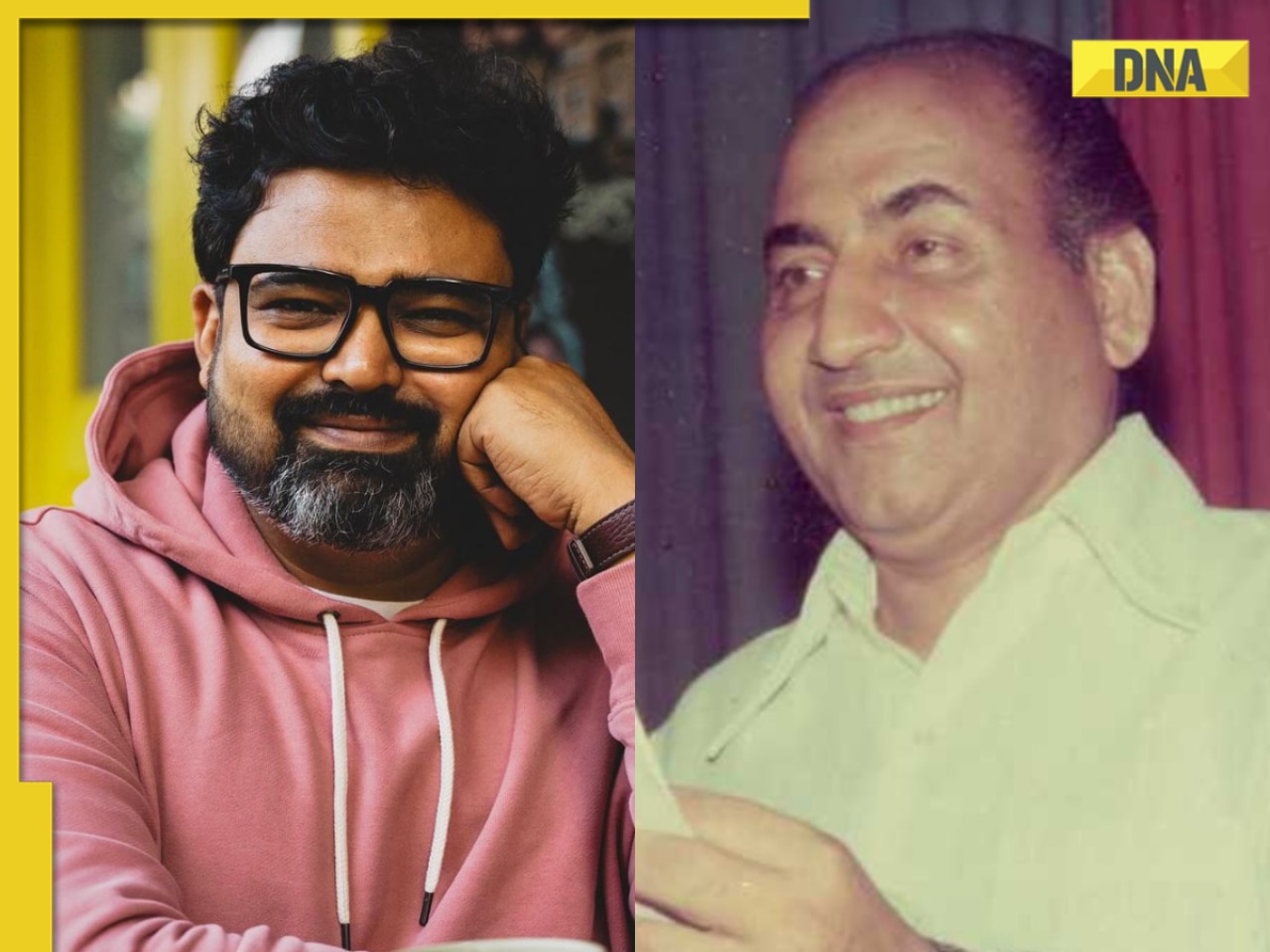

‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

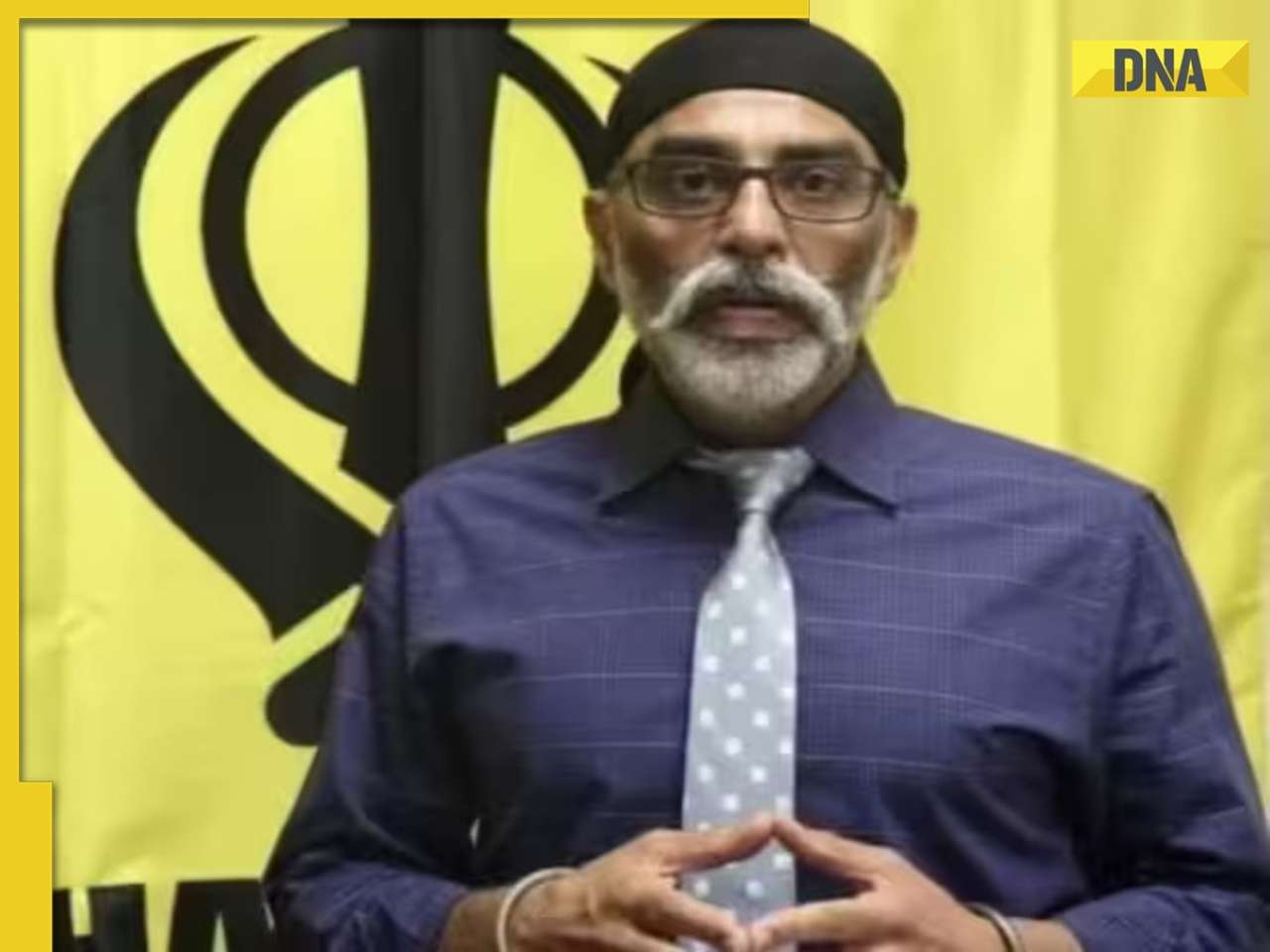

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() 'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot

'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot![submenu-img]() JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy

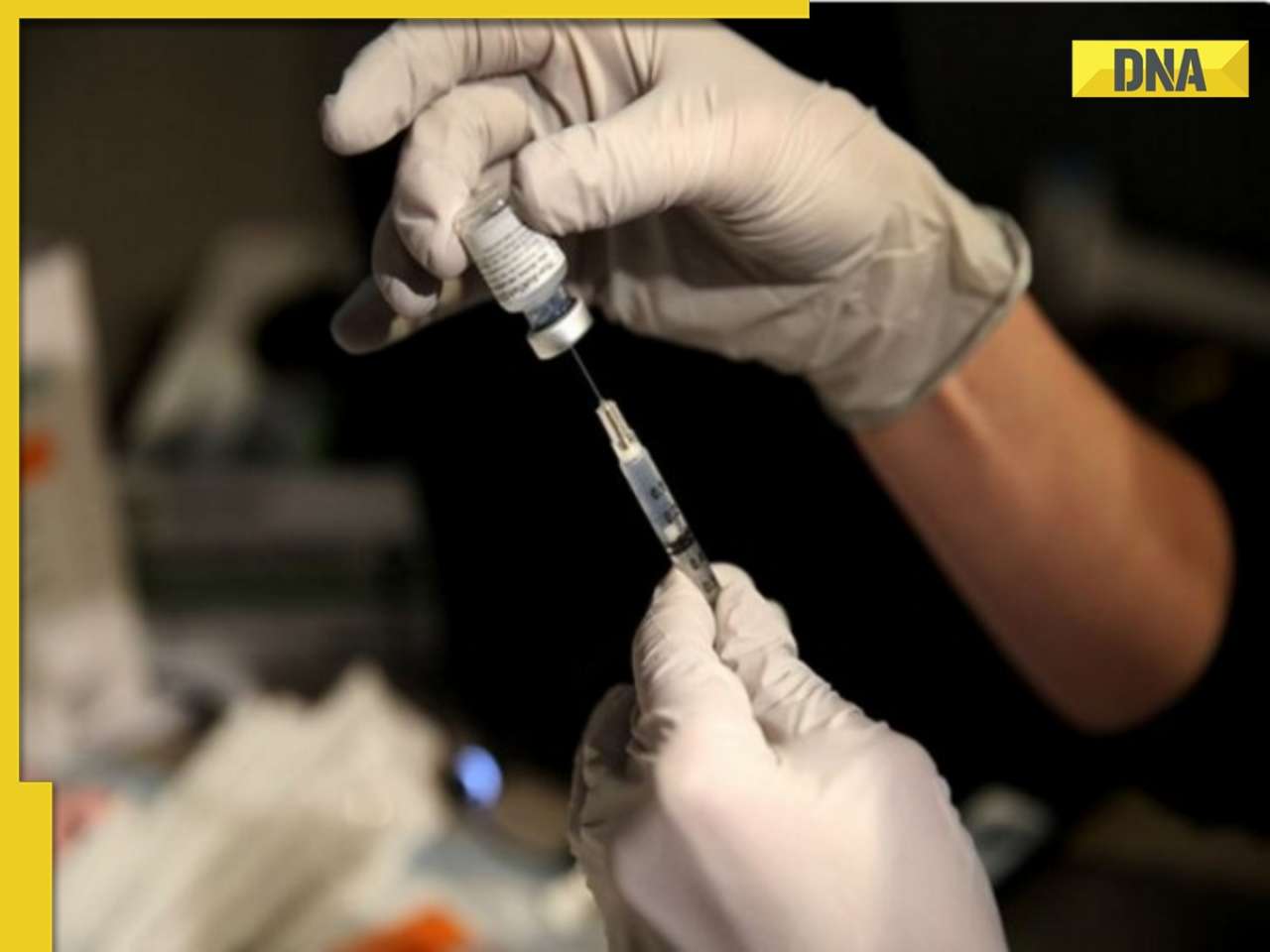

JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy![submenu-img]() AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...

AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’

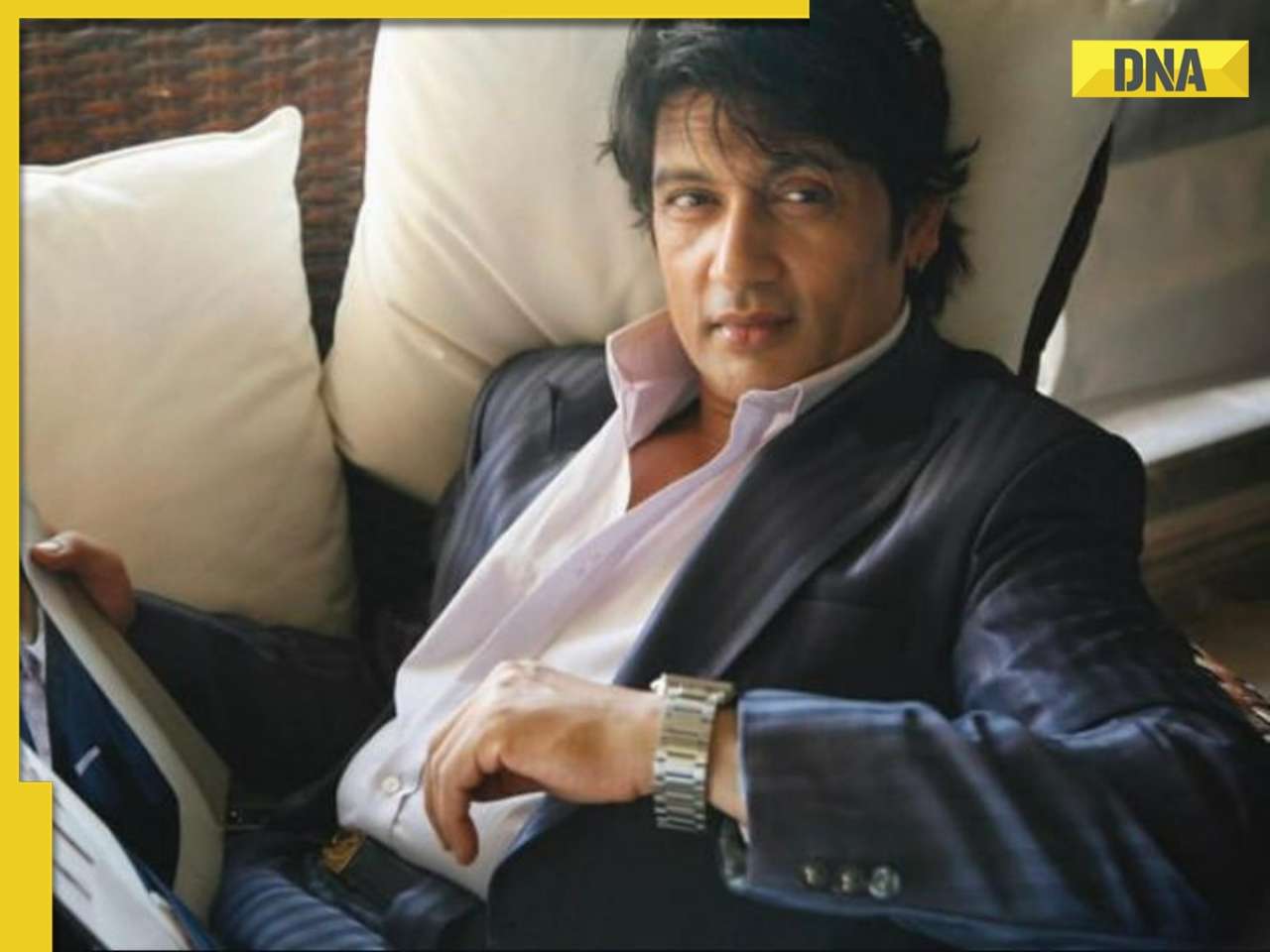

Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’![submenu-img]() Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..

Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore

Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...

Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals

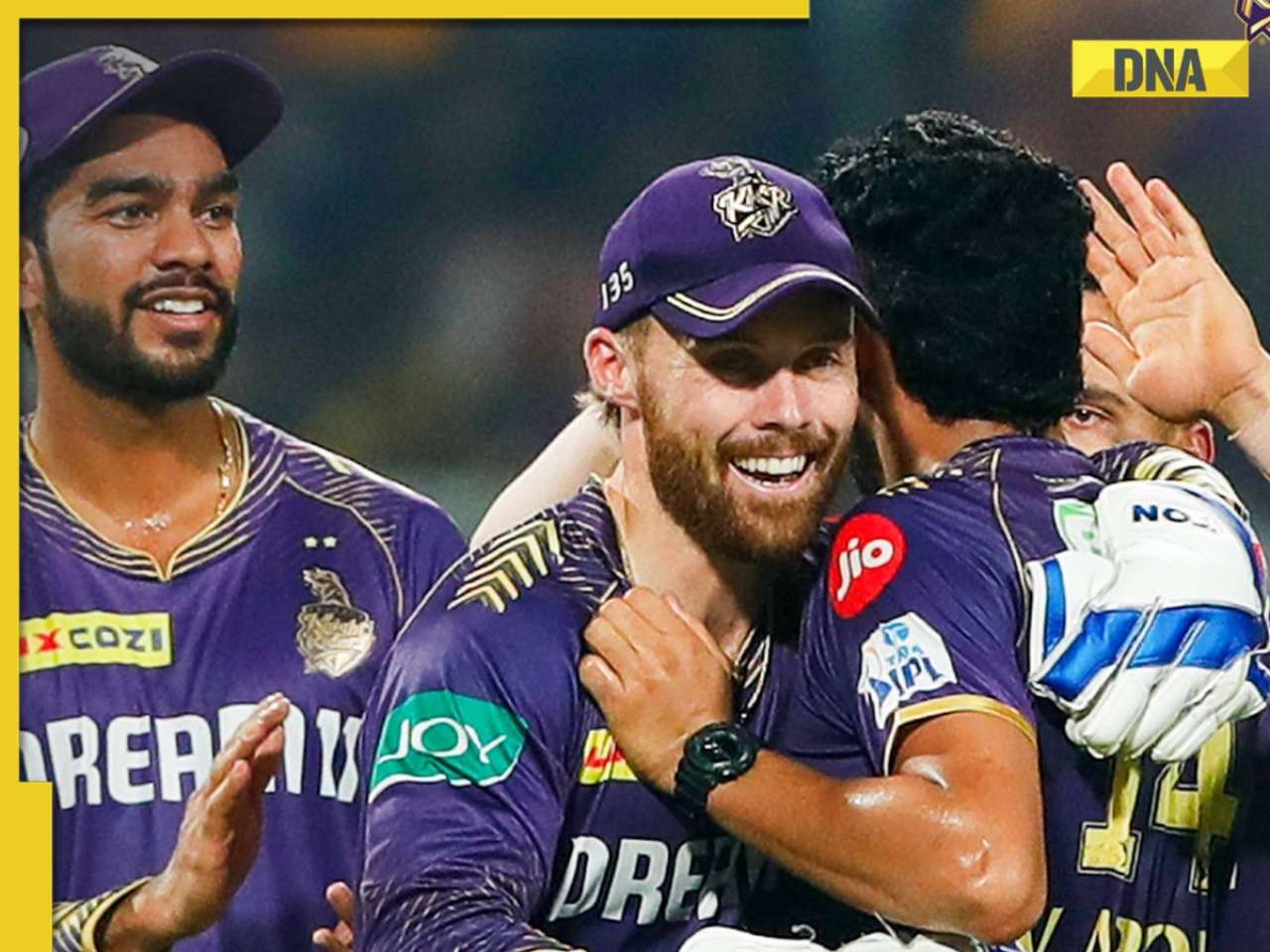

IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket

'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket![submenu-img]() 'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024

'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians

LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)