After the recent stay on the possible lift of the ban on dance bars in Mumbai by the state cabinet, Yogesh Pawar met a victim of this archaic morality code who wonders why a state that can't promise her a job can decide what she does for a living.

My first memories are of my mother. I'd be glued to her. Maybe because I was the only one to inherit her light eyes, unlike my brother and sister. She too was very fond of me.

The grace with which she attended to chores like cooking even after a whole day of back-breaking work fascinated me. I'd be happy to run around and gather firewood, fetch water or do anything to help.

We are from the Nat community of traditional dancers and entertainers from Jhunjhunu in Rajasthan. My father's juggling and mother's dancing saw us through as we migrated from village to village. My brother assisted him and my younger sister and I rope-walked or danced.

When you live that kind of life, there is no question of school. Some people had come asking us to enrol but my father ticked them off. "If I send them to school, will you feed us?"

It was 2001. We had gone to a village near Jhalawar where we were performing at a fair. During the break, my sister (the youngest) and my brother asked my father for money to buy a gola. My father, who could never see beyond his son, gave him the money and fobbed off my sister. We suspect it was the bad water in the gola, because he soon fell sick. He had a poor appetite, began looking pale and kept complaining of pain in the stomach. Not knowing better, my parents kept going to local vaids/hakims/healers. By the time they took him to a doctor, who said it was jaundice, it was too late. He died within a week.

My father then got us to Mumbai. We lived near Kalyan in a slum called Shilfata where my father knew another Nat family from our village in Rajasthan. My brother's death had shattered my mother. She would not speak unless spoken to and mostly stayed in bed. Without her, our act suffered and we began going hungry. I must have been 16 or 17 at the time.

Whenever I went out to perform I'd attract lewd comments from men who'd even try to touch me inappropriately.

This led to fights. After one such fight, the Nat neighbour helped calm everyone down and asked my father whether he would send me to a bar to dance. "My own daughter goes there. There is security and she gets a drop home and pick-up. Though dark and just an average dancer, she's earning decently.

Your daughter's fair, light eyed and is a graceful dancer. She'd go places," he told my father.

My father was against it initially. But, I had seen my family suffering and convinced him to let me go. When I first went to the Dombivli dance bar, there was no initial awkwardness — unlike other girls, I'd performed on the street.

Since the bouncers took care of clients who went out of control, I was reassured.

In a week, thanks to my routine, my tip collections began to soar. I would dance solo to the then chartbuster 'Jaan Leva'. When my collections were the highest after a month, Shetty Anna, who managed the bar, asked me if I wanted to shift to a chawl nearby. I couldn't believe it. We who'd lived in makeshift hovels all our lives were moving to a pucca house.

But Anna's generosity led to envy and fights often broke out. Once when I got pushed on the dance floor and fell, a stewardess helped me and we became friends. It was in her company that I first began smoking and drinking. I realised it took the bite out of unwelcome advances from lecherous clients and constant envious slurs from other girls.

Almost a year passed. My father stopped working. In fact, he had gotten hooked to gaanja. While I brought home the money to run the house, my sister was left alone to manage it.

Around this time, because some minister RR Patil wanted dance bars shut, the cops kept raising the hafta.

On one such occasion, Anna refused to pay the new rate and we were raided. I was among the nine taken to the police station.

I will never forget that night. It was like we were the policemen's property. After the inspector lined us up, I was taken to an inner room. Behind the locked door he bit my breasts and forced me to perform oral sex.

When I cried and said I wouldn't, he slapped me and said he would have me killed in an encounter saying I was linked to the underworld.

Many of the others I later learnt were subjected to rape and worse.

I wept all night. The horror of what had happened kept coming back to me. In the morning, Anna came with the money and paid up. We were then let off and Anna dropped us home. On reaching home, I broke down and told my father what had happened. I expected him to tell me not to go to dance in the bar anymore. Instead he said I should forget what happened and think about the family.

I didn't go to the bar for two nights. I kept thinking about what was worse — what had happened to me at the police station or my father's reaction to it. On the third day, instead of expressing remorse, my father began shouting at me for not going to work. He threatened to send my younger sister if I did not go.

Scared for her, I resumed work at the dance bar. But my moves were mechanical. It had hit me that what had happened at the police station could happen again and there was no one I could ask for protection.

This thought began gnawing at me night and day and I began to lose sleep and appetite. My heart was not in the place any more. In our line, despite worries, you can't get dark circles or look listless even if you are worried. I told my stewardess friend who had shifted to a well-known Borivli bar about what was going on and asked her to find me another bar to work in. She not only found me a slot in the same place she worked but was also a source of support in this period when I felt very low.

But raids were common here too. The bar owner had created cavities in the walls and under the table where the girls would be hidden till the cops went away.

Though there were other girls with whom I hid, every time there was a raid, I would start trembling. It was through my stewardess friend I found out that a Thane businessman was interested in me and wanted to take me to his Karjat farm house. I was scared and kept putting it off, though the money being offered was very good.

Travelling from the new bar to my old home was very difficult. Besides, since I had changed bars, the old Anna wanted me to vacate the chawl in Dombivli. When I found another place in a chawl near Dahisar, the owner wanted Rs20,000 as deposit.

I finally realised there was no way out and decided to go to Karjat. I was there overnight. The lovey-dovey talk only lasted till we reached there. The businessman was really roughshod and kept saying that he wanted his money's worth.

I found it all dirty and painful but put up with him thinking of the money I so desperately needed.

My family shifted and I went out with a few more clients to get the house fixed since it was leaking and the walls were damp. I felt proud that despite all that I endured, my family was living in comfort. I was contemplating buying a house when tragedy struck. My sister fled with an autorickshaw driver.

I was distraught and filled with fear for my underage sister and approached the police to file a complaint and look for her. They kept mocking me and bouncing me off. "You are a bar dancer, what do you expect?" I was asked.

The shock of my sister running off like this came as a blow to my bedridden mother who took it to heart.

She'd keep calling out her name and died in a week. Now it was only me and my father.

Apart from dancing at the bar, the task of managing the home also fell upon me.

Two years later, my sister returned from Azamgarh in UP where the rickshaw driver had taken her. Her "husband" had abandoned his three-month pregnant wife. I had half a mind to tell her to go away. But the bruises on her once beautiful but now weary face and how vulnerable she looked made me break down and I took her in.

The bars have since shut and girls like me have been pushed into dhanda.

I hear the courts have said the bars might reopen now. But what about those like us who were forced to become commercial sex workers from dancers because of the government's decision? How is this any better than mere dancing in a bar? RR Patil went after dance bar girls, but does he realise how thousands of waiters, stewards, stewardesses, sweepers and others who worked at these bars were also left jobless and their families put out to pasture? It's not like the government is giving us jobs, is it?

I have been walking the streets of Colaba and Fort for the past few years. Even if the bars reopen, I know I cannot go back there. I have tied up with a syndicate of eunuchs who manage the area by paying off the cops.

Recently, when a client began insisting on unprotected sex and said he'd pay me less if I insisted on it, I told him to get lost. "Don't forget you are a prostitute, don't act so pricey," he said while going. I called out after him, "I'm here to do dhanda on my terms. You pay me what I ask upfront and wear a condom when I tell you, or f&*k off."

Now, when someone calls me randi, chhinaal or something like that, I laugh. Earlier I'd get hurt and angry but now it doesn't bother me. I'm not asking these people to feed me. Just like them, I'm supporting my family single-handedly by working very hard. If they take pride in that, why shouldn't I?

I have learnt to speak basic English and dress in Western clothes often.

These days the men want women like that. Even if they are smelly, look like pigs who haven't bathed in days and fart during sex, the woman has to look good.

I'm 31. If I married, I'd have loved to have a child, cook, and run my home but that is not my fate. I can't dream of that now. Not when my sister's son is going to school and my father's bedridden.

Figures of dance

A 2005 study conducted by the Research Centre for Women's Studies at SNDT University along with the Forum Against the Repression of Women found that many bar dancers were illiterate, and most barely knew skills other than dancing. The study also found that the women were not forced to dance but took to it as a matter of choice, and that many belonged to traditional dancing communities. Many were married, and about 62% were sole breadwinners in their families

The study also revealed that most bar dancers earned between Rs 5,000 and Rs 1 lakh per month; with only 30% earning less than Rs 10,000.

A post-ban study conducted by Tata Insititute of Social Sciences revealed that 92% of them were willing to avail of government schemes for employment, education of their children. But in the absence of any such scheme, most of the dance girls migrated to other places and took to prostitution.

When the Bill to ban dance bars in Mumbai came into force in July 21, 2005, there were more than 1000 dance bars in the city alone, of which 307 dance were registered, while the others operated illegally. An estimated 650 dance bars existed in Maharashtra. The ban affected the livelihoods of more than 1,50,000 people employed in these bars, including 75,000 bar girls.

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

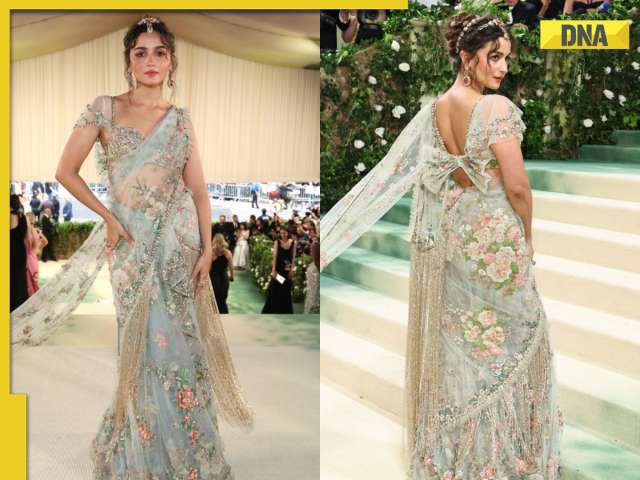

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)