First, the good news — 54 years after it was formed on May 1, 1960, Maharashtra leads the country in industrial proposals received (17.9%) and employment generated (19.8%) between August 1991 and November 2012, beating competitors, such as Gujarat.

Literacy is up at 82.9% in 2011-12 from a measly 35.1% in 1960-61. The number of vehicles in Maharashtra stands at 2.07 crore in 2013 as against 3.11 lakh in 1971 and more than 99% villages are connected by all-weather roads.

Now, the bad news. Agriculture and allied activities account for just 12.4% of the gross state domestic product (GSDP) at current prices in 2011-12 but have a huge share (55%) in total employment. The average size of operational agricultural land holdings has declined from 4.28 hectares in 1960-61 to 1.44 hectares in 2011-12.

The population density in the state, which is among the most urbanised, has increased from 129 per sqkm to 365 in 2011-12, burdening land and resources. The child sex ratio has fallen to 883 in the 2011 census from 946 in 1991. The state's economic survey indicates that 13.1% households have to fetch drinking water from sources far from their houses, 34% households have to defecate in the open and 14.6% have no bathrooms. Ironically, 55.7% households have mobile phones!

So, is Maharashtra a land of contradictions, with cities like Mumbai and Pune standing as islands of development and disparity in an otherwise bleak landscape? Has the state progressed in a lopsided manner after its creation as indicated by poor social indices?

"Our economic planning and ideas of development, which say that economic growth equates development, are to blame. Despite growth, the benefits of development do not reach all people," said senior socialist leader Gajanan Khatu. He added that the British-era wave of industrialisation had focused on cities like Mumbai on the coastline while neglecting inland areas like Vidarbha, a policy carried forward to detrimental effect later. Khatu pointed out that while the focus was on the services sector, manufacturing, which had a massive employment potential was neglected, with job creation taking place only in informal and tertiary areas.

"At the macro-level, the growth rate in Maharashtra is good. However, this is in the MMR and (golden) quadrilateral areas — Mumbai, Pune and Nagpur," said Abhay Pethe, professor, department of economics, University of Mumbai, adding that despite the disparities and inequities, however, the state seemed to be in a comfortable position due to averaging of these figures.

The state's economic survey says that Mumbai, Pune, Thane, Nashik and Nagpur contribute 55.6% to the GSDP.

"Maharashtra is ahead due to existing infrastructure. However, in terms of perceptions... when one talks of governance, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu seem to be inching ahead," he said, adding that around a third of districts in Maharashtra were the most backward in the country.

"Social policies have not been implemented properly. The concentration has been on western Maharashtra, leading to a regional imbalance... if one removes MMR and other areas, Maharashtra's socio-economic indicators seem to be like Bihar," said Pethe.

The Marathi manoos, who proved his fighting spirit by forcing the Centre's hand on the linguistic re-organisation of Maharashtra, has found his position regressing, ironically, despite the presence of two nativist, sons-of-soil parties. Forced out of Mumbai city into the suburbs, and later into the extended suburbs, due to a space crunch and overheated real estate market, Maharashtrians have found themselves to be a minority in the metropolis, with a perception building up that the current model of development has ignored them.

The labour movement, which played a pivotal role in the 'Samyukta Maharashtra' movement, too has been weakened with the engineering and textile industries — which gave Mumbai the status of urbs prima in India — being closed down, accelerating the process of de-industrialisation.

The state, which once produced stalwarts like Mahatma Jotiba Phule, Babasaheb Ambedkar, Justice MG Ranade and Lokmanya Tilak and served as the cradle for major socio-political movements, is being de-intellectualised.

"Presently, there is no academic leadership in higher education. Because of that we have created a mass society in which technological modernity and social traditionality go side-by-side. In such societies, imitation becomes a characteristic," said senior journalist and social historian Aroon Tikekar, pointing out that technological advancements were accompanied by a cultural decline.

"Culture commands a clear commitment to intellect. Culturally, we are going down rapidly because there is no will on part of those who matter to contain the malaise. We are reaching a new nadir every year,"

said Tikekar, pointing out that while research, liberal professions like media and art, literature and commercial and experimental theatre — once the envy of others — were on the decline, there were awards and grants galore! He, however, added that the psyche of the people was changing. "Change has to come in the social minds," said Tikekar.

Farmer leader Vijay Jawandhia pointed out that agricultural development has been concentrated in western Maharashtra while neglecting regions like Vidarbha. He pointed out that while the subsidy for cash crops like sugarcane was high, that for dry land farmers was less.

"For equitable distribution, resources must be devolved more to dry-land farmers who are fighting the vagaries of nature and the market," he said, pointing out that instead of promoting industries in drought-affected areas, the state had focussed on fertile areas like Pune and Kolhapur.

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

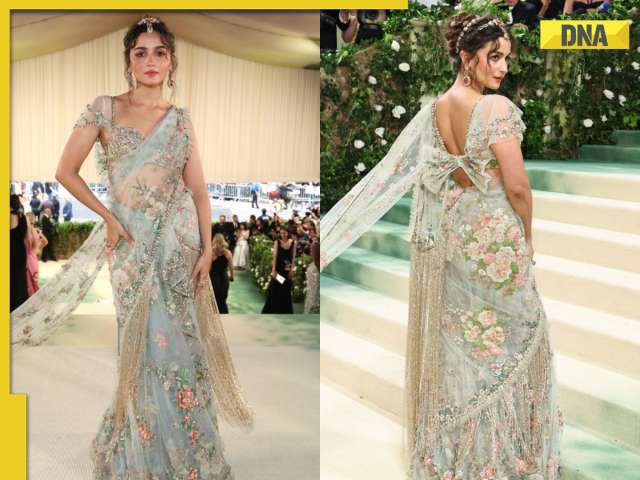

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)