Demand for apartments has reportedly fallen nationwide in the past week; reports say some developers have cut prices by 5-10% in Beijing.

China’s ongoing efforts to deflate a frothy property bubble could accelerate the risk of default by local investment companies that went on an orgy of debt-driven infrastructure spending — and prove a serious drag on economic growth, warn economists.

Just this week, Chinese authorities took a slew of policy actions

to curb excessive speculation in the property market that has sent prices soaring even beyond the big cities. They raised the downpayment requirement for home buyers to check leverage, raised interest rates on second mortg-ages, tightened lending norms to disincentivise speculation by “non-residents” and are reportedly planning a property tax in four cities — Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Chongqing.

To observers, this multi-pronged crackdown, which targets vendors, buyers, banks and local governments, means only one thing. Chinese authorities are moving “aggressively to deflate a number of housing bubbles around China,” says Standard Chartered economist Stephen Green.

“Beijing has decided that China’s property market needs a short, sharp correction,” adds Societe Generale economist Glenn Maguire. “Or to put it less delicately, an inflating bubble needs to be pricked.”

China’s property bubble has, of course, not been driven by leveraged debt. Nevertheless, says Maguire, “there has been a dramatic surge in the amount of mortgages taken out over the past year — with mortgages equivalent to almost 50% of the value of property sold at the end of 2009.” And just as mortgage debt turned up rapidly in the past year, consumers too have taken on more debt.

In response to the recent policy crackdown, demand for apartments has reportedly fallen nationwide in the past week, and there is anecdotal evidence that some developers have cut prices by 5-10% in Beijing, says Green. “Housing demand is likely to slow for at least a few months” and developers will very likely pull back from land auctions in the coming months.

But the calibrated cooling down of the property market is bad news for local governments, which benefit from land sales revenue, and which, adds Green, were “making out like bandits as their local bubbles continued to inflate.”

In particular, investment companies floated by local governments, which carry a heavy burden of debt, have emerged “as a potentially large drag on growth prospects,” reasons RBS economist Ben Simpfendorfer.

The risk, he points out, is that some local investment companies have used land as collateral to borrow money to fund uneconomic projects. “And if land prices were to fall, in the event of the property market correction, the risks of default would grow.” This linkage, adds Simpfendorfer, “further complicates the central government’s efforts to cool an overheating property market.”

China has experienced a similar problem with non-performing loans (NPLs) in the past as well. In 1999, China bailed out its banks buying 1.4 trillion yuan ($200 billion) worth of NPLs, which equated to 16% of GDP, similar to today’s estimates of likely NPLs. And that bailout did not stop China’s economy from growing. In fact, Simpfendorfer says, “nominal GDP growth was an effective way of absorbing the stock of NPLs.”

But, he says, it seems unlikely China can repeat that performance — of “growing its way out of its NPL problem”. For one, it may be difficult to turn off the credit tap — with risk of higher NPLs — if the risk of a correction in the property market requires a fiscal response to stabilise economic growth.

For another, China is yet to solve the problem of the fiscal relationship between the central and local governments; in particular, it hasn’t found a sustainable way to fund local governments.

“Policy action taken this year is crucial,” cautions Simpfendorfer. “The government must prevent a destabilising property bubble from curbing GDP growth.” Although consumer inflation has so far remained benign, medium-term inflation pressures suggest that the central bank may eventually have to tighten more aggressively than it might like to.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

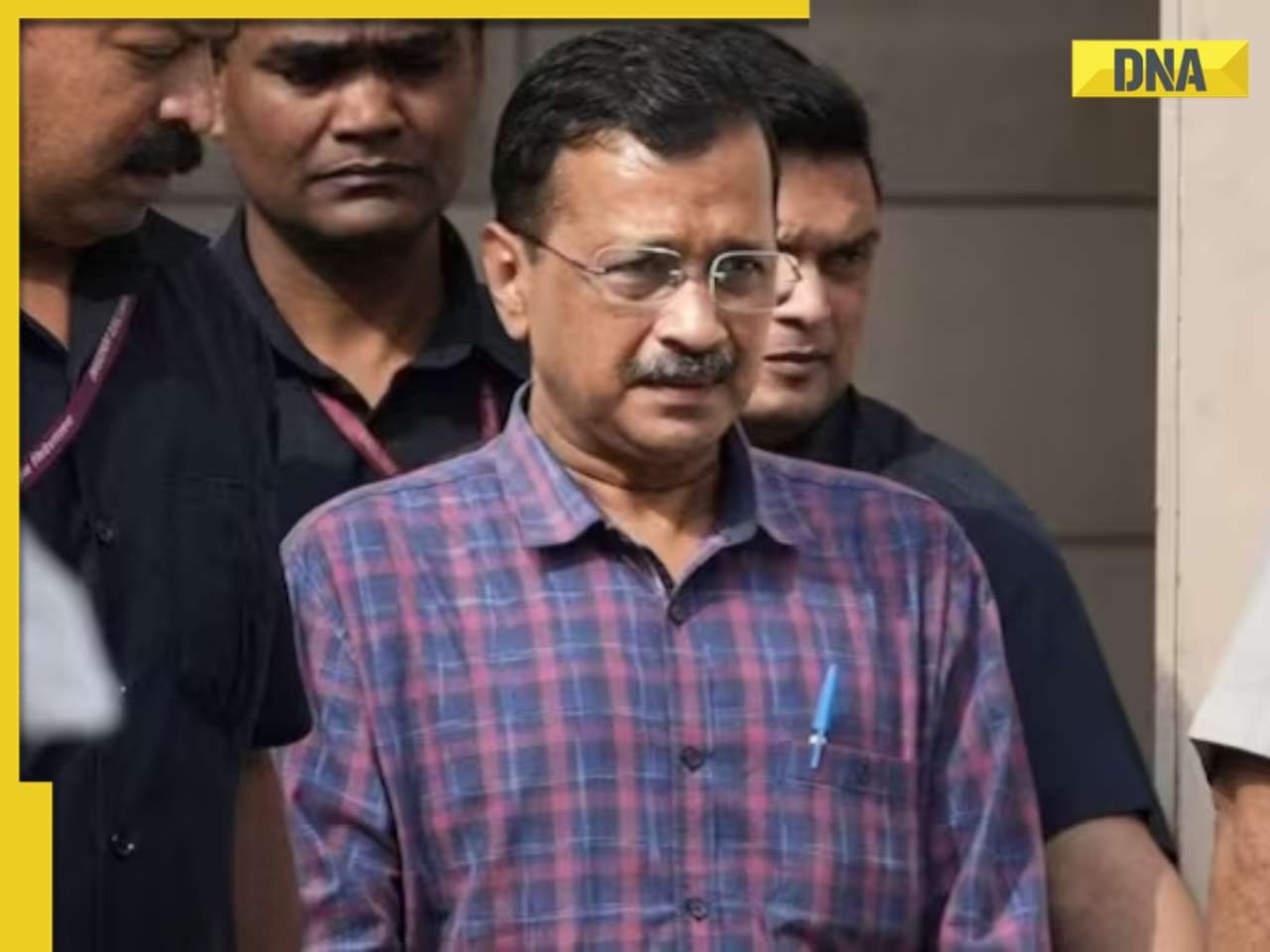

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

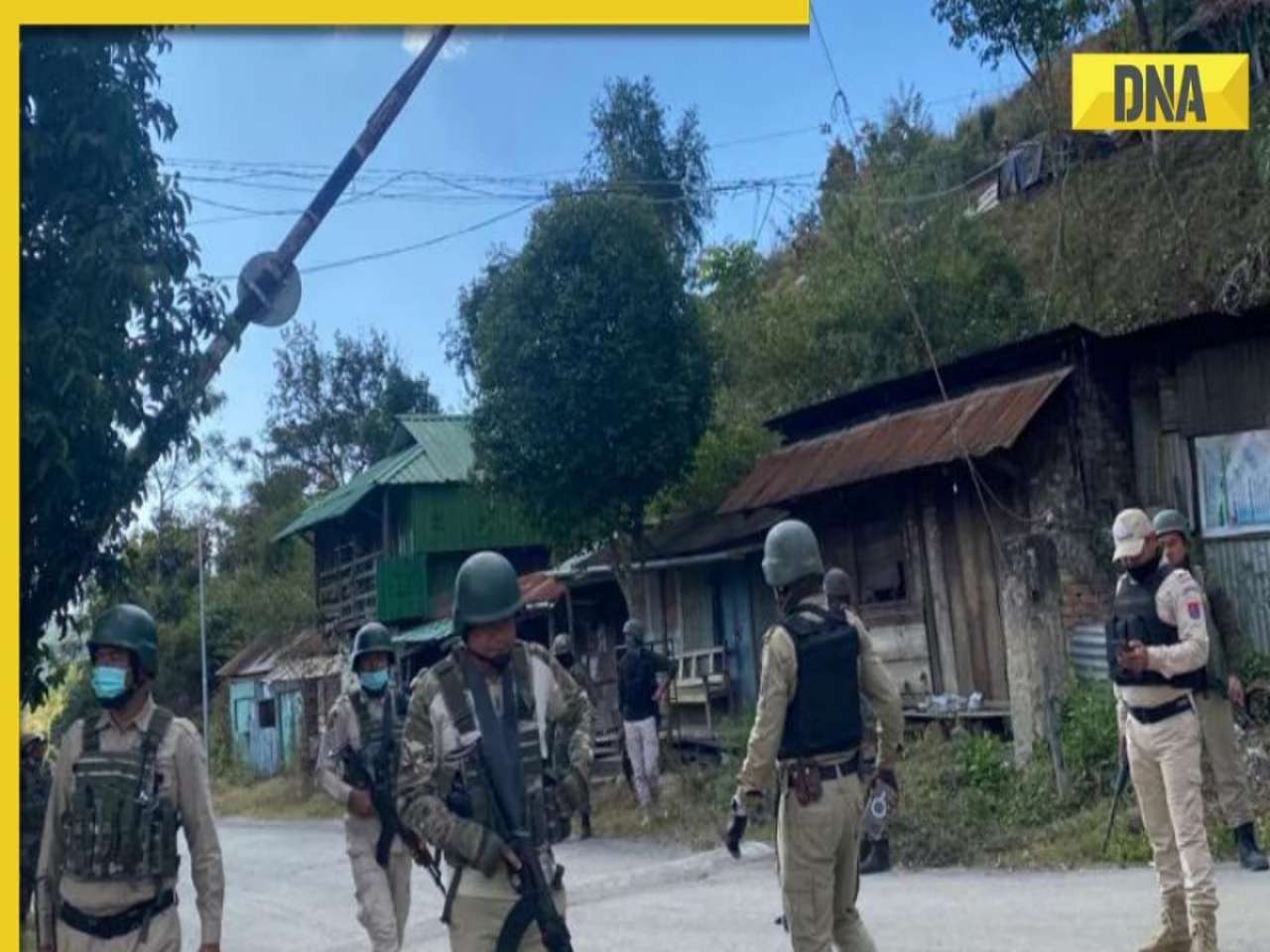

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)