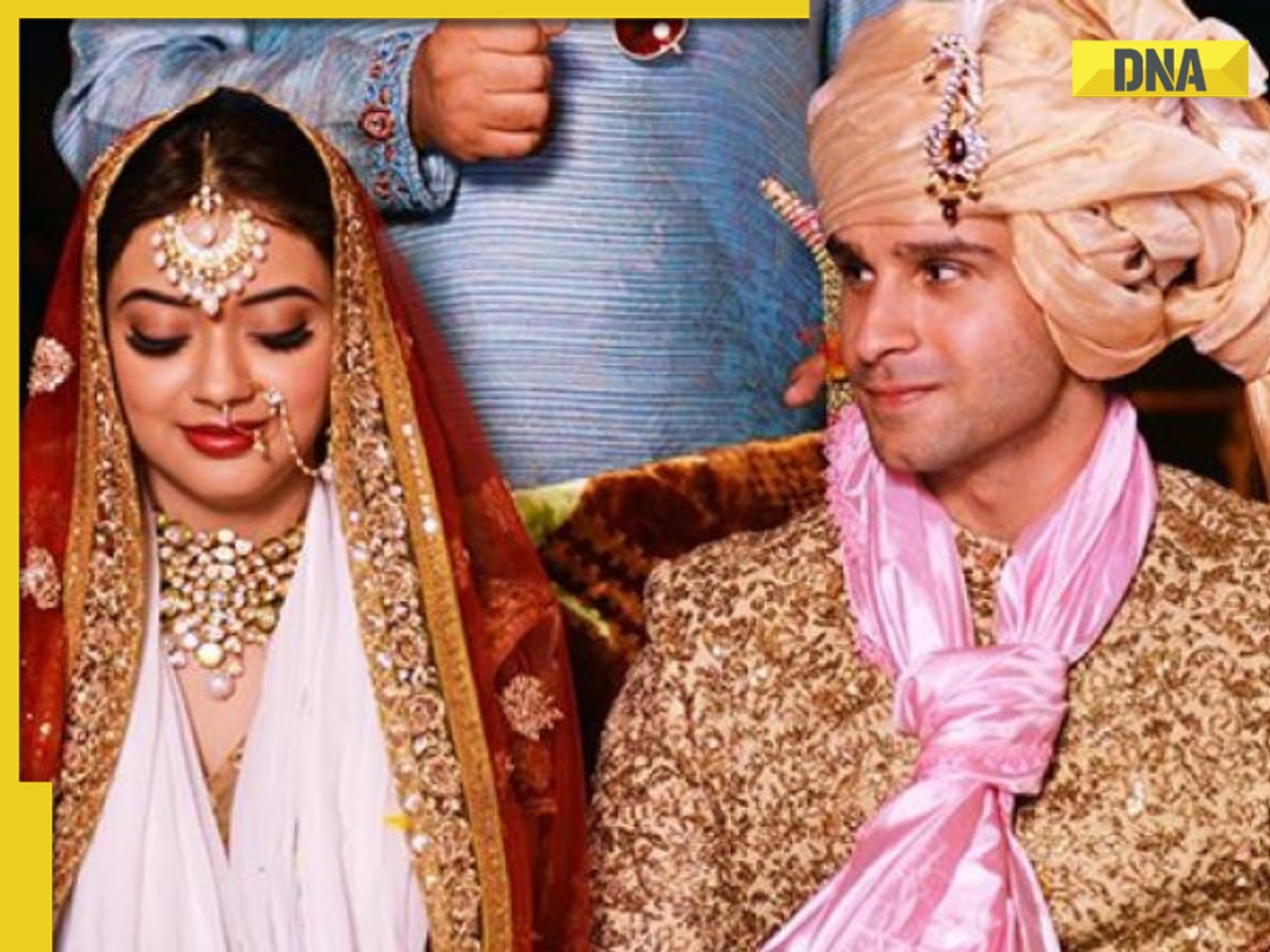

This is the happiest day of my life,” says Zebunnisa Jamadar, tears rolling down her cheeks, as she watches her daughter Isa Ali enter into wedlock with Nikhet AA Jaffar

AMRAVATI/AKOLA AND BULDANA:This is the happiest day of my life,” says Zebunnisa Jamadar, tears rolling down her cheeks, as she watches her daughter Isa Ali enter into wedlock with Nikhet AA Jaffar.

“I had lost all hope of getting my daughter married when my husband died four years ago, leaving behind mounting debts, two sons, and a daughter,” the 59-year-old widow from Vidarbha says.

With just about enough to make ends meet, Zebunnisa spent many a sleepless night on her charpoy waiting for a miracle. Her prayers were finally answered when her daughter, along with 11 other girls, tied the knot in a mass marriage on May 21. The ceremony was simple, but the electric expression on the faces of the parents made up for the lack of fireworks.

Vidarbha, in the news for debt-ridden farmers committing suicide, is scripting a silent reform in Maharashtra’s extortionist marriage market, where ostentation and fat dowries bring ruin upon thousands of families. The region, ravaged by an agrarian crisis, is seeing low-budget community marriages fast gaining acceptance among the people.

Despite the no-frills wedding, Isa Ali is all smiles. She can’t believe she got married under the same roof as Kalpana Dongre, the daughter of Amravati mayor Ashok Dongre. Kalpana, 22, isn’t complaining either. “I am proud that I shared my special moment with 11 other couples,” she says.

“Mass marriages are the best way to eradicate social evils like dowry,” says Kalpana’s mother Seema Dongre. “At the same time, they promote community bonding.”

Thanks to the trend, Kalawati Bandurkar, whose husband committed suicide in 2005 leaving behind nine daughters, breathes easy. Because of spiralling wedding expenses and the dowry system, Kalawati and many other women like her thought they would never be able to get any of their daughters married. “My husband was reeling under mounting debt,” says Kalawati. “He used to tell me daily that it was a shame we weren’t able to marry our daughters off. Ultimately, he killed himself.”

Taking the initiative are girls from the region, many of whom have witnessed their uncles, brothers, and fathers toil day and night to collect money for their weddings. “Marriages are seen as an occasion to exhibit one’s status,” says social activist Mohan Jadhav of the Vidarbha Jan Andolan Samiti. “And the bride’s father goes bankrupt trying to live up to societal obligations.” Many families continue to spend lavishly on ‘aher’, a tradition of exchanging gifts during marriages. “This must stop,” say social activists.

Munna Bolenwar, a farmer in Hiwra-Barsa village in Yavatmal, says, “Marriage expenses are hitting the roof while our income is dwindling. The only way we can get our daughters married without incurring additional debts is through mass weddings.”

What started as an initiative to help poor farmers has now caught the fancy of urban brides and grooms as well. Recently, the sleepy town of Gadchiroli saw Arti Naitam, an air-hostess, tie the knot with Rahul Atram, an engineer with a Japan-based MNC, at a mass-marriage ceremony. “It is good that educated and well-to-do couples are coming forward to set an example for others,” says farmers’ leader Vijay Jawandhia.

What started the reformThe trend has its roots in a door-to-door government-sponsored survey in 2005. Vidarbha was making news for an alarming number of farmer suicides. This prompted the government to commission a survey to look into the economic constraints faced by the farmers. Marriage expenditure was cited as one of the reasons for the mounting economic burden and growing indebtedness of cotton farmers.

The survey also revealed that there were as many as three lakh unmarried girls in the crisis-ridden region. The findings led to the formulation of ‘Shubha-Mangal’ — a government-supported mass marriage programme. Various NGOs and social organisations conduct mass weddings for which they are paid Rs1,000 per couple by the goverment. The government also gives Rs10,000 to each couple that ties the knot in a mass wedding.

So far, nearly 19,000 weddings have been solemnised under the scheme in Vidarbha since February 2006. Harshwardhan Patil, Maharashtra minister for women and children’s development, says, “The response to ‘Shubha-Mangal’ has been very good.

A few months ago, we expanded the scheme to cover 29 districts of Maharashtra.” Akola collector Shrikar Pardesi feels it is one of the most effective schemes in the farmers’ relief package.

The scheme’s success has seen many socio-political organisations come forward and host such events without government assistance. Political parties, too, have joined the party in the hope that such an initiative will help them to garner votes. In April, the BJP hosted a big community wedding, where 200 couples got married in the presence of about 10,000 guests. Every year, PWD minister Anil Deshmukh also hosts community marriages in his constituency Katol.

Corruption has crept inBut all is not rosy. Pardesi has put the scheme on hold in his district, following reports of fraudulent marriages and unlawful weddings of minor couples, and ordered an inquiry into the matter. “We have blacklisted the NGOs involved and not released the money yet,” he says. “I don’t want the objective of the programme to become a casualty of corruption.”

h_jaideep@dnaindia.net![submenu-img]() Nagaland Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: Full list of winner and loser candidates will be announced soon

Nagaland Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: Full list of winner and loser candidates will be announced soon![submenu-img]() Meghalaya Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: Full list of winner and loser candidates will be announced Soon

Meghalaya Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: Full list of winner and loser candidates will be announced Soon![submenu-img]() Delhi Lok Sabha Election Results 2024: Full List of Winner and Loser Candidates will be announced Soon

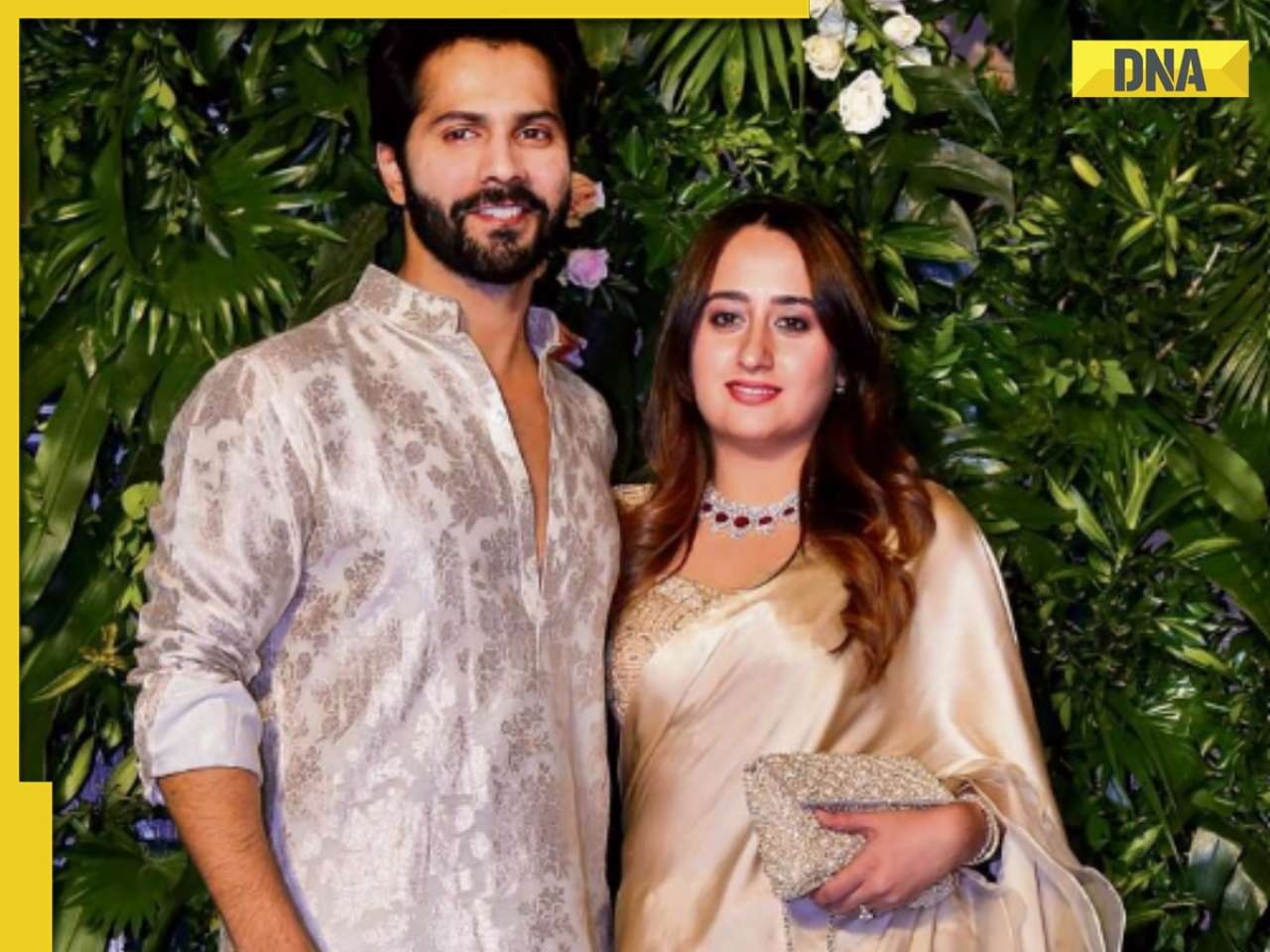

Delhi Lok Sabha Election Results 2024: Full List of Winner and Loser Candidates will be announced Soon![submenu-img]() Varun Dhawan, Natasha Dalal blessed with a baby girl, grandfather David Dhawan shares good news

Varun Dhawan, Natasha Dalal blessed with a baby girl, grandfather David Dhawan shares good news![submenu-img]() DNA TV Show: Opposition rejects exit polls results, demands counting of postal ballots first

DNA TV Show: Opposition rejects exit polls results, demands counting of postal ballots first![submenu-img]() Meet man who won medals for India in bodybuilding, cracked UPSC in 1st attempt, resigned as IRS after 10 years due to...

Meet man who won medals for India in bodybuilding, cracked UPSC in 1st attempt, resigned as IRS after 10 years due to...![submenu-img]() IIT-JEE topper with AIR 1 joins IIT Bombay, gets job at NASA as scientist, leaves to work as…

IIT-JEE topper with AIR 1 joins IIT Bombay, gets job at NASA as scientist, leaves to work as…![submenu-img]() Meet man who grew up in orphanage, began working at 10 as cleaner, delivery boy, then became IAS officer, is posted at..

Meet man who grew up in orphanage, began working at 10 as cleaner, delivery boy, then became IAS officer, is posted at..![submenu-img]() Meet UPSC topper who cleared JEE Advanced, went to IIT Kanpur, left high-paying job to become IPS officer, secured AIR..

Meet UPSC topper who cleared JEE Advanced, went to IIT Kanpur, left high-paying job to become IPS officer, secured AIR..![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam twice, left IPS to become an IAS officer, secured AIR...

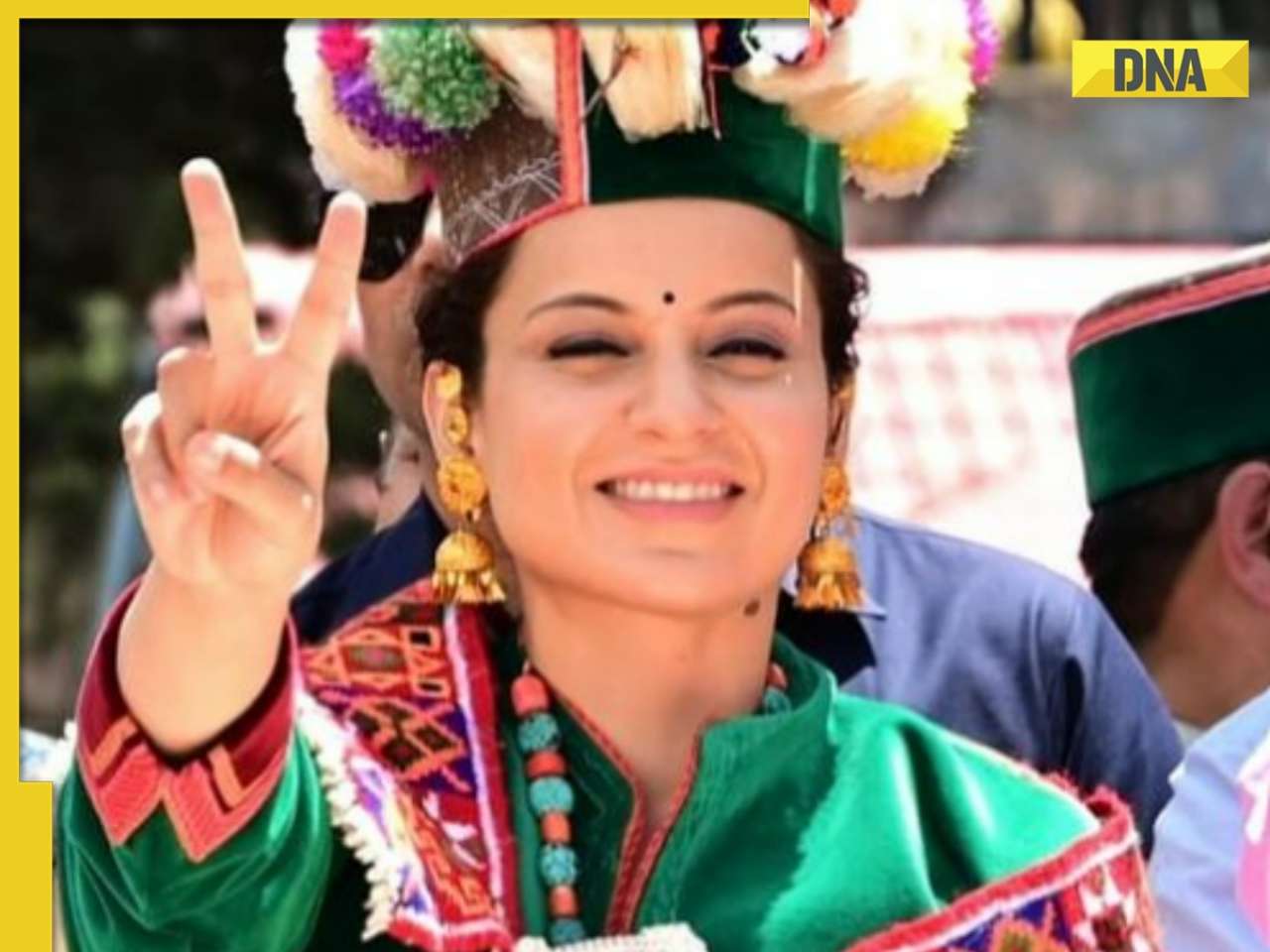

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam twice, left IPS to become an IAS officer, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo

DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here

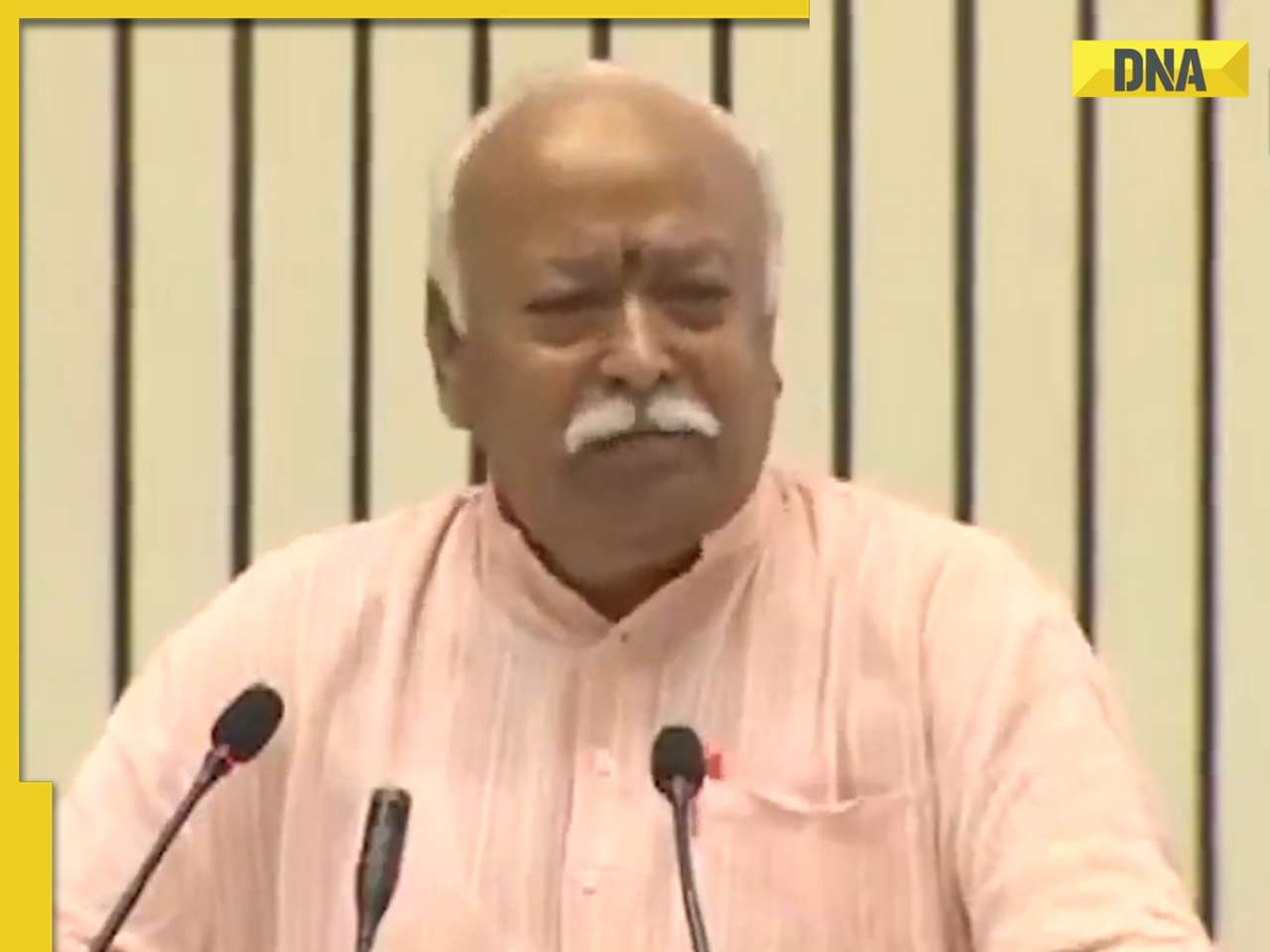

DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() Lok Sabha Elections 2024: What are exit polls? When and how are they conducted?

Lok Sabha Elections 2024: What are exit polls? When and how are they conducted?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() Varun Dhawan, Natasha Dalal blessed with a baby girl, grandfather David Dhawan shares good news

Varun Dhawan, Natasha Dalal blessed with a baby girl, grandfather David Dhawan shares good news![submenu-img]() Natasa Stankovic's friend Aleksandar Ilic slams troll saying he broke her marriage with Hardik Pandya: 'Should I...'

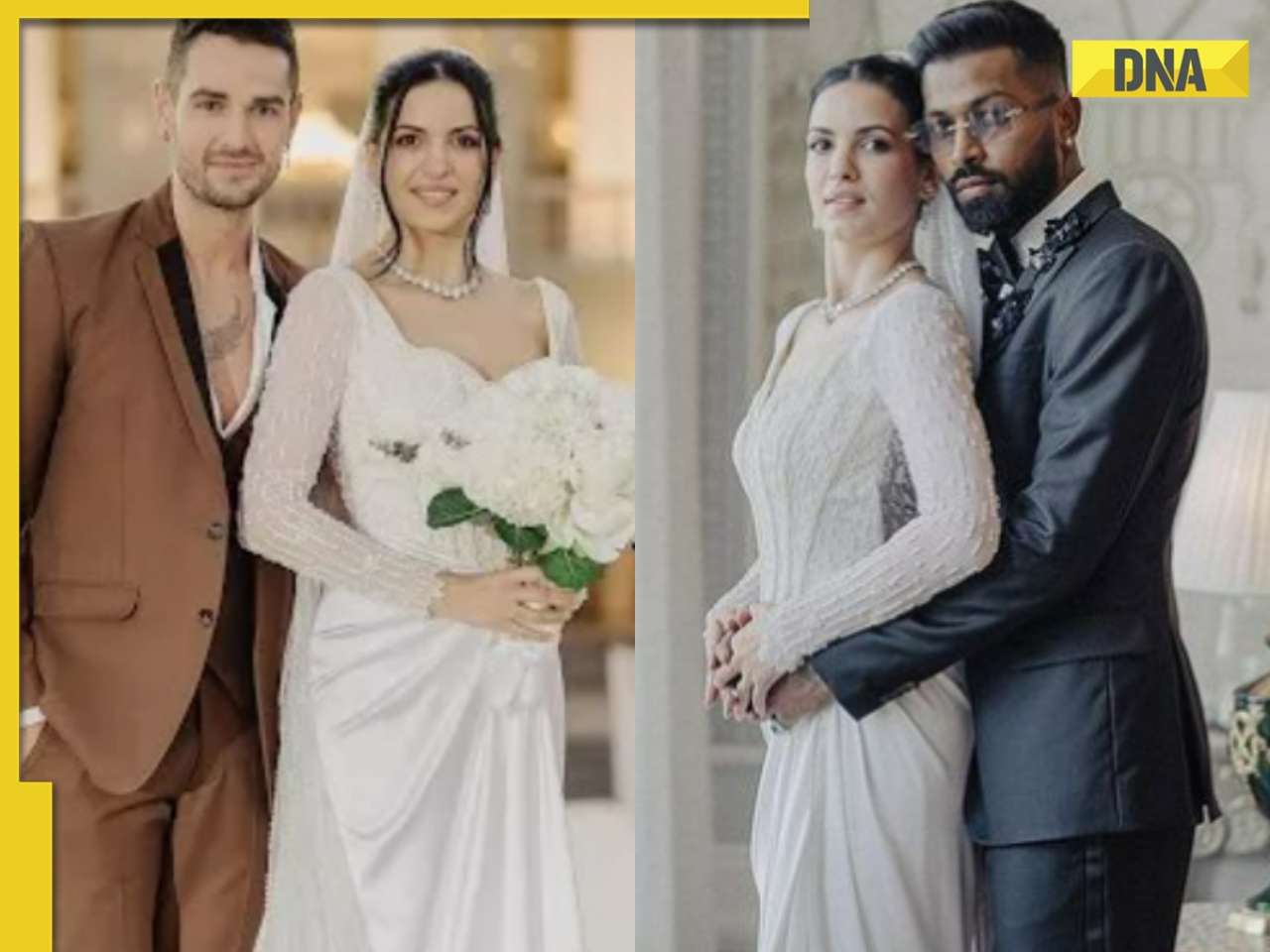

Natasa Stankovic's friend Aleksandar Ilic slams troll saying he broke her marriage with Hardik Pandya: 'Should I...'![submenu-img]() Neha Sharma reveals if her father's political career has backfired on her in Bollywood: 'I am not here to promote...'

Neha Sharma reveals if her father's political career has backfired on her in Bollywood: 'I am not here to promote...'![submenu-img]() Venom The Last Dance trailer: Tom Hardy and his symbiote fight aliens in trilogy's finale, film to release on...

Venom The Last Dance trailer: Tom Hardy and his symbiote fight aliens in trilogy's finale, film to release on...![submenu-img]() Ammy Virk defends Diljit Dosanjh's decision to not wear a turban in Amar Singh Chamkila: 'You can't stop the trolls'

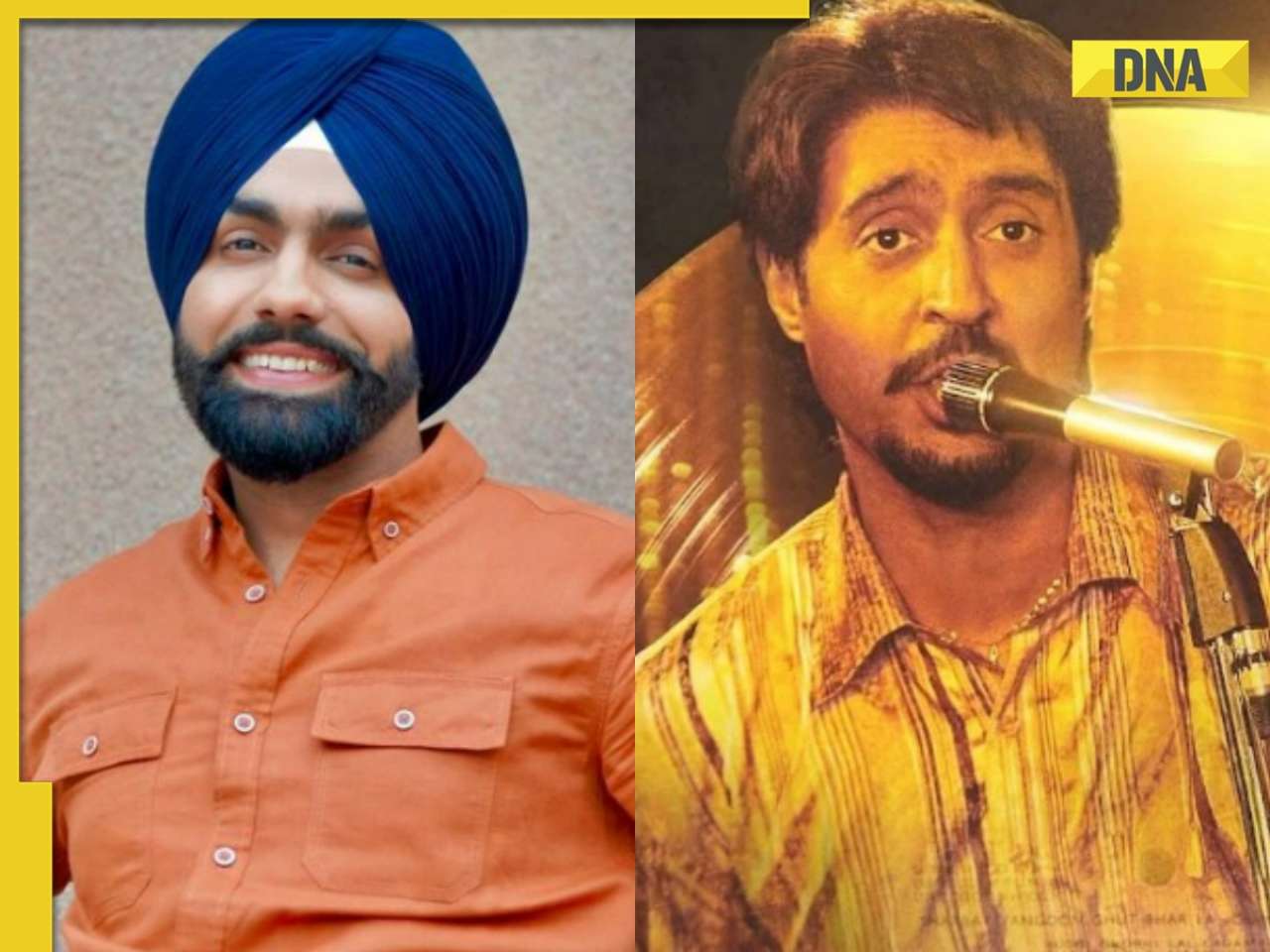

Ammy Virk defends Diljit Dosanjh's decision to not wear a turban in Amar Singh Chamkila: 'You can't stop the trolls'![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani stuns during Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding celebrations in Italy

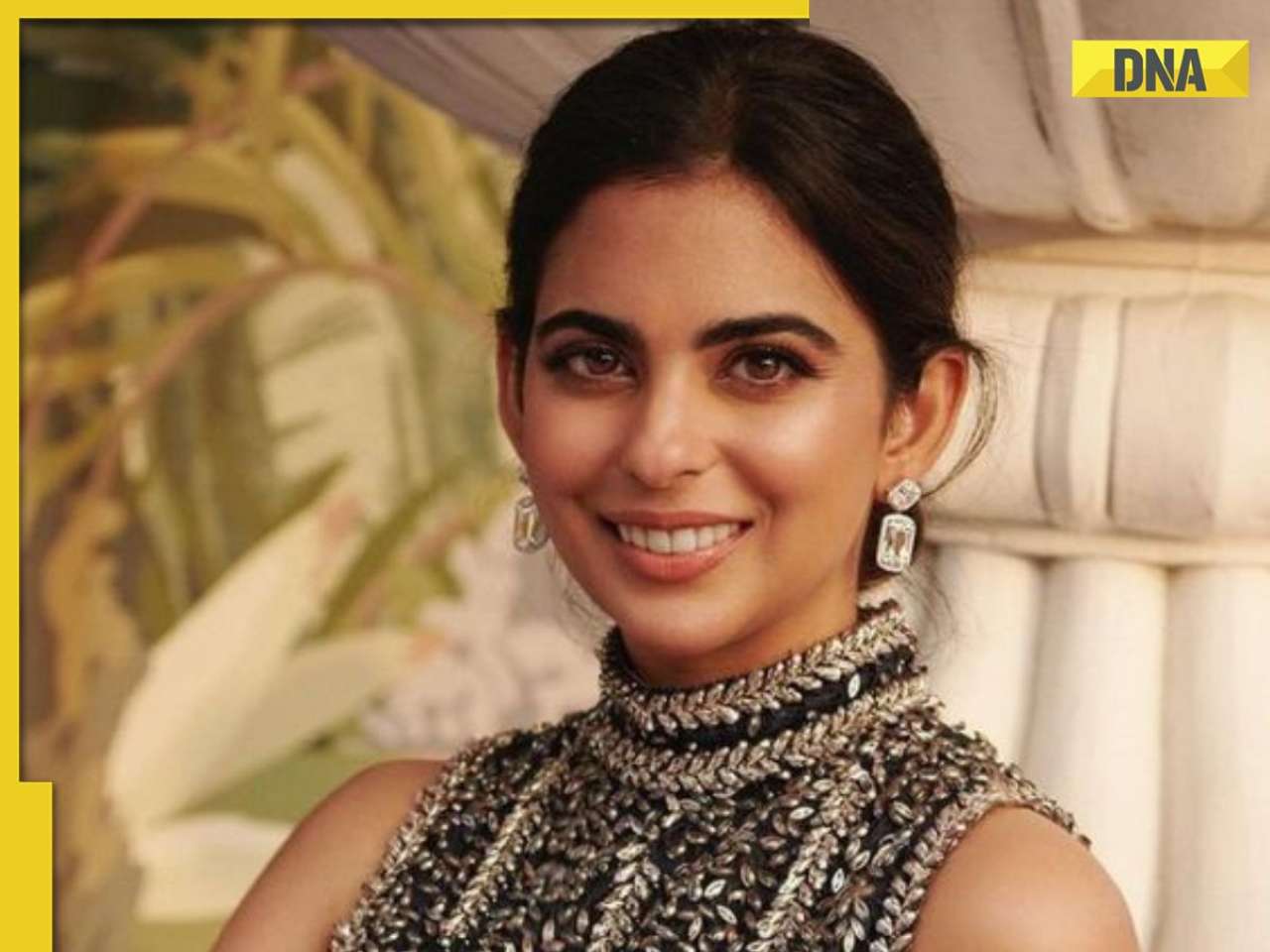

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani stuns during Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding celebrations in Italy![submenu-img]() Former air hostess reveals harsh realities of flight attendant job, says 'people think...'

Former air hostess reveals harsh realities of flight attendant job, says 'people think...'![submenu-img]() 'Egg fry or fish fry': Viral video shows egg dish looking like goldfish; watch

'Egg fry or fish fry': Viral video shows egg dish looking like goldfish; watch![submenu-img]() Viral: IndiGo crew protects passengers from rain, watch heartwarming video

Viral: IndiGo crew protects passengers from rain, watch heartwarming video![submenu-img]() This variety of mango costs Rs 2.50-3 lakh a kg, know why

This variety of mango costs Rs 2.50-3 lakh a kg, know why

)

)

)

)

)

)