At first meeting, Volodin gives the impression of being a straightforward man from the provinces with simple tastes and manners.

Few people would recognise Vyacheslav Volodin on the streets of Moscow but the man who is the brains behind Vladimir Putin's presidential election campaign would have it no other way.

The square-faced, 48-year-old bureaucrat has quietly risen through the ranks to become the grey cardinal plotting the prime minister's return to the presidency in an election on March 4.

Brought into the Kremlin on December 27 in response to the biggest opposition protests of Putin's 12-year rule, he is behind a campaign that portrays the former KGB spy as a man of the people and a guarantor of stability.

At first meeting, Volodin gives the impression of being a straightforward man from the provinces with simple tastes and manners. He likes to crack jokes with reporters and sometimes has a mischievous glint in his eye.

But colleagues say the casual camaraderie hides a driving ambition and ruthless streak that has helped him see off rivals on his way to the top. Those who work or have worked with him seemed scared of saying too much for fear of retribution.

"I cannot say what I would like to say about him. What I can say is of no use to you," said a senior official in United Russia with good knowledge of Volodin.

Volodin did not respond to a request for an interview and most colleagues or former colleagues who agreed to discuss his career did so on the condition they were not identified.

In the shadows Volodin has worked his way up from a political aide in the Saratov region in southern Russia in the 1990s, through the ranks of Putin's United Russia party to roles in the government and now the Kremlin.

He has mostly kept in the shadows, especially since he became first deputy chief of staff in the presidential administration in a reshuffle following the start of mass protests over alleged fraud in a December 4 parliamentary election.

Volodin's challenge is to ensure Putin wins 50% of the votes on March 4 to avoid a second-round runoff, which could undermine his authority. Some political experts say he is a good choice because he is the only person in Putin's inner circle with deep experience of the election battles of the 1990s, when competition was fierce and campaigning was dominated by mudslinging and muck-raking.

"Volodin went through the rough school of alternative elections in the 1990s. This experience has enabled him to push Putin's campaign in a more aggressive direction," wrote Alexei Venediktov, editor-in-chief of Ekho Moskvy, a liberal radio station.

Others say Volodin - whose personal fortune was estimated at $95 million by a Russian magazine after he made money on shares in margarine factories - may not have what it takes. "Volodin is a clever executor, but he cannot come up with a political project of his own. It is not his strength. He can only manage somebody else's project," said Gleb Pavlovsky, a former Kremlin adviser who fell out of favour last year.

Eminence grise

What is not in doubt is that Volodin has assumed the mantle of "eminence grise" as first deputy chief of staff in the Kremlin since replacing Vladislav Surkov, the architect of the closely managed political system forged in Putin's presidency.

Volodin has relied little so far on modern tools such as videoclips and the Internet in a campaign which mostly features Putin holding televised meetings with core supporters such as factory workers, football fans and sportsmen.

Putin, seeking a six-year term as president, has also set out his policy plans in a series of newspaper articles and focused his travel on provincial towns where support for him is stronger than in the big cities.

"Volodin exerts a big influence on Putin. These articles and meetings with ordinary people look like his typical tricks. It's as clear as day. The rest of Putin's election campaign will be the same," said a political source who has worked with Volodin.

Putin, 59, has gradually softened his tone towards the street protesters. Some opposition leaders have been granted a little more access to Russia's state-dominated media.

But opposition leaders also see Volodin's influence at work in the release of taped telephone conversations in which one protest leader, Boris Nemtsov, used derisory language to describe another, Yevgenia Chirikova.

He is also widely seen as behind the organisation of pro-Putin rallies intended to counter the opposition protests, which look increasingly likely to pose a sustained challenge to Putin. Sources in United Russia say Volodin won Putin's ear with an idea to create the All-Russian People's Front, an umbrella organisation designed to woo unaffiliated candidates to run on the party's ticket in last December's parliamentary election.

The Front has become a vehicle for Putin's campaign and the prime minister has distanced himself from United Russia since its parliamentary majority was reduced in the December vote. Volodin benefited by having access to Putin in his previous role as government chief of staff and first deputy premier. Surkov, alienated by not being consulted, was seen laughing, yawning and casting scornful looks as Volodin introduced new Front members to Putin, Kremlin insiders said. Volodin also impressed Putin by helping United Russia win 65 percent of the votes cast in Saratov, his home region, in the December election. In the end, Surkov is - at least for now - the loser in the rivalry with Volodin.

Workaholic

Volodin is sometimes mentioned in the same breath as Vyacheslav Molotov, one of late Soviet dictator Josef Stalin's foreign ministers.

Like Molotov, he is often called "Iron Arse" for spending long hours at his desk. Volodin and Molotov were both born in remote villages and each was seen as a provincial mediocrity before gradually rising through party ranks and sidelining more outspoken colleagues. Volodin was born in 1964 in the village of Alexeyevka on the Volga river and got his first job as a tractor mechanic at the age of 15.

He then moved to the regional centre Saratov where at the age of 26 he joined the city's administration.

The investigative newspaper Novaya Gazeta reported in 2006 that Volodin hunted rabbits as a child with his grandfather's double-barrelled gun and prefers now to hunt foxes and wolves.

But asked about his pastimes in a rare interview with a regional Russian newspaper, he said only that his favourite hobby was visiting rare villages where he could help people out. His first big electoral success was in helping his boss, deputy mayor Dmitry Ayatskov, win a seat in Russia's upper house of parliament in 1994.

One of Ayatskov's rivals, Yuri Kitov, committed suicide after the bitter campaign. Volodin soon climbed to the rank of a deputy to the regional governor, Ayatskov, but made enemies along the way.

"Volodin was very well known in Saratov as a person always engaged in intrigues," Pavlovsky said. Local businessman Leonid Feitlikher wrote in an open letter to Volodin:

"Why do you have conflicts with everyone in Saratov? The city has become a testing ground for your political experiments."

Feitlikher later faced a criminal investigation on fraud charges and emigrated to Israel. In 1999 Volodin joined the Otechestvo (Fatherland) party created to take on President Boris Yeltsin and his inner circle of family members and rich businessmen, and won a seat in the lower house of parliament where he headed its deputies group. Volodin went on to become a leader of United Russia, which was formed after Otechestvo merged with another party, Unity.

Presidential ambitions?

Some former colleagues say Volodin's personal ambition could eventually put him on a collision course with Putin.

"Volodin? I think he is the future president of Russia," said a source in the leadership of United Russia who used to work with Volodin. "He likes to fly high. In six years he will be a real candidate."

Another person who was close to Volodin when he worked in Saratov said that by 1992 he was telling his friends half jokingly that he would one day be president. Others say he lacks the qualities needed to be a public politician or leader.

"He is a careful, rather clever bureaucrat, capable of intrigue but he is not a politician and even less of a strategist," said one Kremlin insider.

In 2006, Russia's Finans magazine listed Volodin as the 351st richest Russian with a fortune of $95 million, mainly in the form of stakes in various margarine factories.

The publication triggered complaints from the opposition. Volodin said he bought the stakes in the 1990s when they cost $190,000. Volodin's spokesperson said he sold the stakes in 2009 for $7 million which was reflected in his declaration.

If Putin wins the March election as expected, Volodin is likely to retain his Kremlin job and will then face the task of handling the growing protest movement, demanding free and fair elections and calling increasingly for Putin to go.

He has not discussed his ambitions in public but success in his influential role could eventually lead to higher things.

"If Putin has no energy to run again in 2018, Volodin will be among those who could bid for his seat," said Saratov journalist Dmitry Kozenko who has reported on Volodin.

![submenu-img]() Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...

Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...![submenu-img]() 2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…

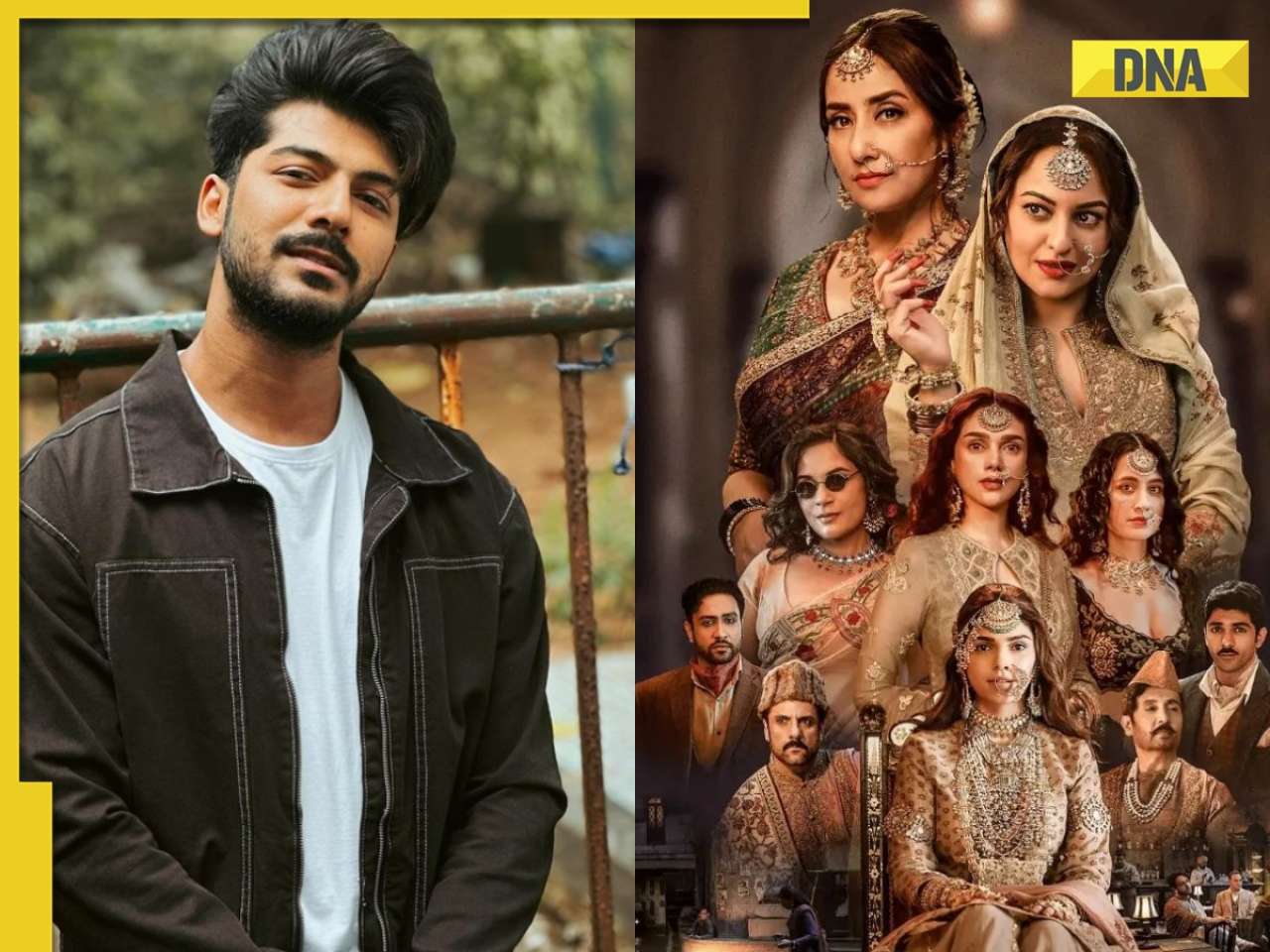

2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…

Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…![submenu-img]() Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police

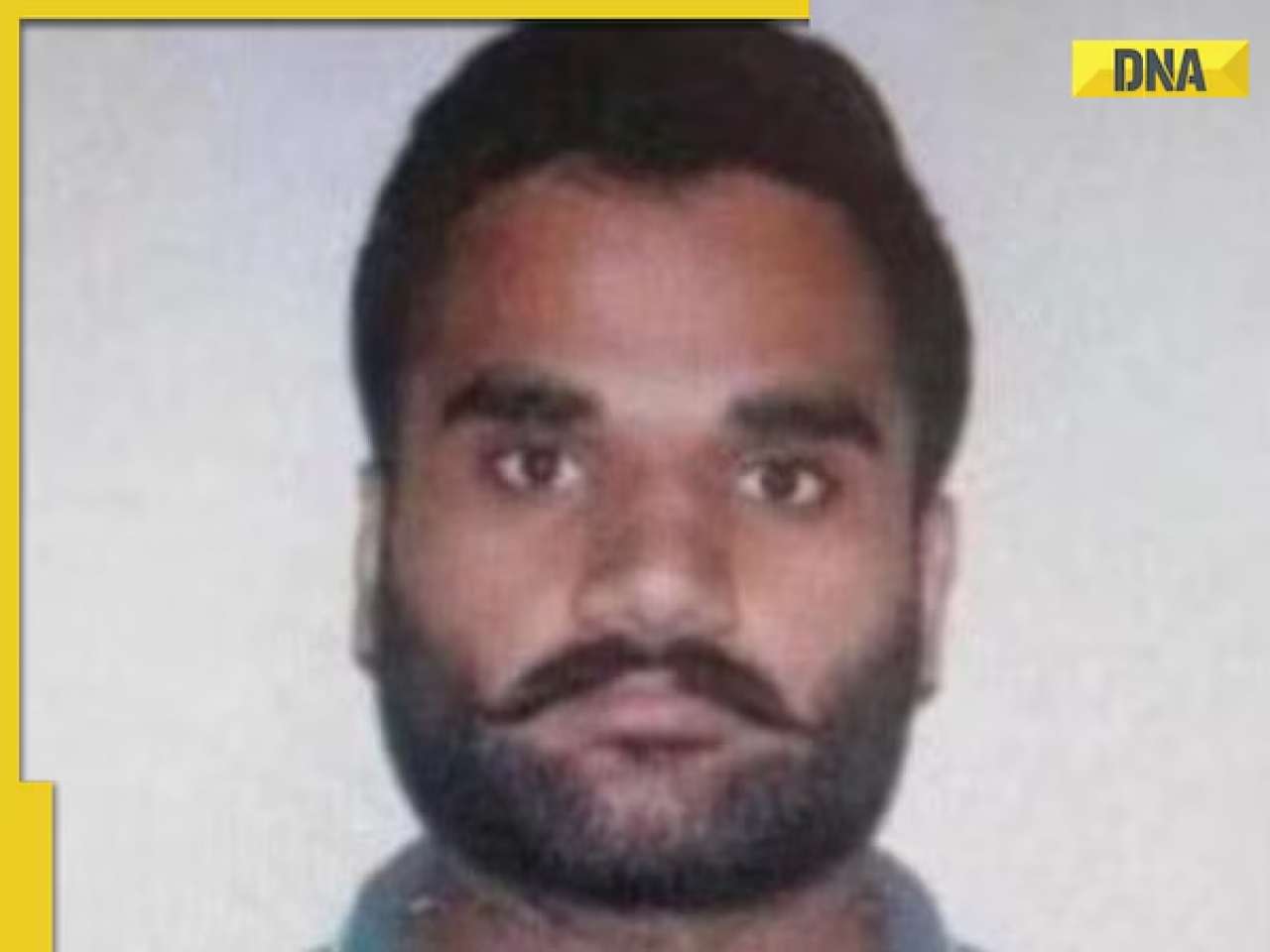

Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..

Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’

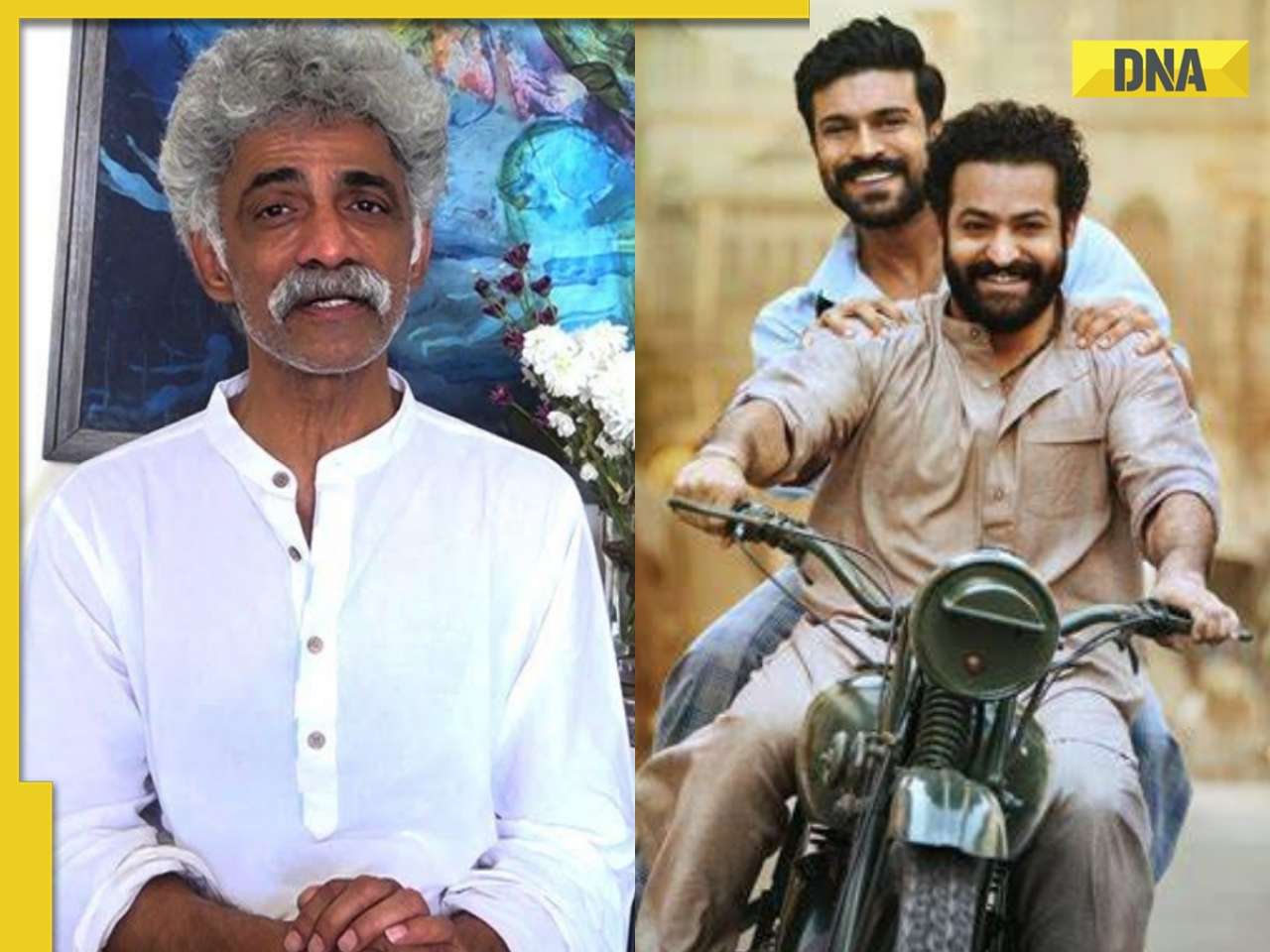

Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’![submenu-img]() Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...

Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...![submenu-img]() Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore

Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets

IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets![submenu-img]() Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here

Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals

SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch

Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch

Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts

Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet

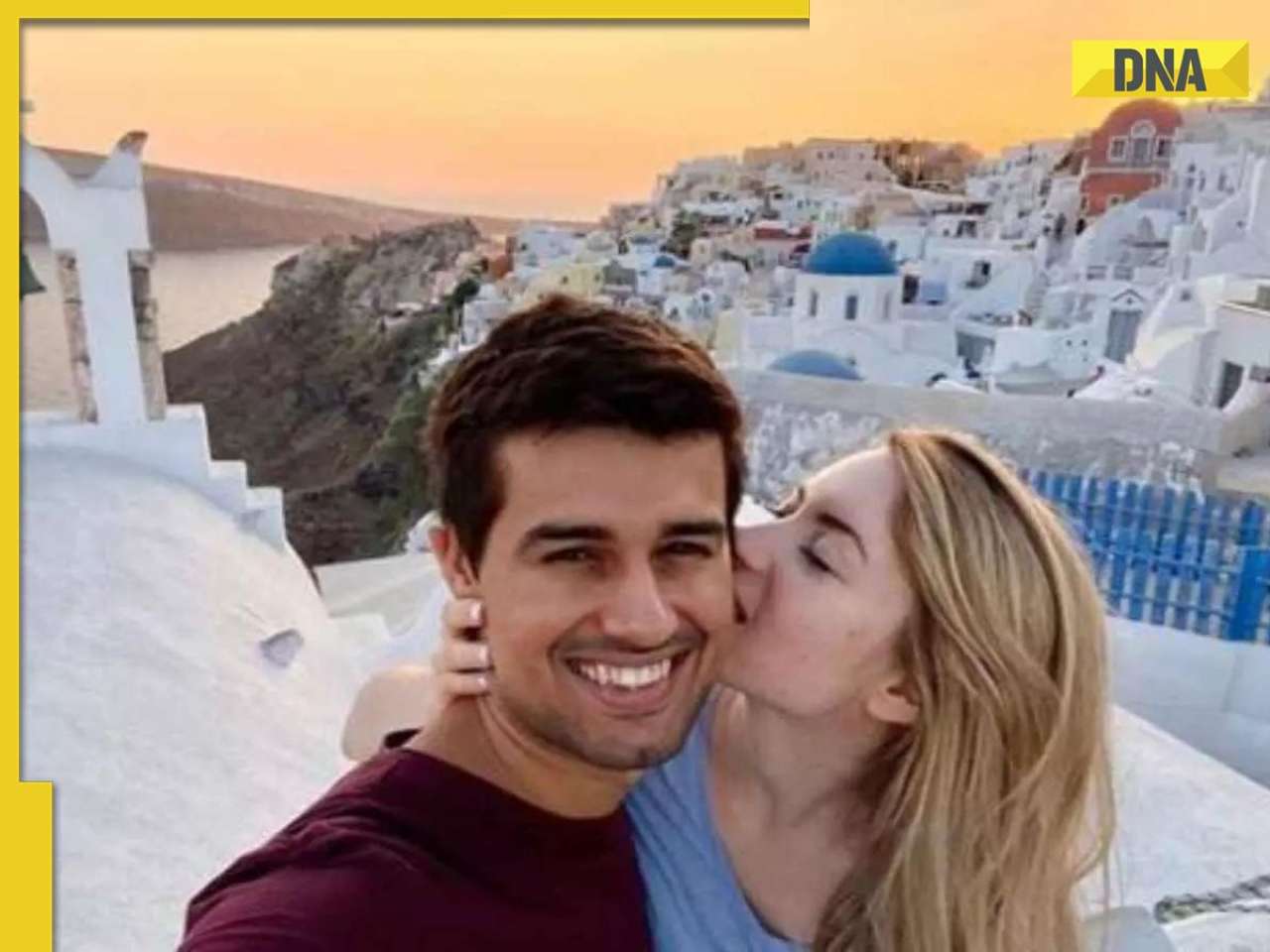

Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet![submenu-img]() Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)