In Lisbon, streets were quiet and many shops and offices were empty, apart from government ones.

The Portuguese have mostly quietly accepted reforms in the labour market, soaring unemployment and cuts to welfare to rein in their debt mountain - but calls to cancel the centuries-old tradition of carnival went a step too far.

The government tried, in the name of austerity imposed by international lenders, to force the end of Tuesday's public holiday but the country effectively shut down all the same as the Portuguese refused to go without their pre-Lent festival.

In Lisbon, streets were quiet and many shops and offices were empty, apart from government ones. Carnival parades went ahead as normal in many parts of the country, some of them adorned with puppets of the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission and European Central Bank - the "troika" of lenders to Portugal's 78-billion-euro bailout.

"Going without the carnival holiday is not going to save the country," said Filipe Garcia, head of Informacao de Mercados Financeiros consultants. "It is on symbolic points that credibility is lost, the government should be more worried about social cohesion than symbolic measures."

It is a timely reminder that despite the so-far tame level of social protest and strikes against Portugal's hardship under the bailout, there are limits to how much austerity the country will stomach during the deepest recession in decades.

As Portugal is the euro zone's second most risky country after Greece, European officials are well aware that any descent by the country into deeper social protest could undermine Europe's argument that Athens' situation is unique. A clear warning sign emerged last week when data showed unemployment reached a record 14% in the fourth quarter of last year - already above the government's estimate of 13.7% for 2012, when the recession is expected to worsen.

"If you include inactive people, unemployment is already above 1 million people, signifying an unpredictable short-term future," said Renato Carmo, sociology professor at the University Institute of Lisbon.

"The government is clearly worried ... there could be a situation of discontent that culminates in more vehement generalised protests."

Those concerns have become more relevant as some economists now fear Portugal will need more funds or be forced to restructure its debts like Athens, which has seen bouts of rioting ahead of finally securing its 130-billion-euro bailout.

The government has ruled out any such possibility, promising to meet tough fiscal goals with sweeping spending cuts and tax hikes, and to carry out painful reforms to boost competitiveness.

"Moan less" Portugal's reform drive includes changes to everything from labour markets to rental laws and cuts to national holidays such as carnival - a religious tradition stretching back 400 years, celebrated with parades and big parties ahead of Lent.

Government ministers, perhaps mindful of the presence of troika officials in Lisbon to carry out their latest review of the economy, repeatedly promised that they would be at their desks on Tuesday.

Missteps by the government, including a suggestion by Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho that people "should moan less" and persist in helping the country overcome its crisis, may have compounded a souring mood in the Portuguese.

"Cancelling holidays is not going to help us in any way, people are just going to be more disappointed and demotivated about their lives," said Rosa Gomes, a 25-year-old shop assistant, who decided to go to work. That frustration appears to be hardening the appetite for protest. The country's largest union, the CGTP, has called a general strike for March 22 after just two such strikes since 2010. The CGTP also gathered an unusually large group of about 100,000 people at a protest this month. Still, analysts say the fact that the Portuguese have little tradition of violent protest gives the government leeway.

"There are no Greek anarchists here, which gives the government time," said Viriato Soromenho Marques, a political analyst at the University of Lisbon. Carlos Fernandes, a 39-year-old civil servant, said anybody who went to work on Tuesday did so "unwillingly".

"This is going to be a long year for us and protests are likely to escalate though I still think we are fundamentally different from the Greeks and will never reach their level of chaos," he said.

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

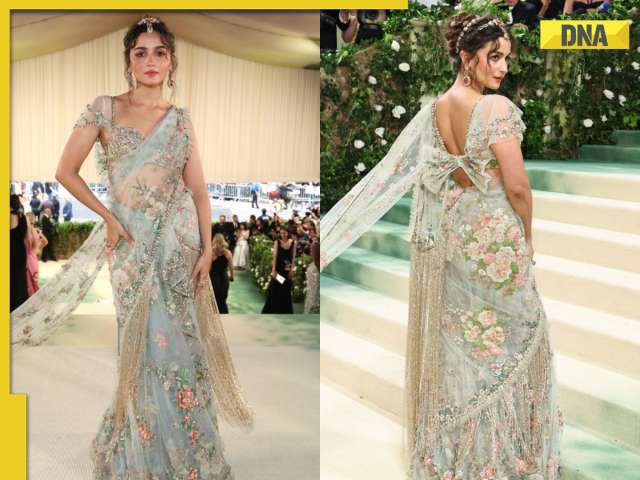

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

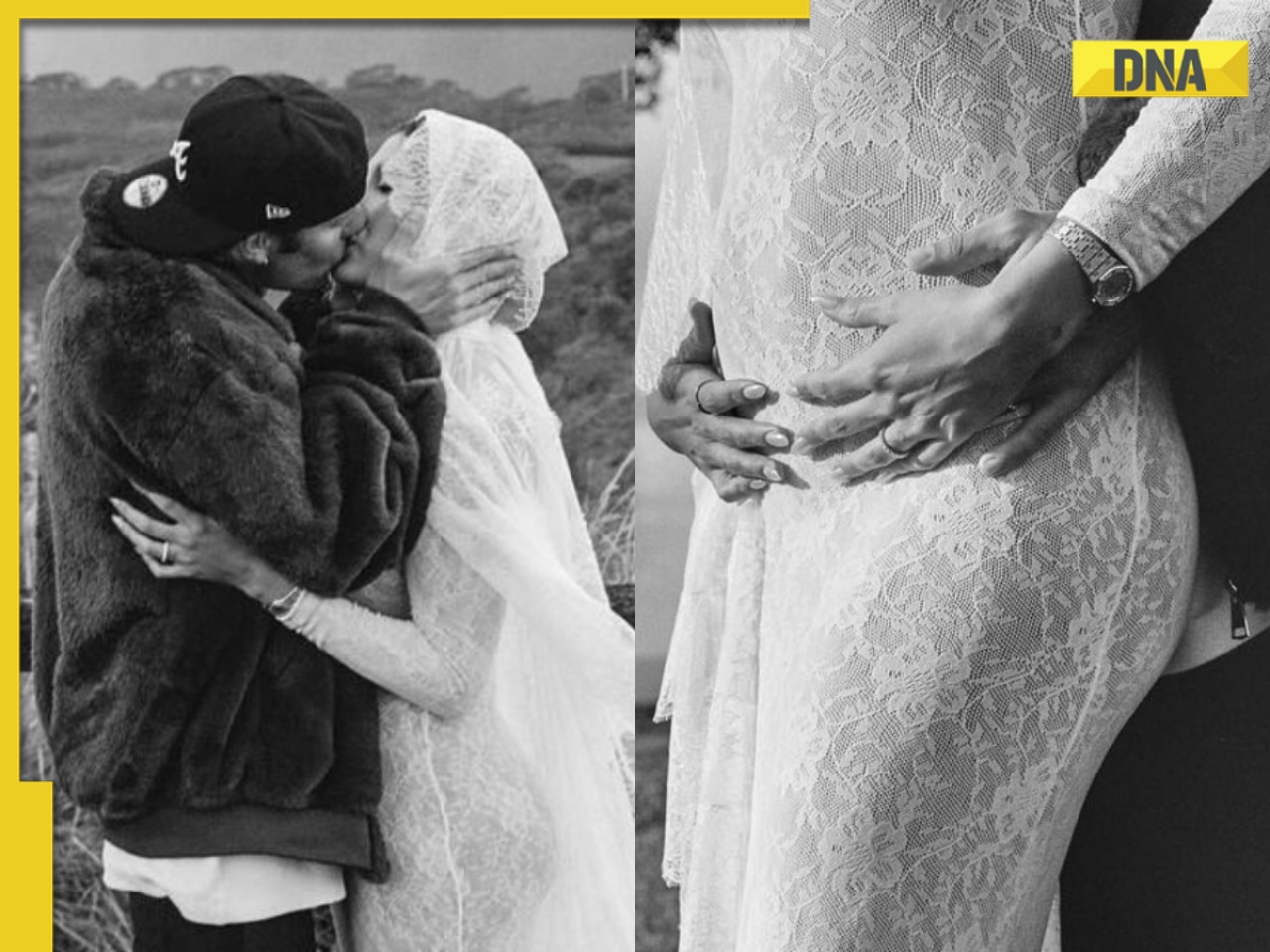

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)