Tension exists over who commands the FSA.

Puffing hard on a cigarette, the Syrian rebel relived the moment earlier this week when his band of fighters was caught in Syrian army crossfire as they tried to smuggle a wounded comrade over the hilly border to Turkey.

"They fired from all directions, from above and from below. Then more soldiers appeared right in front of us," said Musa, a scrawny 28-year-old, told Reuters back in the safety of Turkey's southeastern province of Hatay, which once belonged to Syria.

"We were caught off-guard and didn't know what to do. So we fled," he said, retelling the battle and often flitting between events in a way that reflected the confusion of war. One fighter was killed on the spot, some were wounded, he said. Three rebels surrendered, three were caught as they tried to flee. Musa and the rest of his comrades managed to escape. The gunfight, Musa said, was typical of border encounters between Syrian troops and the Free Syrian Army (FSA), a loose grouping of army deserters and civilians who have taken up arms against President Bashar al-Assad.

"Sometimes we surprise them and kill or wound some of their soldiers and they are the ones who retreat," he said. Like most of the Syrians in Turkey, Musa would only give one name for fear of reprisals against his relatives at home. In civilian life, Musa is a painter and decorator. In his scruffy jeans and leather moccasins, he doesn't look like a hardened guerrilla fighter. But there are many like him in a growing and dogged network of fighters, smugglers and activists operating on the Syria-Turkey border, each with his own role. Like many, Musa lives with his family - a wife and one son - in one of several refugee camps in Hatay. He fled his border village soon after the anti-Assad revolt began a year ago.

Musa joined the FSA when it was formed months later. He talks of it as a quasi-conventional force with units and ranks, commanded by officers who have defected from the Syrian army, although some rebels contest who is really in charge.

"We are two groups of about 70 men in total. Each of our groups has a station in Syria near the border. Everyone knows which group they belong to. We know who our individual commander is. We have discipline," Musa said. FSA commanders based on both sides of the border may control the fighters in this vicinity, but the chain of command is far more tenuous for locally organised rebel groups operating deeper inside Syria, even if many of them proclaim loyalty to the FSA. Because Musa knows the area, he guides refugees or wounded soldiers into Turkey without being spotted by Assad's troops. His commander, a lieutenant, operates in Syria, he said. In Reyhanli, another border town further to the north, Abdul, who heads a group that ferries supplies to rebels, said the Syrian army was expanding its presence along the frontier.

"They now have soldiers at lookout posts every 100 metres (yards) with heavy machineguns and snipers. We pass at night. The FSA knows some routes to avoid being seen," said Abdul. "The Syrian soldiers don't like to come out at night because they do not know the area. They start patrolling around 4 or 5 in the morning. We cut tunnels through the thick thorn bushes but it is still very difficult to move through," he said. Abdul and his men smuggle medicine, food, blankets and, when he can get hold of them, weapons to the rebels in Syria.

"I am the best smuggler in Turkey. Before the revolution I could smuggle you a tank into Syria," Abdul boasts with a smile. But weapons have become scarce and prohibitively expensive.

"A Kalashnikov used to cost between $100 to $200 without ammunition. Now it costs $1,500 dollars. A bullet for a Kalashnikov used to cost 25 Kurus (15 US cents), we now offer 7 liras ($3.8) for one bullet and we can't get any," he said.

Visiting a Reyhanli hospital, Abdul said a wounded fighter had vented his anger at the logistical shortcomings, saying: "Where are our supplies? You were supposed to send us weapons, blankets and food. You haven't sent us anything."

Tension exists over who commands the FSA. Most fighters pledge allegiance to Riad al-Asaad, a former Syrian army colonel who founded it and who lives under Turkish protection in Hatay. But some said his position was only nominal and the real command lay with officers who had stayed to fight inside Syria.

"There are two armies: first, the one that fights and second, the one that sits in Turkey and drinks tea and coffee," said Abdul, showing mobile phone pictures of rebels posing with assault rifles that he said were taken in Syria this week.

"These are the real Free Syrian Army," he said. Colonel Asaad, along with some former generals and other officers stays in a refugee camp at Apaydin, some 20 km (13 miles) from Antakya, Hatay's main city, near the Syrian border. Turkey closely monitors his movements and he cannot receive visitors without Turkish government permission.

Unlike the other refugee camps, people are rarely seen entering or leaving the Apaydin camp and traffic is not allowed to stop nearby. Whatever their internal disputes, all the fighters interviewed agreed on one point.

"We need weapons, we need ammunition, we need a no-flying zone. If they (the international community) give us this, we don't want anyone to come and fight for us," said Musa.

"They are firing on us with tanks. My bullets are nothing against these tanks. We started this and we will not give up. Until Assad has gone, we will not stop."

![submenu-img]() ‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…

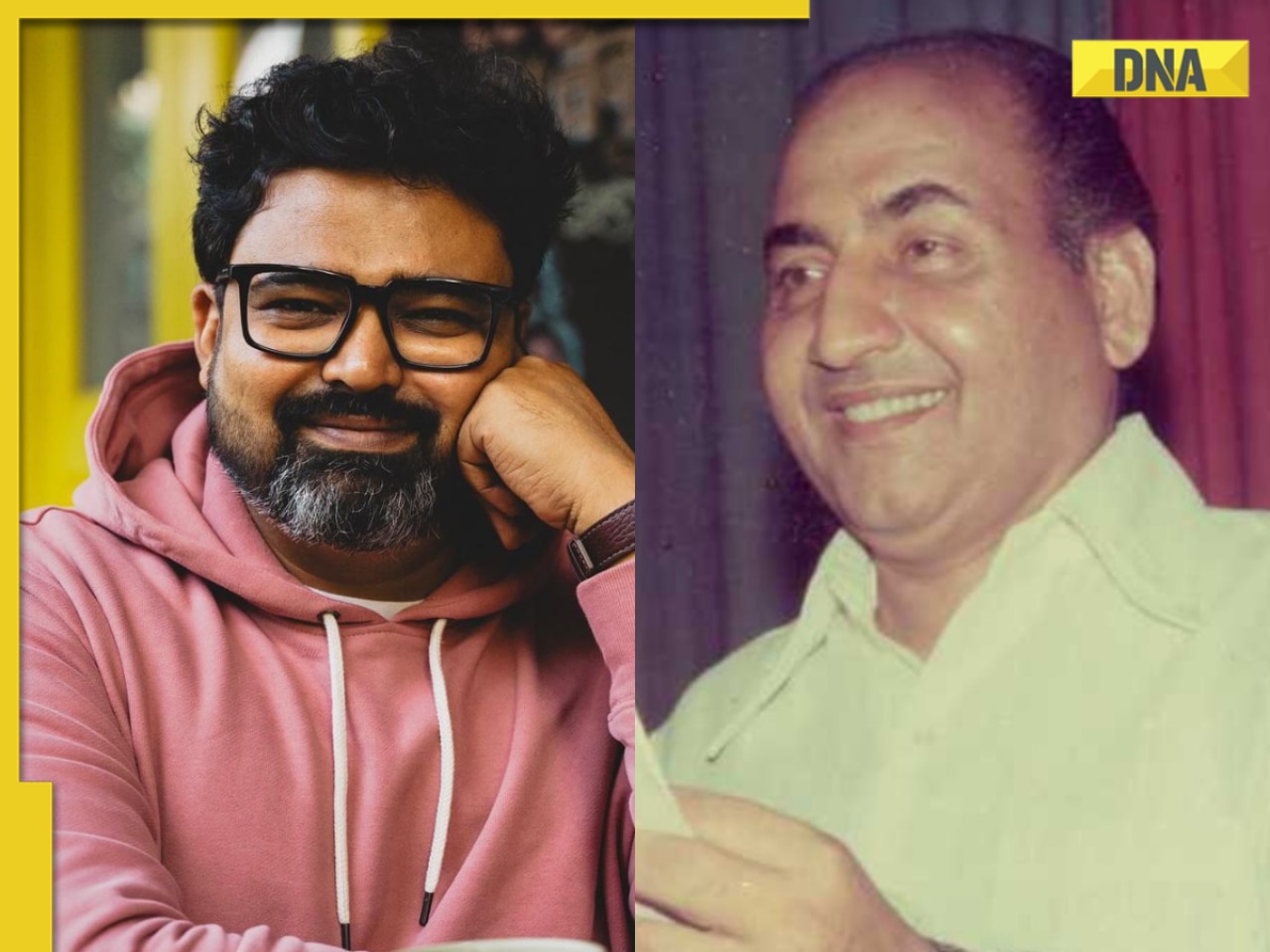

‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

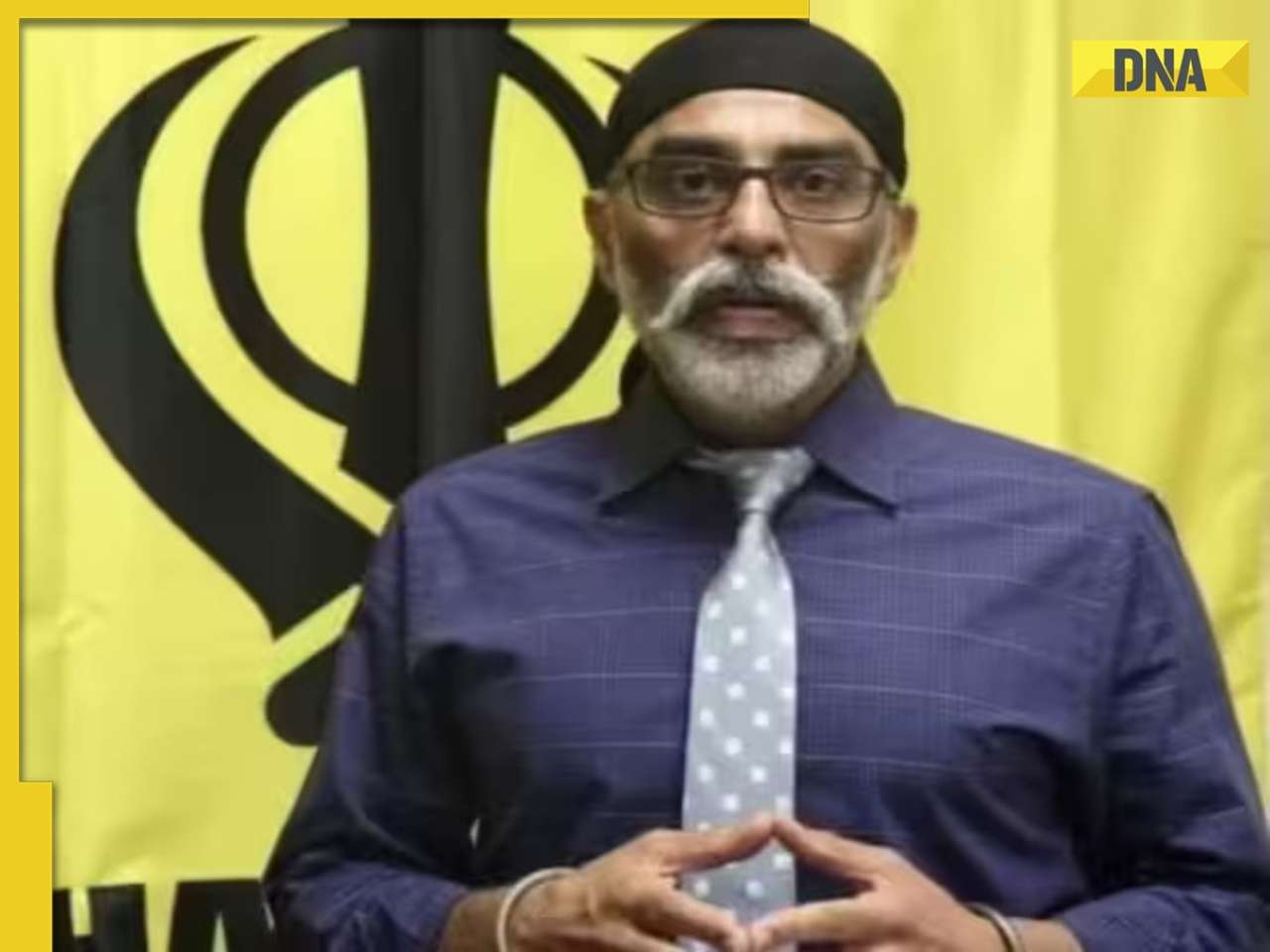

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() 'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot

'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot![submenu-img]() JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy

JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy![submenu-img]() AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...

AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

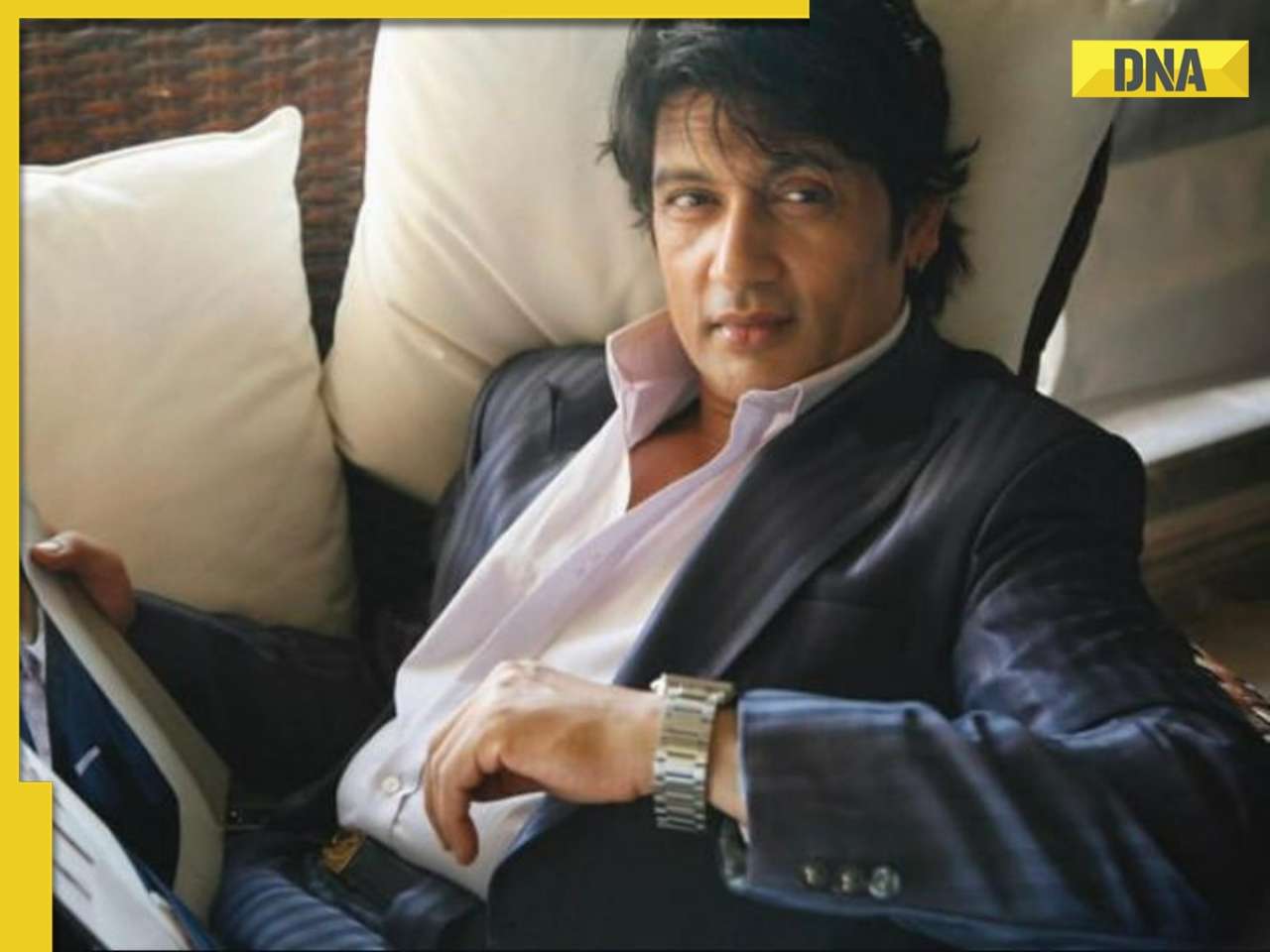

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’

Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’![submenu-img]() Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..

Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore

Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...

Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals

IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket

'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket![submenu-img]() 'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024

'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians

LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)