alavika V, Damini K Gowda, Pranam B, Siva S, all of whom are between the ages of 10 and 14, are currently some of the best known swimmers and have made headlines at the recently concluded Junior and Sub-junior National Aquatic Championships held in Bangalore.

However, there is uncertainty over whether these swimmers will go on to represent the state and the country at senior and open category meets, over the next couple of years.

The past has seen very few swimmers who have consistently maintained high-quality performances all through their sub-junior, junior and senior age-groups — in a career that would span a decade.

Take for instance, Yudisthir Jai Singh of Maharashtra. He holds national records in the 50m and 100m freestyle and 50m backstroke. They were set in 2005 when he was swimming in the group IV category (sub-junior).

Five years on, and the swimmer has disappeared off the national circuit. There could be several reasons for that like education taking precedence, financial backing running out, or even physical burn out (some thing a lot of swimmers who perform from a very young age face.)

So what is it like for the coaches, who specifically train the sub-junior and junior swimmers, and are aware that there is a distinct possibility of their budding sportsters giving up the sport altogether?

It’s a question most of them answer with a sigh.

“The whole system has to change and this includes the system we follow in sports, and even education,” says Pradeep S Kumar, a national swimming coach, who has trained swimmers from different age groups for the last 25 years at the Basvangudi Aquatic Centre.

“We put a lot of time and energy into a swimmer. It’s not just the coach, but the whole support staff that backs a swimmer’s training programme and to see them quit at an age when they actually need to start performing is very disheartening. Over the years, we have lost several top swimmers who chose academics over the sport and we continue to lose good swimmers, even today,” he says.

Sadly, this is the case across sport. Seldom do top performers in the under-14 and under-16 categories go on to take up sports seriously once they enroll into a professional course or even degree courses.

And what’s worse, the system in Karnataka does not even monitor a sportsperson’s performance once they have been given a seat through the sports quota, unlike universities abroad or even universities in neighbouring states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, where apart from marks, performers at university meets, national and international level tournaments also get stipend for representing college teams at various national meets.

“We hardly get any incentives like sportsmen in the Kerala or Andhra Pradesh education system do [where five percent grace marks are given to the performers]. In the first year of college I was told it was compulsory to represent the college but after that it’s just one’s own interest and the support we get from our respective departments,” says Shalini Prakash, a former junior national and all-India university medalist in Badminton. Prakash earned a sports quota seat in engineering through the Common Entrance Test (CET) and graduated from RV College of Engineering in Bangalore.

“Sports people will continue to quit once they get a seat in professional courses unless the CET makes it mandatory for them to perform all through their course,” says Dr Shivarama Reddy, of Visvesvaraya Technological University (VTU).

Often, those sports people who decide to take up professional degrees are left in a fix to choose between their studies and their sporting career. And this trend is likely to continue unless the education system wakes up.

Reddy puts things into perspective: “Most of them take the benefits of the sports quota and then forget all about sports. There is very little the colleges can do about this. Either the parents discourage their children from pursuing sports and ask them to concentrate on studies, or there is absolutely no support from colleges. Though the VTU gives cash incentives every year to top performers at the University Nationals, only a change in the CET mandate can really make a difference and ensure that all colleges fall in line and support those students who enter through the sports quota. Only then will the trend change,” says Reddy who is also the physical education director of BMS Engineering College.

Often it is the sports directors at colleges who take an interest in developing sports and backing an already-established sportsperson’s career with the necessary requirements like attendance, scholarships, financial benefits and supporting a sportsperson’s education with special coaching classes ahead of board exams.

“At Jain University, we have about 220 students in the sports department and all of them participate at different levels like state, national and international. When we have this kind of strength in the department, it becomes very important for us to get the support of lecturers and principals,” says Shankar UV, the sports director of Jain University.

However, out of 160 Engineering colleges in the state, only about 40 have a designated Physical Education director. It is a similar case in several degree colleges across the state too. And as long as they do not have a person in charge of sports in schools and colleges the sporting scene will not improve, feels Sunder Raj Urs, former director of physical education at Bangalore University. “Who will the students who are pursuing sports turn to if they don’t have a proper system in place? Nobody cares for sportspeople,” says Urs.

Though there were talks about introducing a credit system for sportspeople who have won medals at national events, it has not been implemented by the state government. Even a committee formed by Prof Vaidhyanathan, during Basavaraj Horahatti’s tenure as education minister, suggested providing incentives like awarding grace marks and cash awards, apart from formulating a directorate for Physical Education and appointing Physical Education teachers for schools and colleges. The government has yet to implement it.

“In the committee report we have briefly mentioned the requirement of introducing grace marks and cash awards for sportspersons from the school level. It has been implemented at the school level to a certain extent but it’s not known why it has not been introduced at the PU board,” says Urs, who is also a member of the Prof Vaidhyanathan Committee.

Srinivas Murthy, head coach for basketball at the Jayanagar Sports Club, on the other hand, indicates that balancing both academics and professional sport puts a lot of pressure on youngsters.

“I can’t expect a player to spend seven hours on court training when they are already burdened by studies. With all the semester system, it’s just a lot of pressure on the kids too because of which the transformation of junior players to seniors has come down drastically. There is absolute lack of encouragement from schools and colleges,” says Murthy.

Apart from a lack of support from the educational system, pursuing sports as well as attaining a professional course degree is a personal choice, says Srinand Srinivas, who maintained a consistent form in swimming, despite taking up a medical seat at Bangalore Medical College.

“When a sportsperson decides to do both – studies and sports -- then they totally need to sacrifice their social life. It’s not too hard to balance both studies and sports as long as you have got your priorities right. I have seen a lot of youngsters quit because they can’t find free time to relax, go out and have some fun,” says the international swimmer.

![submenu-img]() MBOSE 12th Result 2024: HSSLC Meghalaya Board 12th result declared, direct link here

MBOSE 12th Result 2024: HSSLC Meghalaya Board 12th result declared, direct link here![submenu-img]() Apple iPhone 14 at ‘lowest price ever’ in Flipkart sale, available at just Rs 10499 after Rs 48500 discount

Apple iPhone 14 at ‘lowest price ever’ in Flipkart sale, available at just Rs 10499 after Rs 48500 discount![submenu-img]() Meet man who left high-paying job, built Rs 2000 crore business, moved to village due to…

Meet man who left high-paying job, built Rs 2000 crore business, moved to village due to…![submenu-img]() Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...

Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...![submenu-img]() Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'

Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

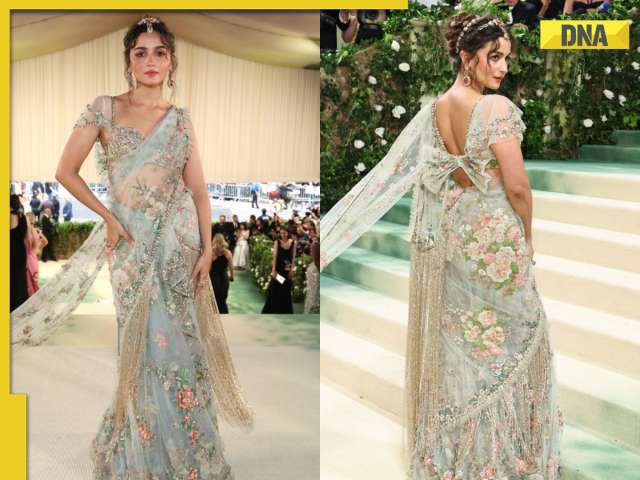

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...

Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...![submenu-img]() Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'

Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'![submenu-img]() This superstar was in love with Muslim actress, was about to marry her, relationship ruined after death threats from..

This superstar was in love with Muslim actress, was about to marry her, relationship ruined after death threats from..![submenu-img]() Meet Madhuri Dixit’s lookalike, who worked with Akshay Kumar, Govinda, quit films at peak of career, is married to…

Meet Madhuri Dixit’s lookalike, who worked with Akshay Kumar, Govinda, quit films at peak of career, is married to… ![submenu-img]() Meet former beauty queen who competed with Aishwarya, made debut with a superstar, quit acting to become monk, is now..

Meet former beauty queen who competed with Aishwarya, made debut with a superstar, quit acting to become monk, is now..![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Abishek Porel power DC to 20-run win over RR

IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Abishek Porel power DC to 20-run win over RR![submenu-img]() SRH vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Here’s why CSK star MS Dhoni batted at No.9 against PBKS

IPL 2024: Here’s why CSK star MS Dhoni batted at No.9 against PBKS![submenu-img]() SRH vs LSG IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Lucknow Super Giants

SRH vs LSG IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() Watch: Kuldeep Yadav, Yuzvendra Chahal team up for hilarious RR meme, video goes viral

Watch: Kuldeep Yadav, Yuzvendra Chahal team up for hilarious RR meme, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Not Alia Bhatt or Isha Ambani but this Indian CEO made heads turn at Met Gala 2024, she is from...

Not Alia Bhatt or Isha Ambani but this Indian CEO made heads turn at Met Gala 2024, she is from...![submenu-img]() Man makes Lord Hanuman co-litigant in plea, Delhi High Court asks him to pay Rs 100000…

Man makes Lord Hanuman co-litigant in plea, Delhi High Court asks him to pay Rs 100000…![submenu-img]() Four big dangerous asteroids coming toward Earth, but the good news is…

Four big dangerous asteroids coming toward Earth, but the good news is…![submenu-img]() Isha Ambani's Met Gala 2024 saree gown was created in over 10,000 hours, see pics

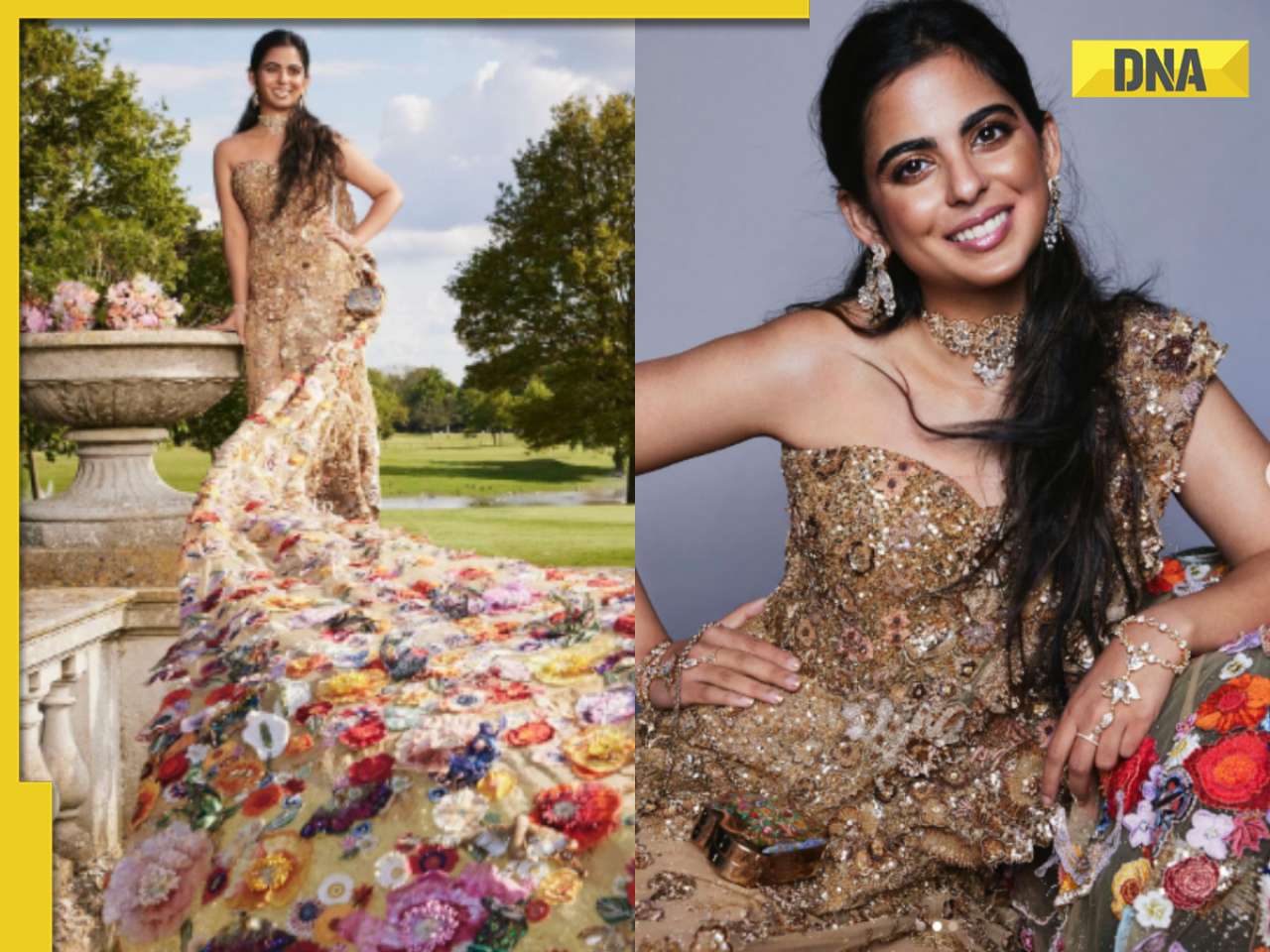

Isha Ambani's Met Gala 2024 saree gown was created in over 10,000 hours, see pics![submenu-img]() Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...

Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...

)

)

)

)

)

)