The process of elections in Indian political parties has unmitigated disaster written all over it

Back in 2014, Rahul Gandhi, next in line to be the Congress president, unapologetically told a news channel that he was “absolutely against the concept of dynasty”. By September 2017, however, faced with a poser from a student gathering in Berkeley, Gandhi could only offer a grudging acceptance of dynasty as his answer.

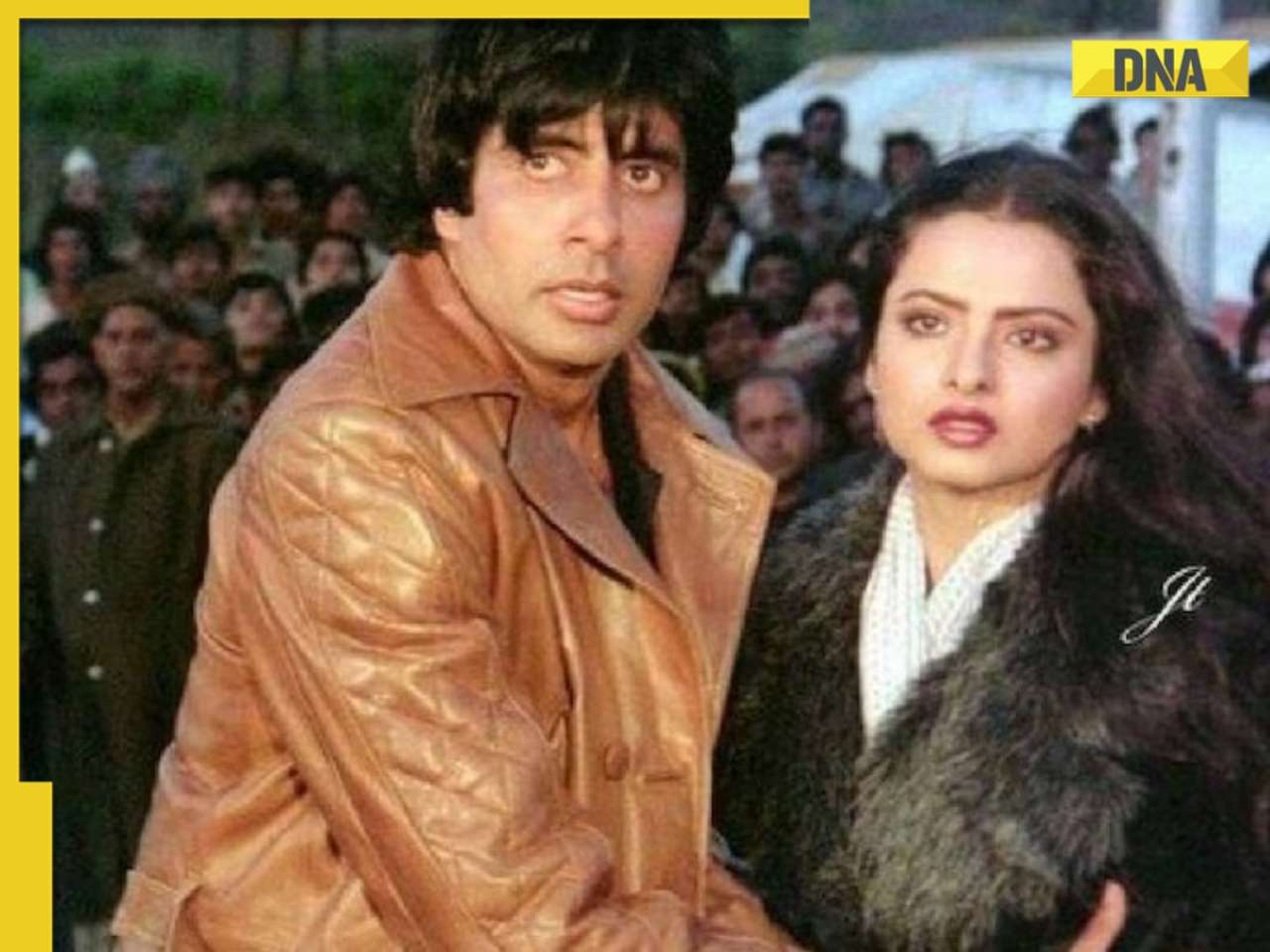

“Most of the country,” he said, “runs like this, so don’t go after me, Akhilesh Yadav is a dynast, Mr Stalin is a dynast, Mr (Prem Kumar) Dhumal’s son is a dynast, so don’t just go after me. Even Mr Abhishek Bachchan is a dynast, also Mr Ambani, that’s how the entire country is running,” he said.

Not one to let go of easy pickings, the BJP latched on to Rahul’s statement and deftly mined it, projecting Congress as a party woefully lacking in internal party democracy. What remained largely unsaid in the ensuing media onslaught was that the BJP is not big on intra-party democracy either. In fact, a number of national as well as state parties fail miserably when tested on the touchstone of inclusiveness and decentralisation of party decision making.

The failure in the measure of internal democracy is equally disastrous, stemming from a rather deliberate laxity on two fronts: First, internal elections continue to be sham affairs, shrouded in mystery and mostly a closed-door event. Second, the nomination process remains arbitrary, with parties dithering on chalking out detailed primers on members’ nomination.

Regulatory landscape

In India, any association or body of individuals wanting to register itself as a political party has to apply to the Election Commission (EC). Once registered as per the Representation of the People’s Act, 1951, the party is required to conduct internal elections as per Section 29A (9), which mandates that any change in political party’s name, head office, office bearers, address, or in any other material matter, shall be communicated to the EC without delay.

Despite this statutory provision, parties repeatedly fail to file the requisite details. More often than not, the docket on internal elections furnished by the parties is woefully inadequate. Important details such as the name and designation of the delegates, the total number of voters, the nature of the election, name of the contenders, if any, and votes polled for them are completely absent. Irrespective of the age of the party or its national or regional character, almost all parties in India follow dismal levels of internal democracy.

For instance, in May 2016, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) furnished an affidavit to the EC, specifying that all 25 members of its National Executive were elected “unopposed”. AIADMK held an election for the post of general secretary in May 2015 but failed to mention the names, number or designations of delegates present for the elections. The affidavit conveniently mentioned that since “no one except chief minister J Jayalalithaa had filed the nomination papers”, she had been elected unanimously.

In case of the All India Trinamool Congress, the number of delegates attending the election of the chairperson was mentioned sans any reference to their positions within the party or the manner in which the poll was conducted. Mamata Banerjee, who formed the party, keeps getting “elected” as its leader in 2001, 2006, and 2011.

In an affidavit furnished in November 2014, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) failed to mention the term for which its functionaries were elected or the next date of election, the number of delegates present or their position and the nature of the election.

Track record of other national parties such as the Congress, BJP, or the RJD is no better. Rahul is all set to be the next Congress president as all 89 nomination papers filed for the party presidency proposed his name alone, effectively making a mockery of the poll process.

Botched experiment

Ironically, Rahul is the only politician who can claim credit for attempting to infuse a semblance of internal democracy in Indian politics. Building up to the Lok Sabha elections of 2014, Rahul announced that the Congress will hold American-style primaries for 16 constituencies, so that a system that “allows for a broader participation of party supporters in deciding who should be a candidate from their constituency” could be evolved. The Congress then boasted that it was the first national party to bring in such a process to make the “ticket allotment process fair and transparent”.

The ground reality, however, was quite disappointing as incumbent MPs, senior leaders, or their family members were elected in the 16 constituencies. Additionally, in states such as Delhi, Maharashtra, MP, and Karnataka, charges ranging from the selection of constituencies to bogus voting or use of money were levelled against the party leadership.

Also, once the experiment started, senior leaders were up in arms. Chandni Chowk, represented by Kapil Sibal, and northwest Delhi, represented by Krishna Tirath, were chosen for primaries but the decision was soon reversed after the two protested. Finally, the constituencies of New Delhi and northeast Delhi were picked for the primaries. The incumbents on the two seats — Ajay Maken and Jayprakash Agrawal — had a walkover. Nobody competed against Maken while the contender running against Agrawal secured 47 votes against his 252.

Impact on Indian polity

The 170th report of the Law Commission of India was prescient in that it could see that the goals set out in the Preamble of the Constitution could be achieved only if political parties succeeded in fine-tuning their internal democracy. “A political party that does not respect democratic principles in its internal working cannot be exposed to respect those principles in the governance of the country. It cannot be a dictatorship internally and democratic in its functioning outside.”

“If democracy and accountability,” the report continued, “constitute the core of our constitutional system, the same concepts must also apply to and bind the political parties that are integral to parliamentary democracy. It is the political parties that form the government, man the Parliament, and run the governance of the country. It is, therefore, necessary to introduce internal democracy, financial transparency, and accountability in the working of political parties.”

Even the Second Administrative Reforms Commission (SARC), 2008, obliquely indicated that the Indian political scene could ward off over-centralisation of power and corruption by encouraging internal party democracy. “A factor that increases corruption is over-centralisation,” the SARC, 2008, stated.

Meanwhile, the nomination process continues to be marred by an arbitrary exercise of power and there is little rationale behind handing out of tickets, except the perception of a candidate’s winnability. In their seminal work, ‘Incumbency, internal processes and renomination in Indian parties’, A Farooqui and E Sridharan highlight that the criterion that determines whether an aspirant will be given a ticket or not is “merit”, which is a holistic judgement on current victory prospects. Another general rule of thumb followed is the sitting-getting principle, which is to say that incumbents get the nomination unless they are perceived to be no longer likely to win.

NOMINATIONS IN THE US

The United States (US) has a jump-start of 118 years, when it comes to making the internal party elections a true representation of the people’s choices. It was in 1899 that the first statewide primary election was held in Minnesota, which was aimed at undercutting the clout of the party leadership. Unlike India’s arbitrary and centralised nomination dynamic, primaries elections are conducted in the US by government officials using public funds and under the established public law, and not by party officials using party funds and under party by-laws.

Any person interested in seeking a Democratic or Republican party nomination has to make an application for an elective office.

The application must be signed by a legally mandated number of voters from within the jurisdiction. On the ballot paper, the names of all candidates for different offices are specified and voters mark their candidate preferences for different offices.

Individuals with the most number of votes are confirmed as the party’s nominees, who then go on to contest the general elections.

For presidential elections, the Democratic and the Republican parties nominate their presidential candidates at their conventions, which is attended by delegates picked as per the party by-laws.

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)