If the law permits repression, the populace would only be too glad to abide by it.

Can ostensibly “secular” laws have communal underpinnings? Can tolerance be judicially enforced, and in such a process, does such enforcement not demonstrate inherent intolerance? And, as Herbert Marcuse provocatively asked in his 1965 essay “Repressive Tolerance”- doesn’t one of the paradoxes of liberal societies arise from this very commitment to tolerance? A society committed to respecting the viewpoints and customs of diverse people within a pluralistic society inevitably encounters this challenge: will it tolerate those who themselves do not agree to respect the viewpoints or customs of others? Paradoxically, the liberal commitment to tolerance requires, at some point, intolerance for those who would reject that very commitment.

These questions arise in the wake of a concerted effort by Jain monks of Palitana in Gujarat’s Bhavnagar District, to have the entire town declared as a vegetarian zone- where the sale and consumption of meat and eggs shall be illegal, and any kind of animal slaughter, especially that of cows, shall be visited with strict legal penalties. Elsewhere, in Mumbai, one lives in trepidation of communal clashes breaking out just before Bakri Eid, when members of certain cow-protection groups, aided and abetted by residents of certain areas, impound legally certified cattle which were on their way to abattoirs, and delegations of representatives of the Jain community demanding that police stop the entry of cattle into the city limits.

In fact, in October last year, a riot was averted in Agripada when a belligerent mob of 100, comprising members of the Bajrang Dal and assorted go raksha sangathans went on a rampage and could be stopped only with the intervention of the police and the local mohalla committee. Under directions of the Bombay High Court, a committee was set up under former police commissioner Julio Rebeiro to find a permanent solution. Rebeiro submitted his report and recommendations in August 2013, but the government has remained apathetically inactive.

It is trite that religious majoritarianisms, and its offshoots- cultural as well as culinary, are at play here. But what allows its purveyors to run amok and quite successfully at that? The answer lies in the laws dealing with town planning, animal protection, policing, bolstered by certain judgements of the Supreme Court.

First, the Bombay Provincial Municipal Corporation Act, 1949 as extended to Gujarat, Section 466 (1) (D) (b) of which allows the city or town Commissioner to prohibit and enforce the closure and opening of slaughterhouses and shops selling meat products, either cooked or raw.

Second, the Bombay Animal Preservation Act, 1948 which prohibits the slaughter of animals useful for milch, breeding or agricultural purposes. This Act was extended to Gujarat by the Bombay Animal Preservation (Gujarat Extension and Amendment) Act, 1961, and amended in 1994 by the Bombay Animal Preservation (Gujarat Amendment) Act, 1994.

Third, Sections 33(1)(m) and 33(1)(w)(2) of the Bombay Police Act, 1951 which permits the forced closure of shops and establishments for the maintenance of law and order.

All challenges to these provisions have been based not on grounds of religion, but on the premise of the fundamental right to one’s freedom of trade and profession. Of course, those resisting the challenge made it a battle between livelihood and their own values of purity and piety- because the cow in India is indeed “holy”. But, the judiciary entrusted with protecting and upholding secularism, which definitely involves tolerance for diversity, has evolved and sanctioned a model which is oppressive in the extreme.

How does this work out in the jurisprudential sphere- that laws which apparently have no overt religious colour and are meant for “general welfare”, or to uphold “public interest” end up being interpreted in a manner which place an onerous burden on minorities? It begs a further question- can one say with certitude that such legislations are entirely devoid of religious, and majoritarian underpinnings?

In Braunfield v Brown (1961), the Supreme Court of the United States had to decide whether a Pennsylvania law prohibiting the sale of retail products on Sunday violated the freedom of religion of Orthodox Jews because since they observed the Sabbath on Friday evenings and Saturday, they were effectively being compelled to cede grounds to competing Christian merchants. By a 6-3 majority, the court rejected the challenge, but Justices Brennan and Stewart’s dissent ring out loud.

Especially, Justice Stewart’s: “Pennsylvania has passed a law which compels an Orthodox Jew to choose between his religious faith and his economic survival. That is a cruel choice. It is a choice which I think no State can constitutionally demand. For me this is not something that can be swept under the rug and forgotten in the interest of enforced Sunday togetherness. I think the impact of this law upon these appellants grossly violates their constitutional right to the free exercise of their religion.” (Emphasis, mine.)

In India, and regarding Palitana in particular, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Hinsa Virodhak Sangh (2008) invites ones attraction. Since 1993, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation had banned the sale of meat for nine days of the Jain’s Paryushan festival, and over the years, nine was stretched to eighteen. Justice Katju delivered a sobering sermon on tolerance and diversity- “since India is a country of great diversity, it is absolutely essential if we wish to keep our country united to have tolerance and respect for all communities and sects.”

So far so good. Then came the judicial decree of enforcing such tolerance- since the Jains form a sizeable share of the population, others must perforce cede ground out of a spirit of tolerance and make peace with temporary deprivation of livelihood and compromise on exercising culinary and nutritional choice. But why couldn’t this so-called tolerance be exercised by those asserting their freedom of religion? Note the use of the term “sizeable” and consider the clout and pelf it enjoys with the government. No prizes for guessing in whose favour the scales shall be tilted.

Not that the judgement was based entirely upon an interpretation and discourse on faith and religious sentiments. It was also quite an educative lesson in animal husbandry, since it drew glowing references to the decisions of constitution benches in the Jan Mohammed Usmanbhai and Mirzapur Moti Kureshi Kassab cases wherein the indispensability of cows and even cow urine to the Indian economy received judicial recognition.

Emboldened by, and borrowing from the courts’ empathy for the pitiable plight of the holy cow, the movement in Palitana goes under the moniker of Palitana Jiv Raksha Abhiyan, and in order to drive out the “violence” of animal slaughter, the monks and their followers have magnanimously announced that all butchers will be “rehabilitated “at an estimated cost of 2 crores which is peanuts compared to the 700 crores spent annually on the maintenance and upkeep of their temples and sanctity of their religious values.

The movement in Palitana is not a fresh development- since 2012 it has only been growing in strength. The Collector of Bhavnagar says that legal opinion shall be sought before implementing any ban. But, with the force of judicial precedent on its side, a government does not have any reason to be stymied in exercising and enforcing discrimination. It is all about legally sanctioned “tolerance”, you see.

![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…

Haldiram may get Rs 425790000000 offer soon, world’s biggest PE firm planning to…![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link

TN SSLC 10th Result 2024: Tamil Nadu Class 10 results DECLARED @ tnresults.nic.in, here's direct link![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch

Yodha OTT release: Sidharth Malhotra, Disha Patani's hostage rescue drama releases online, here's where you can watch![submenu-img]() Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet

Meet Aastha Shah, influencer with skin disorder, was bullied, set to break boundaries by walking Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone

Meet actress who confirmed divorce, removed all photos with husband from Instagram, not Deepika Padukone![submenu-img]() Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others

Actress Laila Khan's step-father Parvez Tak found guilty of murdering her and five others![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos

Justin Bieber announces wife Hailey's pregnancy, shows off her baby bump in heartwarming maternity shoot photos![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: Punjab Kings knocked out of playoffs race after 60-run defeat to Royal Challengers Bengaluru ![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL

PBKS vs RCB: Virat Kohli scripts history, becomes first batter to achieve this record in IPL![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs CSK IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings

GT vs CSK IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() ‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral

‘Ataichi leke baitha hua hai’: Virat Kohli, Mohammed Siraj troll RCB teammate during ad shoot, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet

Watch: Women's epic dance to Sapna Chaudhry's 'Teri Aakhya Ka Yo Kajal' on Amsterdam's street wins internet![submenu-img]() Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned

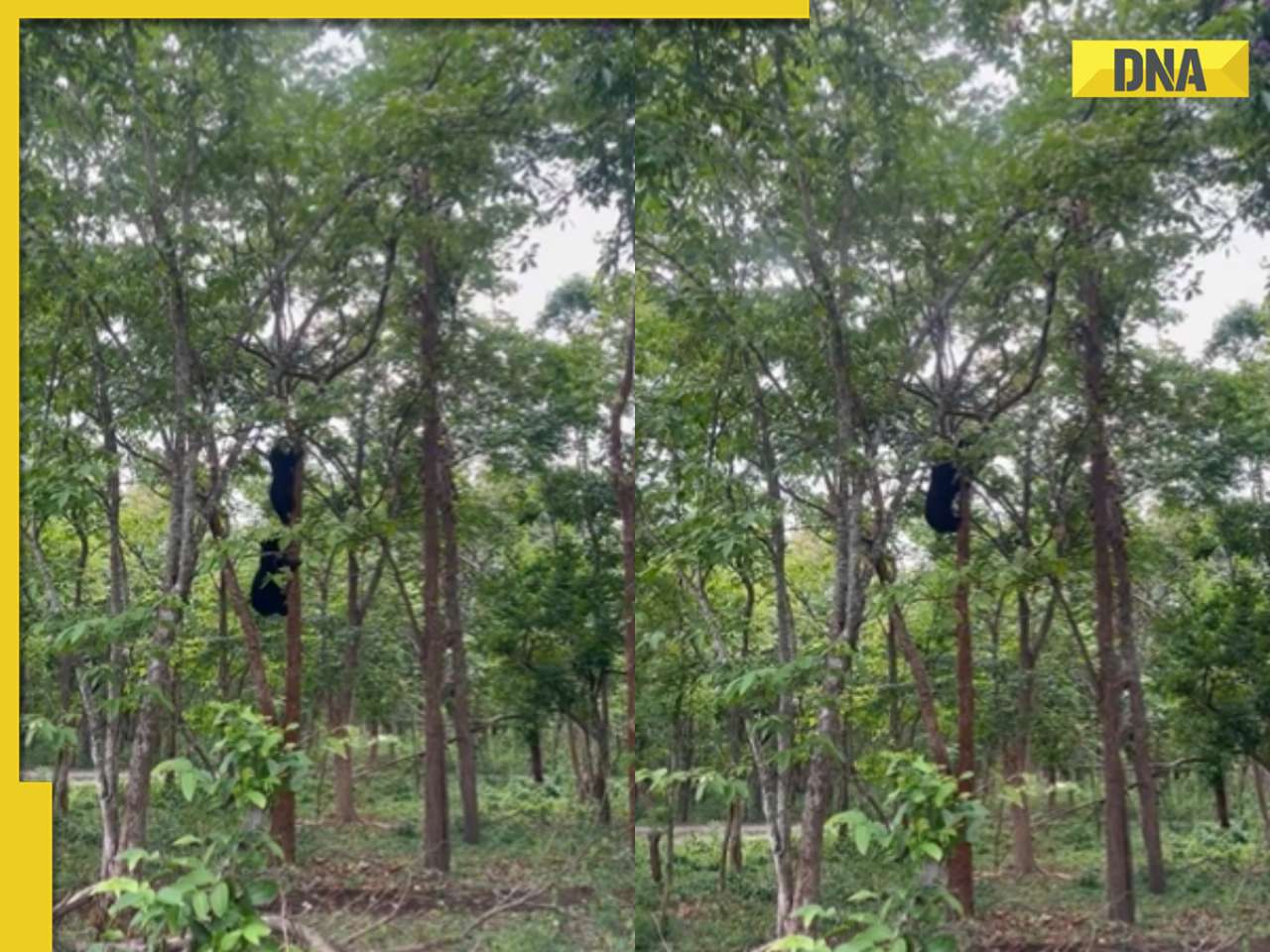

Ever seen bear climbing tree? If not, viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...

This Indian King bought world's 10 most expensive cars and converted them into garbage trucks due to...![submenu-img]() Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral

Pakistani college students recreate Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's pre-wedding festivities, video is viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

Viral video: Brave mother hare battles hawk to protect her babies, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)