Sachin Tendulkar has earned this very special extra chunk of immortality by his dedication, fitness and intelligence, writes David Frith

Cricket is full of surprises. But it really and truly is almost beyond belief that a cricketer can chalk up one hundred scores of 100 or more in international matches.

In 1895, when that bearded giant Dr WG Grace of Gloucestershire and England notched his 100th first-class century, people assumed that this achievement would forever remain unique. But they were wrong: since then, as many as 24 other batsmen have made 100 or more first-class centuries.

When Don Bradman, Australia’s supreme batsman, retired in 1949 with 29 Test centuries to his name (in only 52 Tests), that figure too seemed certain to remain unchallenged, for nobody then could have foreseen the massive expansion of Test cricket.

And when one-day internationals began to proliferate in the 1980s and ’90s, even then no sensible person could possibly have imagined a batsman piling up over 18,000 runs in the 50-overs format.

Now, though, we are slowly digesting the fact that a wonderfully fit and sharp-eyed little batsman from India, touched by genius, has reached three figures 100 times while batting for his country. If only I had put a few pounds/dollars on that likelihood twenty years ago. A bookmaker would surely have given me astronomical odds.

Sachin Tendulkar has earned this very special extra chunk of immortality by his dedication, fitness and intelligence. Perhaps, he is aware that all that remains beyond his playing career is the everyday routine of enjoying family life, marketing his name and perhaps doing good deeds, so he has decided not to leave the game he loves and adorns until his powers have irretrievably waned. “You’re a long time retired” goes the old saying.

Batsmen once played on into their forties as a matter of course.

The obsession with youth in recent years has cut short many a cricket career before its time. Indeed, only two years ago it seemed that Sachin Tendulkar was very close to retirement. Injuries and surgery have shortened many careers. We now know that he was merely heading off into a further lap. How many might there be before he’s finished? That question alone is intriguing.

I was fortunate enough to be at the beginning: at Old Trafford, Manchester, in August 1990, where the first Tendulkar Test century was posted. He’d already had us gasping in wonderment in the previous Test at Lord’s as he sprinted across the outfield and clung on to a one-handed catch from Allan Lamb. That was a Test remembered for Graham Gooch’s record 456 runs. The youngster would have watched the Englishman with more than casual interest. And a fortnight later, Tendulkar was the new name on everybody’s lips.

“Hail the boy king” was the headline I gave him in Wisden Cricket Monthly after the 17-year-old had saved the Old Trafford Test for India by batting for almost four hours for 119 not out. It was not a negative innings. He struck 17 fours, having already scored 68 in the first innings to keep India in the match. His patience was clearly obvious to the onlookers: he waited almost an hour for his first run of that first Test century. And afterwards he came into the press room to receive the Man of the Match award and a huge bottle of champagne. I can still recall his high-pitched response: “But I do not drink!”

All the clues to greatness were there: poise, calmness, crisp strokes when appropriate. But still, had somebody whispered that twenty years later this strongly-built little fellow would have a century of international centuries, that somebody would have been laughed away as a fantacist. Cricket’s statistical framework simply didn’t permit of such a phenomenon.

There are enthusiastic Indians who have seen almost every one of his runs home and away, thanks to the convenience of television. For someone who has seen him intermittently over the years, the effect is just as thrilling. Here he is again, defying the bowlers in Brisbane or Sydney, or Lord’s or The Oval, or on TV, driving West Indian or South African or Sri Lankan bowlers mad.

I was also fortunate enough to see his 241 and 60, both unbeaten, against Australia at Sydney in 2004, a wonderful double performance, which rather spoilt Steve Waugh’s final Test match.

India made a massive 705 for seven in the first innings, and the match ended as a draw, Tendulkar symbolically catching Waugh for 80 to seal off the Australian’s 168-Test career. Tendulkar himself was then thirty years of age, and people must have been wondering how much cricket was left in him. But on and on he has progressed, weathering brief and inevitable losses of peak form, just as Bradman once did.

So what did the greatest of a former era think of the greatest of our time? Sir Donald, who famously averaged 99.94 in his 52 Test matches spread over twenty years, interrupted by the Second World War, wrote in a 1998 letter to me (when he was 89, three years before he died) that when he was watching Sachin Tendulkar’s ‘magnificent’ batting, he felt himself in tune with his technique and his aggression. “So many batsmen wait on the defensive for a bad ball. My philosophy was to try and score off every ball and to take the initiative and I feel Tendulkar does this.”

There have been times when both Bradman in his day and Tendulkar in recent years have had to ‘shut shop’ for a while, weathering difficult conditions and bowling against which it would have been unnecessarily risky to play with freedom. But this was always only as a last resort.

It is tempting to mark down Bradman and Tendulkar as the finest two batsmen who ever lived. Players such as WG Grace, Jack Hobbs, Wally Hammond, Graeme Pollock, Garry Sobers, Viv Richards and several others have been marked very highly indeed. The ‘argument’ can never be settled absolutely. That’s cricket for you. It’s not as simple as timing the world’s fastest runner or swimmer. How many runs would the old-time batsmen have made had they played so many Test matches? How many would the moderns have scored if they had to bat on some of the treacherous wet pitches pre-1970?

Suffice it to say that there would probably be no other pair of cricketers (Sir Donald & Sachin) who could stand together to be photographed and for that photo then to sell for $A22,000 at a black-tie dinner in Adelaide in 1998. From that meeting sprang another precious Bradman quote regarding India’s batting star of stars: “He is a lovely and impressive character.”

Tendulkar is indeed a credit to the precious game of cricket, and that is every bit as important as we celebrate his amazing run-making record.

![submenu-img]() MBOSE 12th Result 2024: HSSLC Meghalaya Board 12th result declared, direct link here

MBOSE 12th Result 2024: HSSLC Meghalaya Board 12th result declared, direct link here![submenu-img]() Apple iPhone 14 at ‘lowest price ever’ in Flipkart sale, available at just Rs 10499 after Rs 48500 discount

Apple iPhone 14 at ‘lowest price ever’ in Flipkart sale, available at just Rs 10499 after Rs 48500 discount![submenu-img]() Meet man who left high-paying job, built Rs 2000 crore business, moved to village due to…

Meet man who left high-paying job, built Rs 2000 crore business, moved to village due to…![submenu-img]() Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...

Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...![submenu-img]() Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'

Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

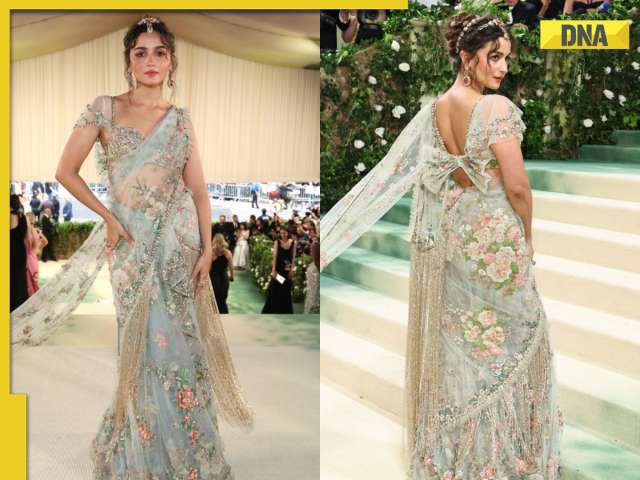

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...

Meet star, who grew up poor, identity was kept hidden from public, thought about suicide; later became richest...![submenu-img]() Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'

Watch: Ranbir Kapoor recalls 'disturbing' memory from his childhood in throwback viral video, says 'I was four years...'![submenu-img]() This superstar was in love with Muslim actress, was about to marry her, relationship ruined after death threats from..

This superstar was in love with Muslim actress, was about to marry her, relationship ruined after death threats from..![submenu-img]() Meet Madhuri Dixit’s lookalike, who worked with Akshay Kumar, Govinda, quit films at peak of career, is married to…

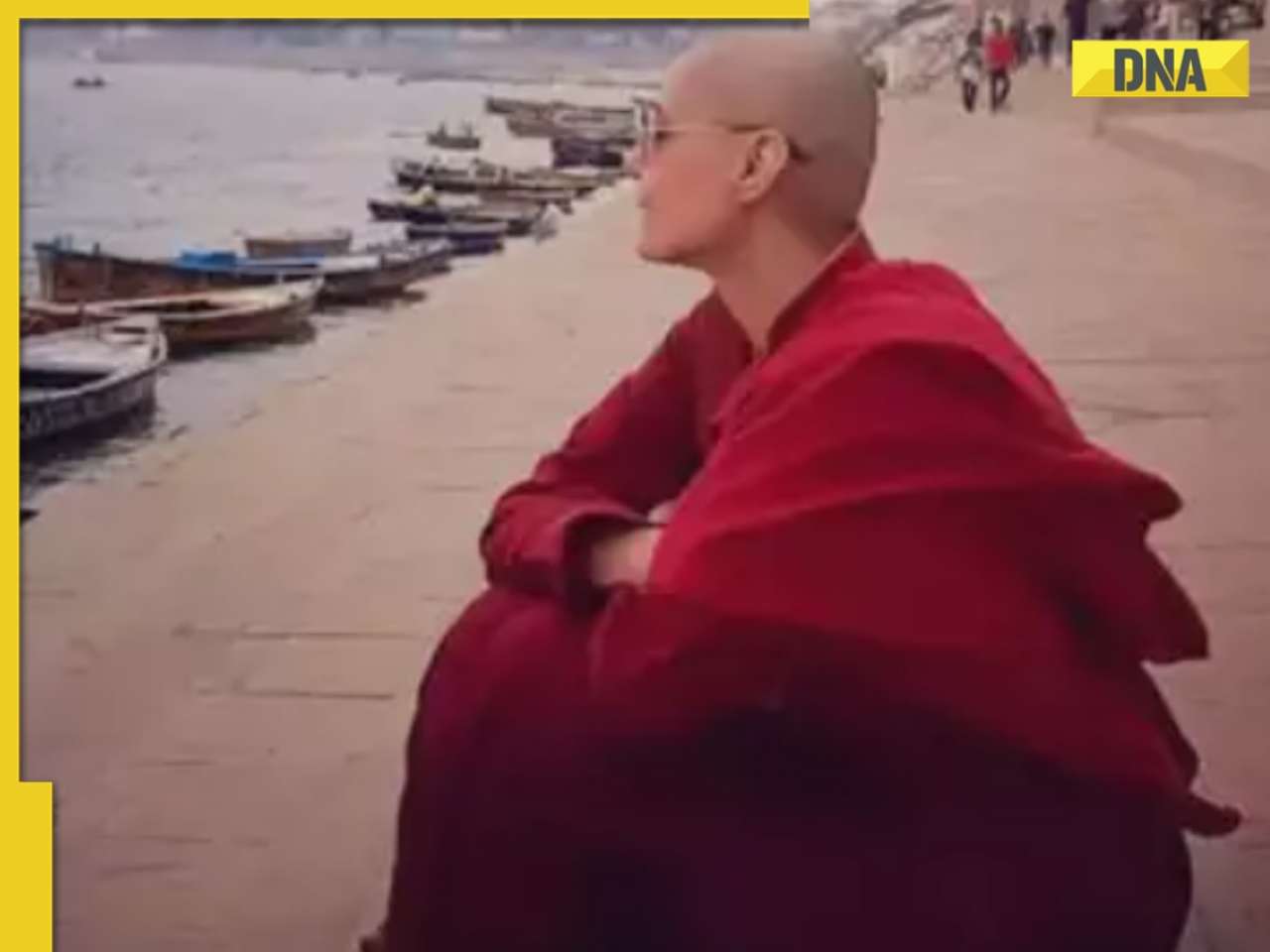

Meet Madhuri Dixit’s lookalike, who worked with Akshay Kumar, Govinda, quit films at peak of career, is married to… ![submenu-img]() Meet former beauty queen who competed with Aishwarya, made debut with a superstar, quit acting to become monk, is now..

Meet former beauty queen who competed with Aishwarya, made debut with a superstar, quit acting to become monk, is now..![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Abishek Porel power DC to 20-run win over RR

IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Abishek Porel power DC to 20-run win over RR![submenu-img]() SRH vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Here’s why CSK star MS Dhoni batted at No.9 against PBKS

IPL 2024: Here’s why CSK star MS Dhoni batted at No.9 against PBKS![submenu-img]() SRH vs LSG IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Lucknow Super Giants

SRH vs LSG IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() Watch: Kuldeep Yadav, Yuzvendra Chahal team up for hilarious RR meme, video goes viral

Watch: Kuldeep Yadav, Yuzvendra Chahal team up for hilarious RR meme, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Not Alia Bhatt or Isha Ambani but this Indian CEO made heads turn at Met Gala 2024, she is from...

Not Alia Bhatt or Isha Ambani but this Indian CEO made heads turn at Met Gala 2024, she is from...![submenu-img]() Man makes Lord Hanuman co-litigant in plea, Delhi High Court asks him to pay Rs 100000…

Man makes Lord Hanuman co-litigant in plea, Delhi High Court asks him to pay Rs 100000…![submenu-img]() Four big dangerous asteroids coming toward Earth, but the good news is…

Four big dangerous asteroids coming toward Earth, but the good news is…![submenu-img]() Isha Ambani's Met Gala 2024 saree gown was created in over 10,000 hours, see pics

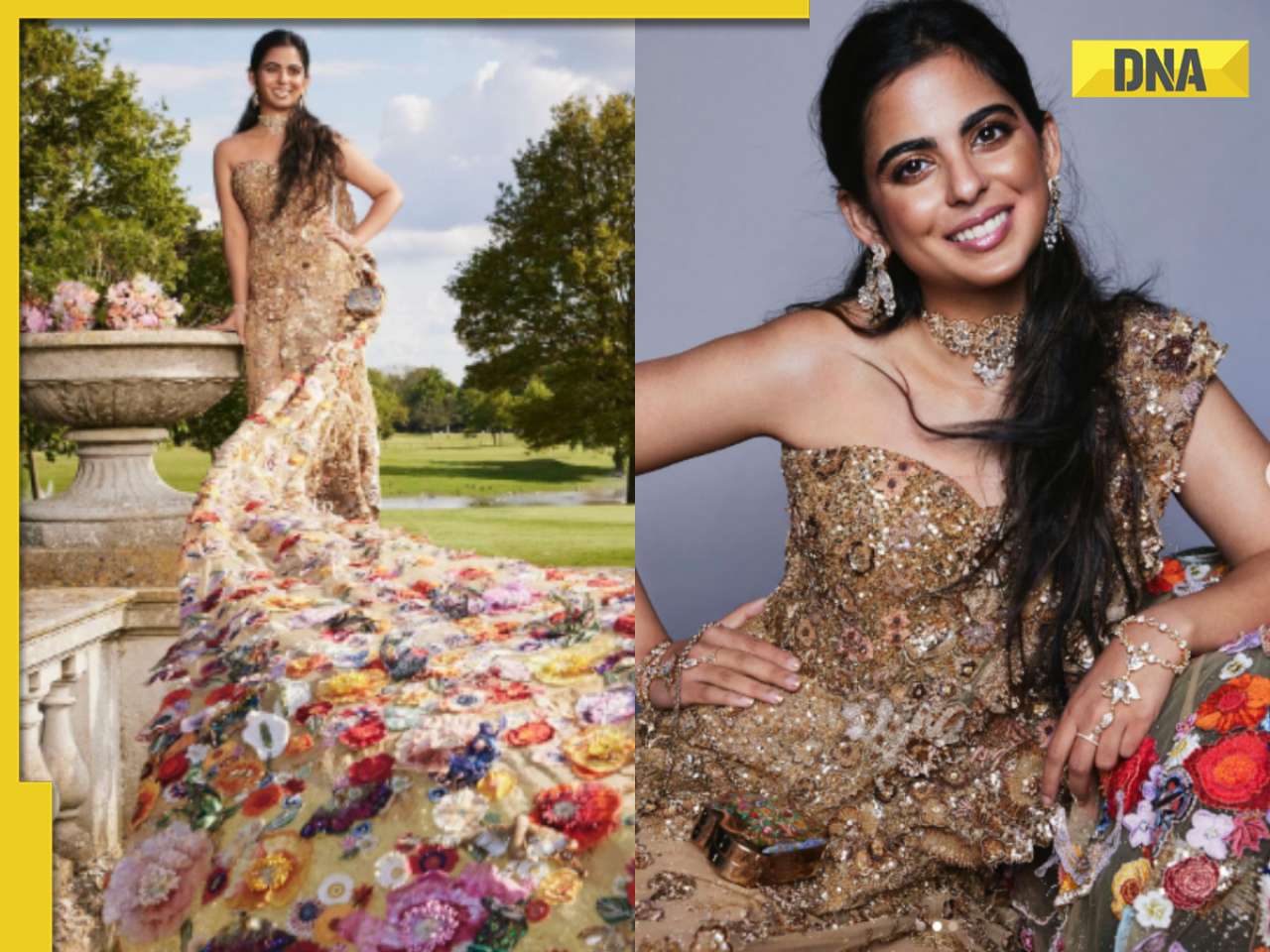

Isha Ambani's Met Gala 2024 saree gown was created in over 10,000 hours, see pics![submenu-img]() Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...

Indian-origin man says Apple CEO Tim Cook pushed him...

)

)

)

)

)

)