Australian cartoonist Gavin Aung Than, whose Zen Pencils is one of the most popular web comics, talks to Roshni Nair about his art and a connect that goes beyond the web comic fan space

In February 2012, just 10 days after his pet project had kicked off, Gavin Aung Than posted comic number 10. The first of the three-part 'Poetic Justice Saga' saw William Ernest Henley's Invictus adapted into a graphic story about school bullying. The narrative in related strips – comics 21 and 45 – revolved around Rudyard Kipling's If and Walt Whitman's O Me! O Life!.

For many, the 'Poetic Justice Saga' was the gateway to Than's Zen Pencils, where poems, speeches, stand-up acts and quotes transform into the Australian cartoonist's interpretations of the originals. At 187 cartoons and counting, Zen Pencils, along with Cyanide & Happiness, xkcd and The Oatmeal is one of the most popular web comics ever – one whose reach goes beyond the web comic fan space.

"Many comics cater to specific niches: gaming, geek culture, fantasy. These have a more general appeal and can be enjoyed by people who don't usually read comics," feels Than, when asked why other great web comics don't have a wider appeal. "Also, they also have self-contained strips which are not part of a long, ongoing narrative – which helps reach a wider audience."

Than started Zen Pencils after eight years as a graphic designer in two Australian newspapers. At the time, he had his own syndicated comics, Dan and Pete and Boys Will Be Boys. The demands of a job he's described as "soul-crushing" meant he'd turn to the more democratic, but crowded world of web comics, equipping stock motivation with sucker punches that moisten the eye.

Nowhere is the impact of Than's work felt as greatly as in the silent panels. Take for instance comic 104, on Malala Yousafzai. Handpicking quotes from her blog, an interview and a documentary on her life, he made a cartoon that was as straightforward as they come, but whose 14 of 19 panels were devoid of typography. The hardest-hitting bit: a panel featuring nothing but the teen's fear-stricken eyes and the reflection of the Taliban gunman's weapon in them. Zen Pencils may have been borne of the power of words but its maker relies, more often than not, on the power of silence – most notably in comic 108, where anti-Nazi crusader Sophie Scholl's (disputed) quote, 'The Fire Within', was adapted into a strip on Occupy Wall Street.

But Than doesn't downplay the importance of typography; quite the opposite. "It's very important in comics because it can dictate the flow and pace of the story," he explains. "It's the first thing the reader's eye is drawn to. I have an appreciation for beautiful typography and try to put some thought and effort in it."

So successful is Zen Pencils that its compendiums, Zen Pencils: Cartoon Quotes from Inspirational Folks and Zen Pencils Volume Two: Dream The Impossible Dream, have flown off shelves worldwide. But like all cartoonists, Than is no stranger to rigour. Ideating on quotes takes weeks and even longer, the artist outlines. "CP Cavafy's Ithaka was particularly difficult to adapt. I had the poem saved for over a year before I figured how to do it." Also challenging were Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot, Bill Hicks' It's Just a Ride and Shakespeare's All the World's a Stage.

Putting his idea to paper is an eight-step process involving drawing thumbnails and roughs, referencing, more pencilling, finalising panels, inking, lettering and colouring. The last – the most tedious step of all – is his least favourite.

"I don't hate colouring, but I don't enjoy it as much as drawing or inking. Digital colouring is monotonous and labour-intensive," says Than. "It's painful, but the rewards are huge as colours bring comics to life."

He also lets one in on his artistic Achilles heels: drawing feet, cars, buildings and animals aren't his strong suits, he admits, and neither are crowds. Than has also drawn flak from some quarters for allegedly taking some quotes out of context and labelling legitimate criticism as trolling in his The Artist-Troll War series. But such episodes have given him a thicker skin, he insists. "An artist can't please everyone. Now I'm confident to just do the comics I want to do, put them out into the world and try not to think too much of what everyone else thinks."

His Burmese roots may not have huge bearing on his approach to art, but Than expresses his inclination to visit Myanmar in the future. As for Zen Pencils being an indefinite project, he's unsure: "I'd like to write my own stories, using my words and dialogue – but no plans for that anytime soon. I absolutely love working on Zen Pencils and see myself continuing it for the foreseeable future."

Gavin Aung Than has used his childhood and subsequent cartooning influences – Looney Tunes, The Simpsons, MAD, Beano and Dandy, Tintin, Asterix, Peanuts and his all-time pick, Calvin and Hobbes, to shape him into an artist delivering feel-good nuggets far superior than hand-me-down motivational phrases. Ask him about the genesis of the name Zen Pencils and the accompanying logo of a meditating Buddhist monk, and the artist, like his work, doesn't even try being grandiose:

"I had the name 'Cartoon Liberation' in mind and had designed the logo. I decided to show it to my friends, and one of them, who hated the name, suggested 'Zen Pencils' instead. I'm eternally grateful to that friend now."

Gavin Aung Than will be part of 'The Power of Web Comics' panel (12.45pm) and 'Special Session with Zen Pencils' (2.15pm) at the Mumbai Comic Con today.

![submenu-img]() ‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…

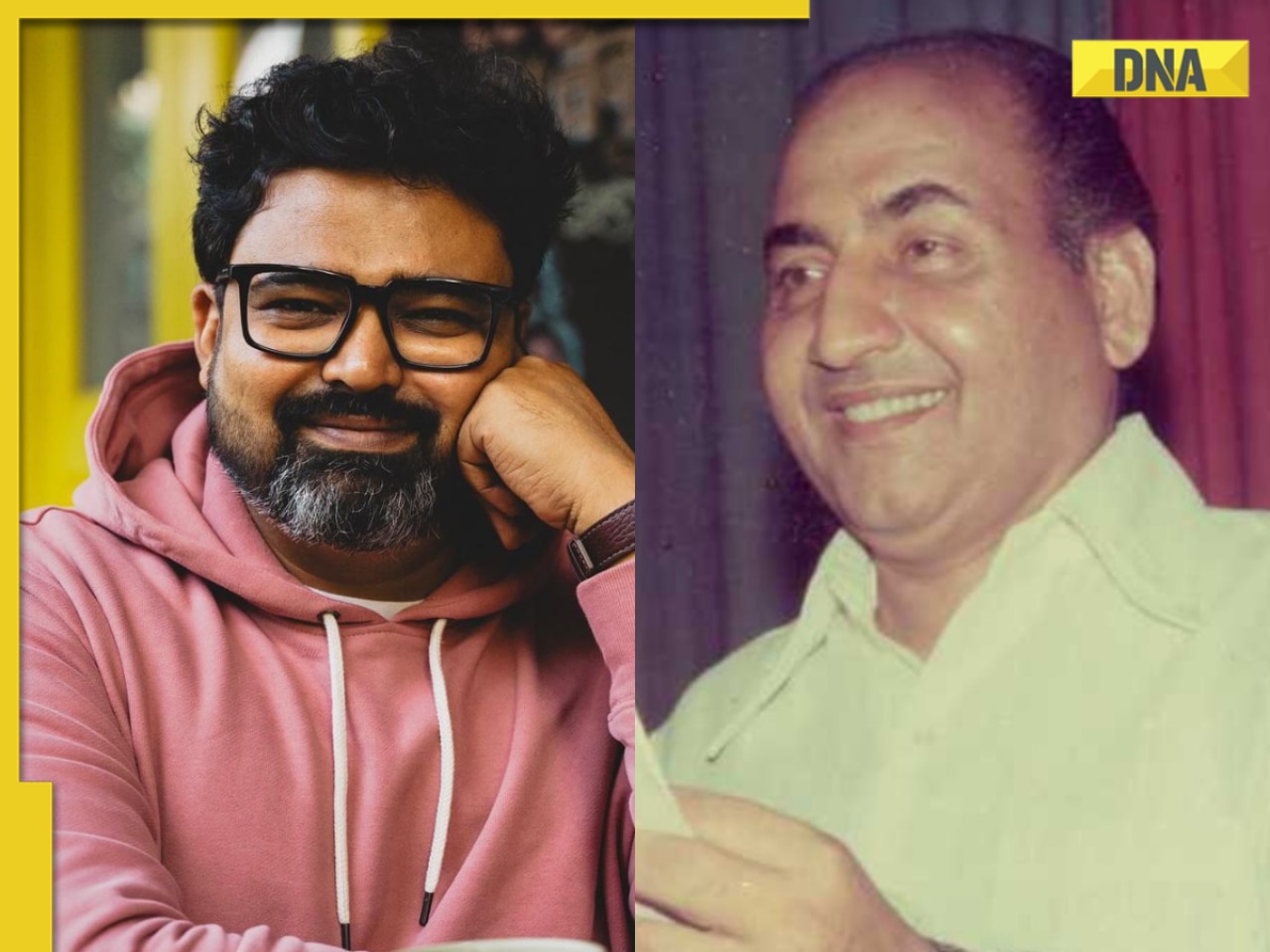

‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() 'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot

'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot![submenu-img]() JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy

JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy![submenu-img]() AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...

AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’

Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’![submenu-img]() Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..

Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore

Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...

Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals

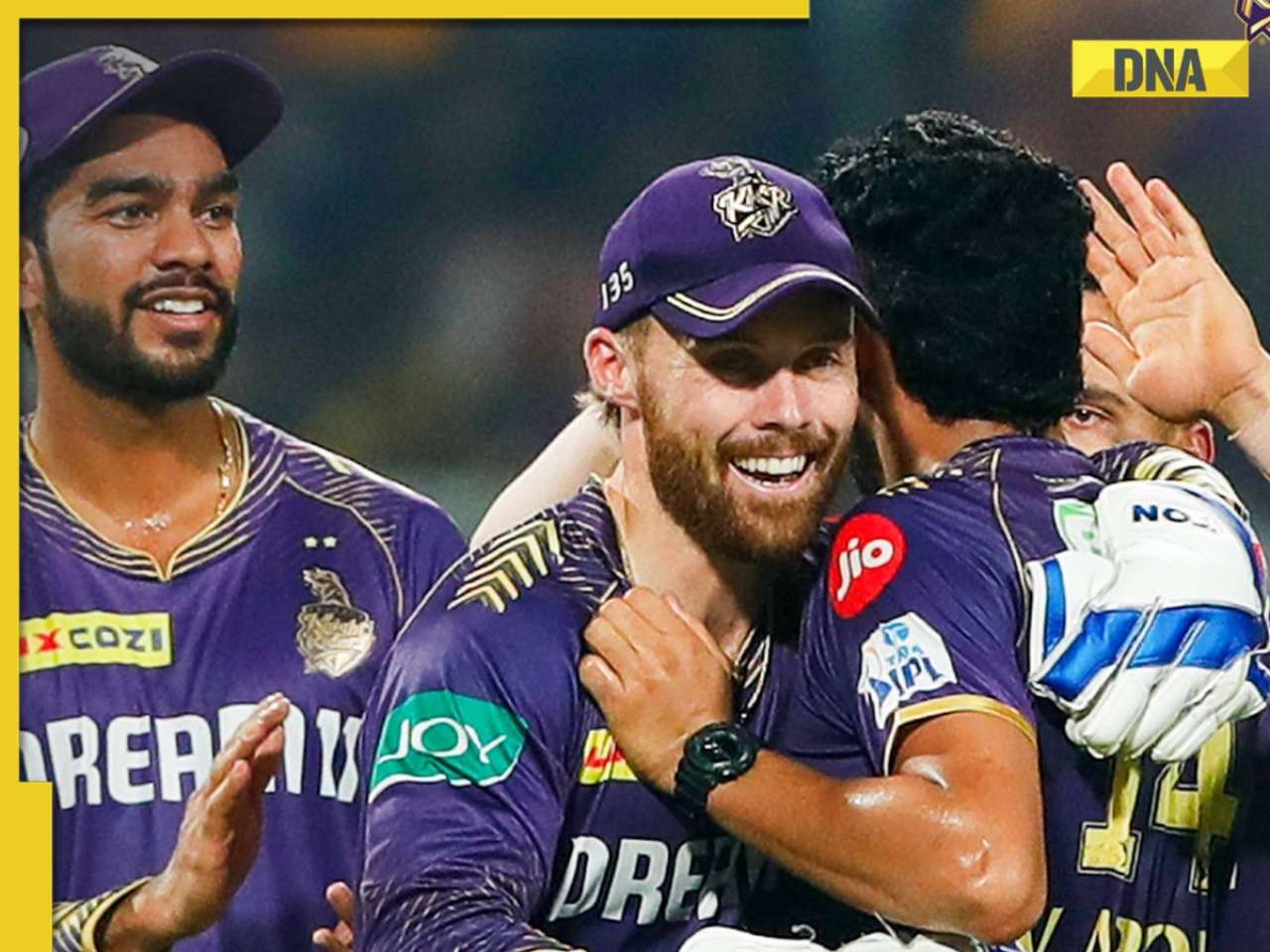

IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket

'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket![submenu-img]() 'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024

'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians

LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)

)