A shared musical legacy binds India to South East and Far East Asia region, says Yogesh Pawar as he tracks musicologist Piyal Bhattacharya's quest to bring back the Burmese harp, a precursor to the veena still being played in that country

Historians have long spoken of a Greater India encompassing the historical, geographic and political entities of the Indian subcontinent and beyond, a connect that evolved in varying degrees with the acceptance and induction of cultural and institutional elements. But, apart from spirituality, social practices and spices, of course, what else ties India to this region, particularly South East and Far East Asia?

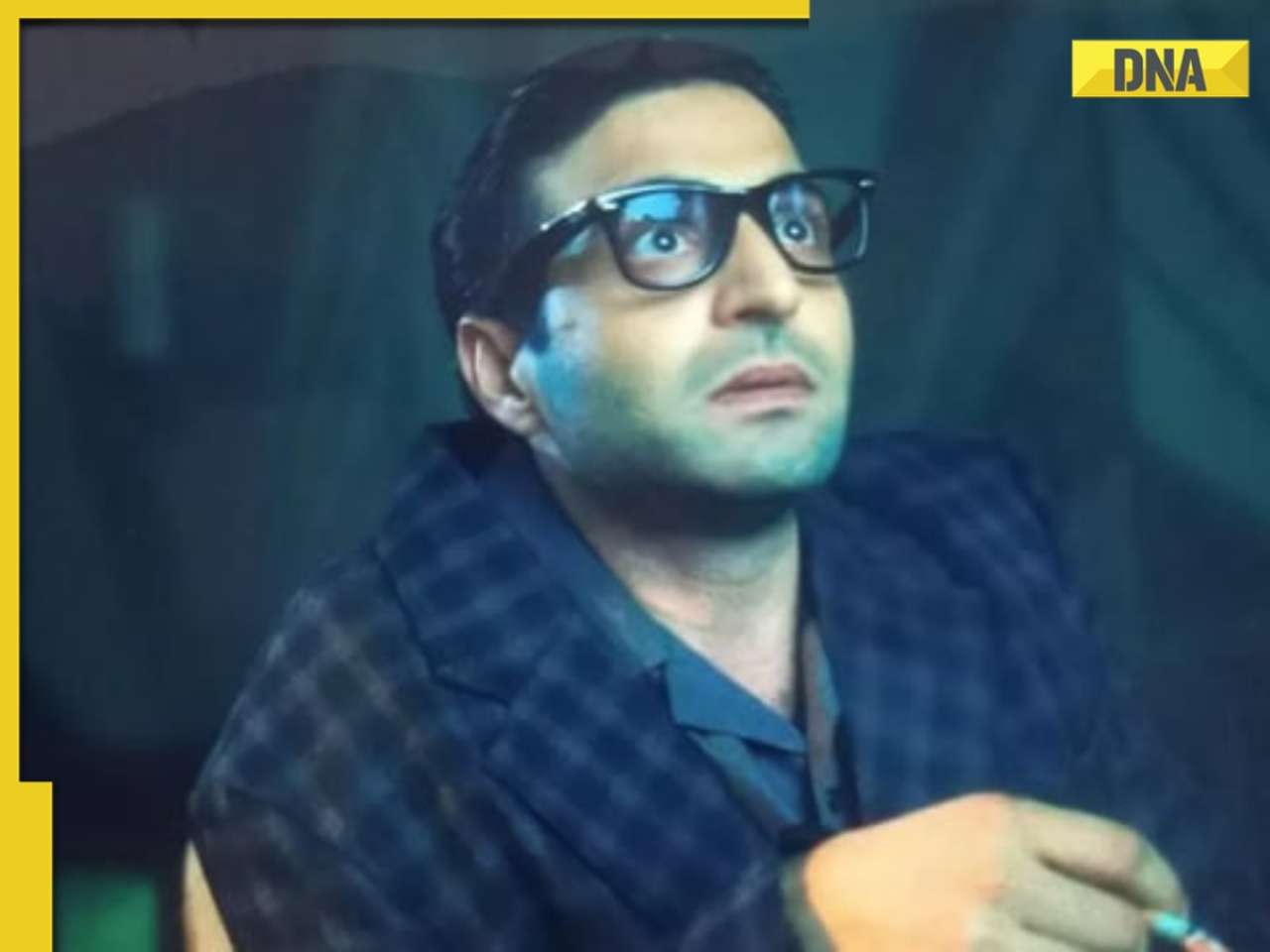

“It has to be music,” says Piyal Bhattacharya, Nāṭya Śāstra research scholar and Sangeet Natak Akademi intangible cultural heritage fellow, who is doggedly working to revive the craft of making and playing the ancient Indian harp, the precursor to the veena, which survives and thrives in neighbouring Myanmar.

It’s a piece of India’s musical legacy and the multifaceted Bhattacharya -- musicologist, Sanskrit scholar and Kathakali dancer amongst his many other callings -- is determined to battle issues of funding and bureaucratic delays to bring it back.

“In my research looking at the ancient encyclopaedic treatise on performing arts by Bharat Muni from 200 BC, I found expanding land and maritime trade from 500 BC resulted in prolonged socio-economic and cultural stimulation and diffusion of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs into regional cosmology, not only in nearer islands like Sri Lanka, Mauritius and Maldives but also across South East Asia, Far East Asia and even parts of Austronesia,” he says, recounting how his musical quest started.

It was during his pursuit in Nāṭya Śāstra that he stumbled on a discovery of a musical instrument which predates the ancient veena. “Whether Rudra, Saraswati, Chitra or Vichitra veena, they've all evolved from the Vakra veena, an arched harp. Late musicologist Acharya Brishapati's disciple Bharat Gupta once mentioned to me in 2009 how the ancient veena was not a lute like we see today. Intrigued, I asked him to send me images.”

Allyn Miner, sitar exponent and music scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, agrees. “Though by the 6th century CE, the goddess Saraswati sculptures are predominantly with the veena of the zither-style, similar to modern styles and other scholars, it was originally closer to a harp,” she points out.

One image Bhattacharya got from Gupta was from the Delhi museum depicting a relief from the Gurjari Pratihari period (8-9th century CE). “Hooked, I began to then consciously look for and found this harp in the hands of deities and the Gandharva musicians at their feet in sculptures and reliefs in ancient temples across India.”

But we are getting ahead. For this is as much a story of the discovery and potential revival of a musical instrument lost to this land as it is the story of a whimsical genius driven by his passion.

The winding road

“I don't know why my interests are so eclectic. The familiar and comfortable tires me quickly,” laughs this anthropology graduate acutely interested in Indian classical dance forms from early on. “Till the next challenge is in grasp, I'm in turmoil, hurting within.”

While learning dance and classical vocal music at Kolkata's Ananda Shankar Centre for Performing Arts, Bhattacharya happened to attend a performance by Bharatanatyam guru Dr Padma Subramaniam. “Blown away by her interpretation of the 108 basic units of dance from the Karana Prakaranam, of the Nāṭya Śāstra, I was inspired to research the treatise myself on the musical aspects.”

Though unhappy with the didactic music and dance course he was already enrolled in, Bhattacharya says his mother was strictly against quitting before the three-year stint ended. “Finally, in 1998, when I moved to Kalamandalam, Kerala, for higher studies in Kathakali, my life changed under the gurukul system with its emphasis on rigorous training, traditional teaching techniques and its stress on intricate detail at the five-year course.”

That bond with fellow dancers and teachers stayed strong later too. He was often hosted by Kalamandalam alumnus and friends on his regular travels down South to buy books on Indology, Orientalism and other dance related subjects. “You see, the Communist government had banned sale of Sanskrit books in West Bengal so I'd keep going to Chennai to buy books or read up in libraries there.”

Bhattacharya remembers the next few years spent “like a vacuum cleaner” pursuing several performing arts simultaneously. He was pursuing Sanskrit at Kolkata university, musicology under Pradip Ghosh, dhrupad under Pt Falguni Mitra of the Bettiah gharana, pakhawaj under Apoorva Lal Manna, Saraswati veena under maestro Vijaya Varlakshmi for two years followed by Rudra veena under Pt Subir Mishra (“This customs officer would not only teach me for free but also feed me every time I went home to learn”).

But weren't these far too many turns to take? “I don't see it like that. Every single thing I learnt has helped me become a holistic musician. I'm glad I fortified myself with this knowledge before plunging into unchartered waters.”

And those waters were both tricky and treacherous, he discovered when he made sketches based on the image that Bharat Gupta had sent him and began looking for a craftsman to make the harp. After being turned down several times, veena legend Karaikudi Subramaniam helped him find a craftsman in Chennai who agreed to make the harp in 2009. “I got one made for Rs.35,000 only to struggle for three years to discover how to tune and play what has since remained an ornamental showpiece.”

The Burma bridge

He found late Sanskrit scholar, Indian museologist, art historian and epigraphist Calambur Sivaramamurti's book Nataraja in Art,Thought and Literature which talks of India's ancient musical legacy surviving in Myanmar. “Thanks to the internet and a smart phone a student gifted me I was able to find the Burmese harp called saung-gauk. My search led me to Rangoon-based Moung Win Htwe, a well-known craftsman who could help.”

Principal of the Rangoon music school Geeta Mait, Thun Thun agreed to teach him if he came over for $10 per session. “I was told it'll cost $600 to stay for a month.” But that was not all. Each of the seven, nine and 15 string harps he wanted to buy would cost $200, while the two 21-stringed one would cost $350 each. “I found that a direct flight was more expensive and a cheaper alternative was flying via Bangladesh (Rs 15,000 round-trip). The visa itself would cost Rs 3,000.”

He tried to raise funds from both private and government sources but nobody helped. “Vijay Kichlu of the Sangeet Research Academy, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations and Bimla Poddar of Jnana Pravaha all said they had no funds.”

Fortunately, the culture ministry last year approved of a production grant of Rs 75,000 each to him and his student and Sangeet Natak Akademi gave him a fellowship of Rs.1 lakh. “I added to that by liquidating all my parents savings and mine and borrowed some more. Finally my student Shubhendu Ghosh and me left for Myanmar on February 10, 2016.”

While the teacher U Win Maung was very kind and taught Bhattacharya five hours daily, his son Aung Payas Son was the interpreter-bargainer at the craftsman who spoke only Burmese. “The Burmese harp's scale is fixed in C sharp. I wanted mine in G scale. Just getting that across took several weeks.”

It was while coming back to India after paying $300 cargo to get the five harps back that Bhattacharya realised the extent of India's apathy for its own heritage. “No amount of pleading was good as I was charged another Rs 22,000 as customs duty for the harps.”

He shakes his head and adds with a sigh, “The union finance ministry was willing to waive off the 120 percent tax (Rs1.13 crore) on the Ferrari-360 Modeno presented by Michael Schumacher after Sachin Tendulkar equalled Don Bradman's 29 centuries and here nobody was bothered a musical instrument extinct in India being brought back.”

Today, as he traverses the length and breadth of the country at music seminars presenting the harps to Indians, he laments the lack of funding to enable his to spend another three months in Myanmar to perfect the technique.

“I have no funds at all. We hope the government or a patron comes forward to help. Surely culture can't be left out of the India's new 'Look East' policy,” he remarks and adds, “Look at what Satyanarayan GoenkaJi has been able to do, getting back the old vipassana technique from Myanmar to India,” alluding to the original meditative technique created by Gautam Buddha himself which has lasted in Myanmar long after it vanished from India. After Satyanarayan Goenka moved from Mandalay in Burma to India in 1969 he popularised it here too.

Bhattacharya contrasts the government apathy with the largesse of a much smaller country like Cambodia. “They have been able revive an ancient harp which they call peen (a play on the Indian word been) which was almost plucked from a Angkor Wat wall relief by Patrick Kersalé, a French ethnomusicologist who has been encouraged in his work by the Cambodian government. So an instrument which disappeared in the 13th century has actually been able to reappear on the concert circuit there.”

The passionate musician wants to do the same in India.

Will the country step forward and help him?

![submenu-img]() This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...

This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...![submenu-img]() Virat Kohli’s new haircut ahead of RCB vs CSK IPL 2024 showdown sets internet on fire, see here

Virat Kohli’s new haircut ahead of RCB vs CSK IPL 2024 showdown sets internet on fire, see here![submenu-img]() BCCI bans Mumbai Indians skipper Hardik Pandya, slaps INR 30 lakh fine for....

BCCI bans Mumbai Indians skipper Hardik Pandya, slaps INR 30 lakh fine for....![submenu-img]() 'Justice must prevail': Former PM HD Deve Gowda breaks silence in Prajwal Revanna case

'Justice must prevail': Former PM HD Deve Gowda breaks silence in Prajwal Revanna case![submenu-img]() India urges students in Kyrgyzstan to stay indoors amid violent protests in Bishkek

India urges students in Kyrgyzstan to stay indoors amid violent protests in Bishkek![submenu-img]() Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…

Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...

Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet IIT JEE 2024 all-India girls topper who scored 100 percentile; her rank is…

Meet IIT JEE 2024 all-India girls topper who scored 100 percentile; her rank is…![submenu-img]() Meet PhD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary package, was fired within a year, he is now…

Meet PhD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary package, was fired within a year, he is now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman not from IIT, IIM or NIT, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt with AIR...

Meet woman not from IIT, IIM or NIT, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt with AIR...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera

Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera![submenu-img]() Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’

Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Sunanda Sharma exudes royalty as she debuts at Cannes Film Festival in anarkali, calls it ‘Punjabi community's victory’

Sunanda Sharma exudes royalty as she debuts at Cannes Film Festival in anarkali, calls it ‘Punjabi community's victory’![submenu-img]() Aishwarya Rai walks Cannes red carpet in bizarre gown made of confetti, fans say 'is this the Met Gala'

Aishwarya Rai walks Cannes red carpet in bizarre gown made of confetti, fans say 'is this the Met Gala'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...

This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...![submenu-img]() This film had 3 superstars, was unofficial remake of Hollywood classic, was box office flop, later became hit on...

This film had 3 superstars, was unofficial remake of Hollywood classic, was box office flop, later became hit on...![submenu-img]() Meet Nancy Tyagi, Indian influencer who wore self-stitched gown weighing over 20 kg to Cannes red carpet

Meet Nancy Tyagi, Indian influencer who wore self-stitched gown weighing over 20 kg to Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Telugu actor Chandrakanth found dead days after rumoured girlfriend Pavithra Jayaram's death in car accident

Telugu actor Chandrakanth found dead days after rumoured girlfriend Pavithra Jayaram's death in car accident![submenu-img]() Meet superstar who faced casting couch at young age, worked in B-grade films, was once highest-paid actress, now..

Meet superstar who faced casting couch at young age, worked in B-grade films, was once highest-paid actress, now..![submenu-img]() Viral video: Flood-rescued dog comforts stranded pooch with heartfelt hug, internet hearts it

Viral video: Flood-rescued dog comforts stranded pooch with heartfelt hug, internet hearts it![submenu-img]() Dubai ruler captured walking hand-in-hand with grandson in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Dubai ruler captured walking hand-in-hand with grandson in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Virat Kohli drops massive hint on MS Dhoni’s retirement plan ahead of RCB vs CSK clash

IPL 2024: Virat Kohli drops massive hint on MS Dhoni’s retirement plan ahead of RCB vs CSK clash![submenu-img]() Do you know which God Parsis worship? Find out here

Do you know which God Parsis worship? Find out here![submenu-img]() This white marble structure in Agra, competing with Taj Mahal, took 104 years to complete

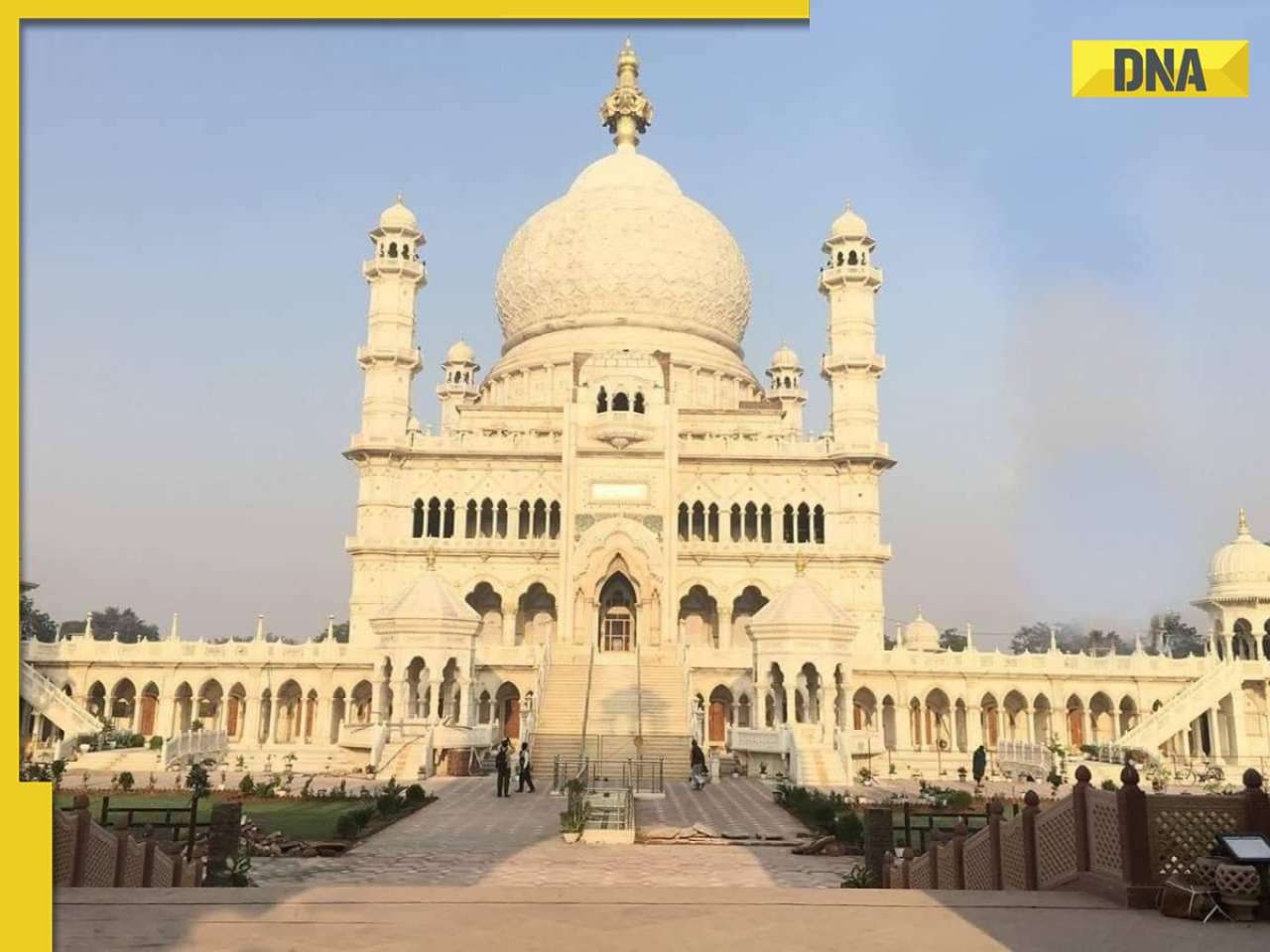

This white marble structure in Agra, competing with Taj Mahal, took 104 years to complete

)

)

)

)

)

)

)