Katherine Rushton in New York investigates the 'moonshot' projects being pursued by mainstream companies to ensure they retain their most creative staff.

Imagine ordering a television or your groceries online and having them delivered to you by an unmanned aircraft. Even Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos admitted it sounds "like science fiction" when he announced that the company is experimenting with a project to do just that. The delivery drones, which will be offered to customers in four or five years' time, stand to transform Amazon's already slick delivery network.

However, the fantastical development serves a much greater purpose than that. It is one of a handful of off-the-wall projects known, in Silicon Valley parlance, as "moonshot ideas": examples of technological developments so ambitious that, before they appear, most people rule them out as impossible.

But America's top technologists firmly believe that they can change the world. Google has been one of the biggest proponents of this kind of thinking. Google Glass, which allows users to search the web or take photographs of what they see through a pair of spectacles, may seem new and outlandish on the surface, but it is already old hat to the company's founders.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin are said to be far more engaged in the company's self-driving cars, which stand to revolutionise the way people travel, or its "Loon" project to deliver broadband to the developing world via balloon. There are doubtless many even more radical ideas, still under wraps. Other technologists don't just want to change the world. They are trying to reinvent it. Peter Thiel, the PayPal founder and billionaire Facebook investor, plans to create a number of artificial islands, independent of any established government, where people could experiment with ways of running society, and with new technology, with none of the regulatory interference which often acts as a roadblock to innovation.

His former PayPal colleague, Elon Musk, has set his sights a little further afield. His Space X company is devoted to colonising Mars. Meanwhile James Cameron, the director of Avatar, has joined Page and Google chairman Eric Schmidt in investing in a company, Planetary Resources, that aims to mine asteroids for fuel and precious metals. Back on Earth, Bezos is spending $42m (pounds 25m) on building an enormous clock, deep in a Texas mountain, which will mark time over the next 10,000 years. It is a folly designed to remind people of the importance of long-term thinking. All of these moonshot ideas serve a similar function: of focusing minds. On one level, they aim to change the world.

On another, more tangible level, they help those companies attract and retain the top-flight engineering talent they require for the more mundane parts of their business. Google is, in essence, an advertising business, but the sheer ambition of its moonshot projects helps to convince staff engaged in tweaking search engine algorithms and selling advertising space that they are helping to change the world. Similarly, Amazon's grand-scale thinking helps it secure top-tier talent to a business whose core function is to stack 'em high, sell 'em cheap.

"The best guys at Google are bored of search, but they're too valuable to lose so it has to give them something to chew on," says Dan Lavin, head of consultancy firm Silicon Valley Ventures. "People go and work for such and such a guy because he had the vision for X. In order to stay, once X is complete, they need the next thing. You can march people to the top of Mount Everest but when you get there …you have to give them something new. You have to march them down to the bottom of the sea."

The effect in Silicon Valley is palpable. Technologists approach their work with the zeal of missionaries. Google's investors may be focused on its climbing share price, but the primary goal of Google's idealistic co-founders is still to advance innovation and convert as many people as possible to their own world view. The use of moonshot ideas is not exclusive to America. In Australia, the text book rental firm Zookal has paired up with a start-up, Flirtey, and is also working on a drone delivery service.

In China, the Southern China Aviation Industry Group has filed a patent for a flying car - a real-life version of the fantastical vehicles which zipped about on screen in Back to the Future 2 or The Jetsons. However, Silicon Valley insiders generally regard Europe and Australia as lagging when it comes to blue-chip technology businesses with such off-the-wall, large-scale ambition. "Moonshot thinking massively sets the US tech industry apart," says Lavin. "Everyone who's good goes there. In Silicon Valley, they're changing the world. In London, they're not, and they don't think they are. They're not even trying to."

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

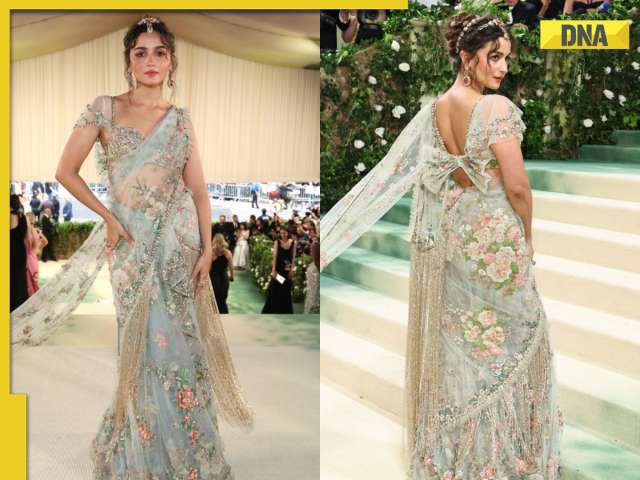

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)