It is generally believed that Sachin Tendulkar failed in critical moments of the fourth innings leading to lots of defeats for India while some others were far better batsmen in such crisis situations. Arunabha Sengupta shows how this assertion is factually incorrect and a result of a cognitive illusion called the Cherry Picking Fallacy.

The look on Sourav Ganguly’s face

Kingston 2002.

It was a series deciding encounter, both teams having won one Test each. West Indies had the better of the initial exchanges, and led by 210 when the Indian first innings ended. Carl Hooper did not enforce the follow on and set India a near impossible target of 408 runs to win.

At tea on the fourth afternoon, India still needed 242 and had lost three of the top order batsmen. However, the team and the supporters had reason to be upbeat. Sachin Tendulkar had already scored 117 at Port of Spain in India’s first win in West Indies in 35 years. But then, he had suddenly seemed to run out of form in the middle of the series, falling repeatedly to the angled deliveries of left-arm pacer Pedro Collins. In this innings, however, the master was striking the ball like a dream. Coming in at the familiar score of 25 for two, he had unfurled his strokes with the zest to win. He had lost Rahul Dravid with the score on 77, but captain Sourav Ganguly had come in to play a perfect foil. The boundaries had screamed off Tendulkar’s bat and by tea he had raced to 82 not out.

As Collins started the first over after the interval, Tendulkar essayed a peach of a cover drive — a stroke that carried a flamboyance more Caribbean than Indian. And then, in the last ball of the over, tragedy struck directly at the Indian hearts. The ball shot through lower than he had anticipated and crashed into his stumps. Tendulkar walked back for a superb 86, and India slumped to 170 for four.

As the rattle was heard, the look on Ganguly’s face told the story. The soaring hopes of a series win came crashing down and disfigured the intensity in the captain’s face into an expression of despair. VVS Laxman was yet to come in, but it was apparent that India had lost their biggest hope of winning the match. In the end they lost by 155 runs, with Ganguly managing 28, Laxman 23.

For most of Tendulkar’s career, well into the 2000s, this was the story of the Indian team. There was hope as long as he was there at the wicket, and everything collapsed with his departure. It was exemplified at Chennai in 1998 against Pakistan, when chasing 270, India managed six before he came in, scrambled up to 254 riding on Tendulkar’s 136, and managed just four more when he left.

However, in spite of his team’s undeniable reliance on the man, what perplexes the mind is the overwhelming belief of his critics that he did not perform in the fourth innings when the chips were down. He failed at critical moments.

This fallacy goes further. People tend to believe that men like Laxman and Rahul Dravid were far more effective in dealing with crisis situations in the fourth innings. After all, there are so many memories of Tendulkar being dismissed and India losing the Test, which could have been saved or won.

On the other hand, we tend to remember Laxman taking India to that incredible win at Mohali against the Australians — that supreme innings that clinched the match by a single wicket. Dravid, well … he did score an unbeaten 70 odd while India won at Adelaide. As one fan recently told me when I asked, “Can’t really recall any other such innings by Dravid off the top of my head, but there has to be many more. After all he was The Wall.”

“Of course, to bat for one’s life we would never rely on Tendulkar who could hardly handle pressure situations. We would need people like Dravid, or that man who can always be trusted to battle the odds” — Steve Waugh.

Cruel numbers

So, first let me place the facts.

Let us analyse the fourth innings of Test matches India has lost in the last few decades. And let us find out how Tendulkar measured against his contemporaries.

Tendulkar has played 26 such Tests, has scored 598 runs in the fourth innings at 23.00 with one hundred and three fifties.

Dravid has batted in 23 such fourth innings, scored 469 at 21.31, with no hundreds and two fifties.

Laxman, in 20 such scenarios, finished with 424 runs at 22.31 with three fifties.

If we bring the other middle-order batsman of their era into the picture, Ganguly featured in 17 such Tests, scored 349 runs at 20.52 with one fifty.

The first surprise is that in such situations too, it is again Tendulkar who heads the table. Laxman actually does not follow him. The man second to Tendulkar in lost causes in the fourth innings is Virender Sehwag, another counterintuitive result. He has 204 runs in the nine fourth innings of lost Test matches, and averages 22.66 with two fifties.

When we consider that a score less than 50 is a failure, the numbers are interesting.

Twenty two of 26 losses have been accompanied by Tendulkar’s failure. For Dravid, it is 21 out of 23, Laxman 17 out of 20, Ganguly 16 out of 17.

Indian middle-order in fourth innings defeats

| Batsman | Inns | Runs | Ave | 100s | 50s | Failure | Failure % |

| SR Tendulkar | 26 | 598 | 23.00 | 1 | 3 | 22/26 | 84.62% |

| R Dravid | 23 | 469 | 21.31 | 0 | 2 | 20/22 | 90.91% |

| VVS Laxman | 20 | 424 | 22.31 | 0 | 3 | 16/19 | 84.21% |

| SC Ganguly | 17 | 349 | 20.52 | 0 | 1 | 16/17 | 94.12% |

The conclusion from the data is that, Tendulkar’s fourth innings failures leading to defeats is at par with Laxman, and less frequent than Dravid and Ganguly. Of course, these numbers do have overlap in which most or all failed together.

Cherry Picking Fallacy

Yet, we tend to think Tendulkar fails more in critical circumstances leading to Indian defeats.

Why is this?

The answer lies in the way we try to approach the question.

We advance with the near confirmed belief that Tendulkar indeed fails in fourth innings. With the objective to confirm this assumption, we try to remember or find examples that show he did indeed fail in such circumstances. Since he is the most discussed player in the media, such instances can be recalled and found quite easily. And we generally ignore the occasions he did not fail.

This is called the ‘Cherry Picking Fallacy’ — where we look at individual pieces of data pointing to a pre-conceived solution, while ignoring the rest of the evidences which show that the truth is slightly different. This is a most common example of Confirmation Bias that we find everywhere in the world.

This is what makes us infer that rock musicians are celebrities. We go by the ones we read about in the papers and ignore the many, many examples of starving souls beyond our ken who will put on impromptu shows for a generous portion of bread and soup. That is why books like ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’ become bestsellers, even when no one really bothers to check the millions who had those same seven habits but did not really amount to much in life. All these are examples of picking and choosing easily available data.

The cherry-picking continues as we progress through our way of thinking. For Dravid, Laxman and the rest, we don’t try and find out the failures as we did for Tendulkar. We try to find the opposite examples — where they succeeded in the fourth innings. Hence we arrive at the wrong conclusion.

Similarly, when looking at successful fourth innings chases, we seldom check and find out that Tendulkar, along with Laxman, is the only Indian batsman to have seen India through to victory with an unbeaten hundred; that Tendulkar with 715 runs at 59.58 with a hundred and four fifties in the 22 innings he has batted in the fourth innings is the highest scorer in that category among Indians. Those are bad cherries for our intuitive beliefs and we generally avoid them.

Okay, in case you are still wondering about the batsman who is the popular choice for batting for one’s life, here is the answer. Steve Waugh played in 13 matches in which he batted in the fourth innings and Australia lost. He scored 170 runs at 15.45 with a highest of 30 not out. There is no fifty in the face of a loss from this batsman who is the one who many believe always fired in crisis situations. In the 31 fourth innings that he batted in his entire career, he managed just two fifties and averaged 25.54.

Intuition can be dangerously misleading.

(Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket historian and Chief Cricket Writer at CricketCountry. He writes about the history and the romance of the game, punctuated often by opinions about modern day cricket, while his post-graduate degree in statistics peeps through in occasional analytical pieces. The author of three novels, he can be followed on Twitter at http://twiter.com/senantix)

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

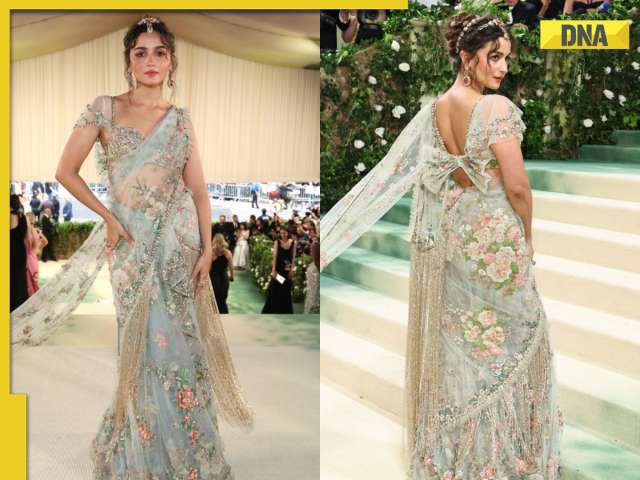

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)