Myanmar is expected to release 6,359 prisoners who are not a threat to the stability of state or public tranquility and have shown good conduct.

Reclusive Myanmar is expected to release a number of political detainees on Wednesday under an amnesty for thousands of prisoners announced after the national human rights commission urged the president to free "prisoners of conscience". The United States, Europe and Australia have made the release of an estimated 2,100 political prisoners a key condition before they would consider lifting sanctions imposed on the pariah Southeast Asian state.

State television said 6,359 prisoners who are "elderly, sick, disabled or have served their punishment with good conduct and character" would be freed on Wednesday, but did not say if political detainees would be among them.

General prisoner amnesties are fairly common in Myanmar. A May amnesty for 14,000 inmates included just 47 political prisoners, which human rights activists called a token gesture.

But there may be more reason for optimism this time. One lawmaker, who attended a meeting on Friday in the capital, Naypyitaw, told Reuters the release of political prisoners could come "in a few days". He said that was the message given by Shwe Mann, the Lower House speaker.

In an open letter published on Tuesday, Win Mra, chairman of the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission, wrote that prisoners who did not pose "a threat to the stability of state and public tranquility" should be released. "The Myanmar National Human Rights Commission humbly requests the president, as a reflection of his magnanimity, to grant amnesty to those prisoners and release them from the prison," the letter ended.

The commission was formed last month by President Thein Sein, a former general but who took over this year as the first civilian head of state in half a century. The open letter marks a significant shift in the former British colony, also known as Burma, where authorities have long refused to recognise the existence of political prisoners, usually dismissing such detainees as common criminals.

There have been other significant signs of change since the army nominally handed over power in March to civilians after elections in November, a process ridiculed at the time as a sham to cement authoritarian rule behind a democratic facade. Recent overtures by the government have included calls for peace with ethnic minority guerrilla groups, some tolerance of criticism and more communication with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, who was released last year from 15 years of house arrest.

"It raises the question of whether the government is indeed moving towards some serious relaxation of its control of the population and of the way politics works in Myanmar," said Milton Osbourne, Southeast Asia analyst at Australia's Lowy Institute for International Policy.

Last week, the government suspended a controversial $3.6 billion, Chinese-led dam project, a victory for supporters of Suu Kyi and a sign the country was willing to yield to popular resentment over China''s growing influence. These moves have stoked hopes the new parliament will slowly prise open the country of 50 million people that just over 50 years ago was one of Southeast Asia's wealthiest as the world's biggest rice exporter and a major energy producer.

STRATEGIC

Nestled strategically between economic powerhouses India and China, Myanmar has been one of the world's most difficult for investors, restricted by sanctions, blighted by 49 years of oppressive military rule and starved of capital despite rich natural resources, from gemstones to timber to oil.

In November 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama offered Myanmar the prospect of better ties with Washington if it pursued democratic reform and freed political prisoners, including opposition leader Suu Kyi. But Washington's demands go beyond prisoners, making it unclear whether it would lift sanctions if the prisoners are released and Suu Kyi withdraws her support for sanctions.

The United States has also demanded more transparency in Myanmar's relationship with North Korea and an end to human-rights abuses involving ethnic minorities in remote regions bordering Thailand and China.

A European diplomat in Bangkok said many European countries had privately urged the European Union to ease sanctions and that the EU could face strong internal pressure to do so if prisoners were released and Suu Kyi changed her stance. "All it would take is for Suu Kyi to urge sanctions to come down," said the diplomat, who declined to be identified because of the sensitivity of the subject.

In Tokyo, a foreign ministry official said Japan had resumed some aid to Myanmar in June after the release of Suu Kyi and other signs of reform. "We may continue with this stance if there are more releases of political prisoners," the official said. "Work still needs to be done in terms of democracy but we think they are moving in the right direction."

Myanmar also appears to be trying to convince the 10-member Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) to allow it to take its rotating presidency in 2014, two years ahead of schedule and a year before the next general election. Hosting ASEAN would give Myanmar a degree of international recognition and help convince the World Bank and other multilateral institutions to return to the impoverished nation.

It is unclear whether all political prisoners would be released at once, or indeed how many would be freed. Nyan Win, a spokesman for Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy, said he had not heard whether political detainees would be freed. Families of prisoners also had not been told. "We are still trying to find out," said Ma Nyein, sister-in-law of Zar Ga Nar, a jailed comedian and government critic.

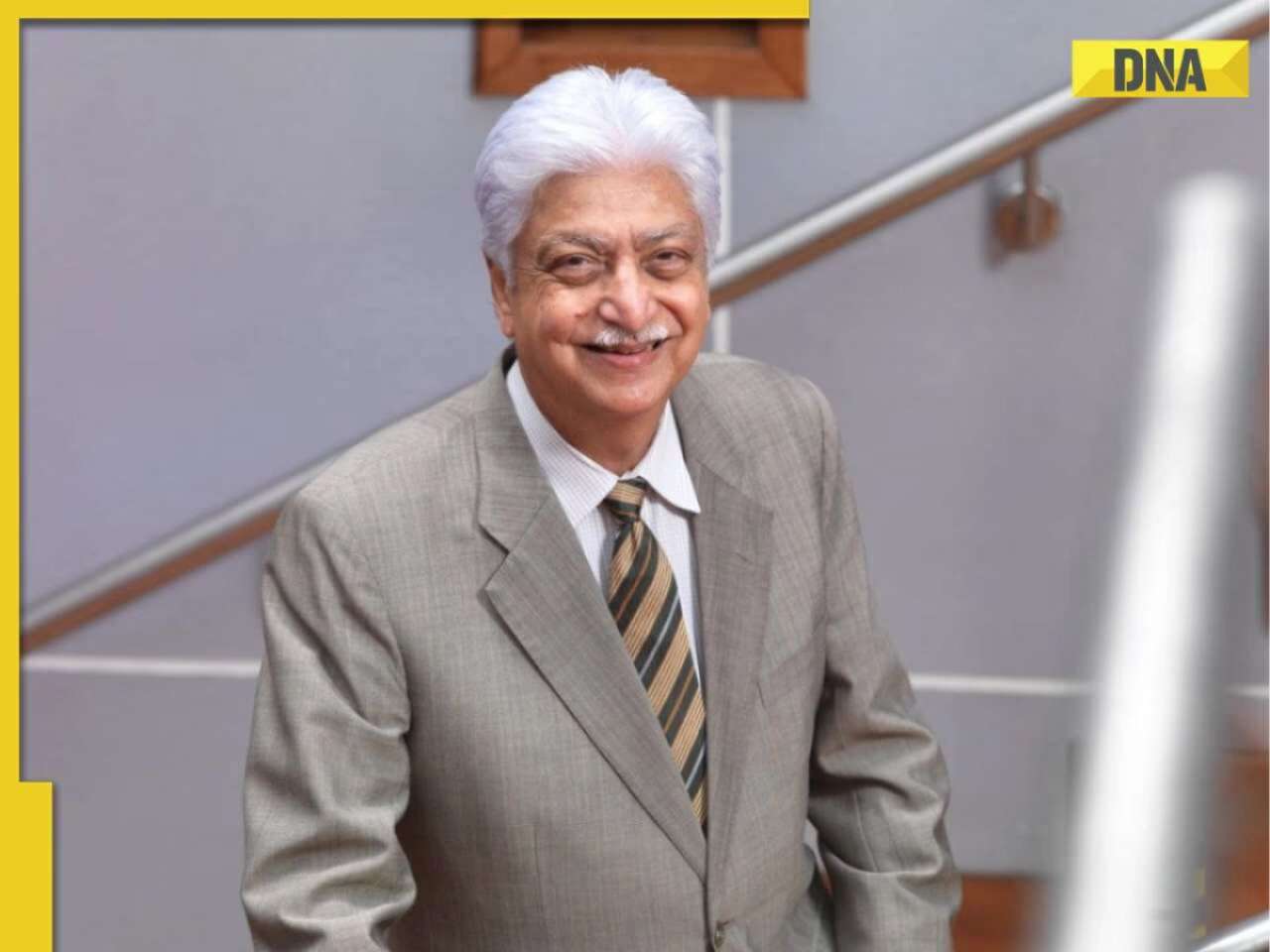

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

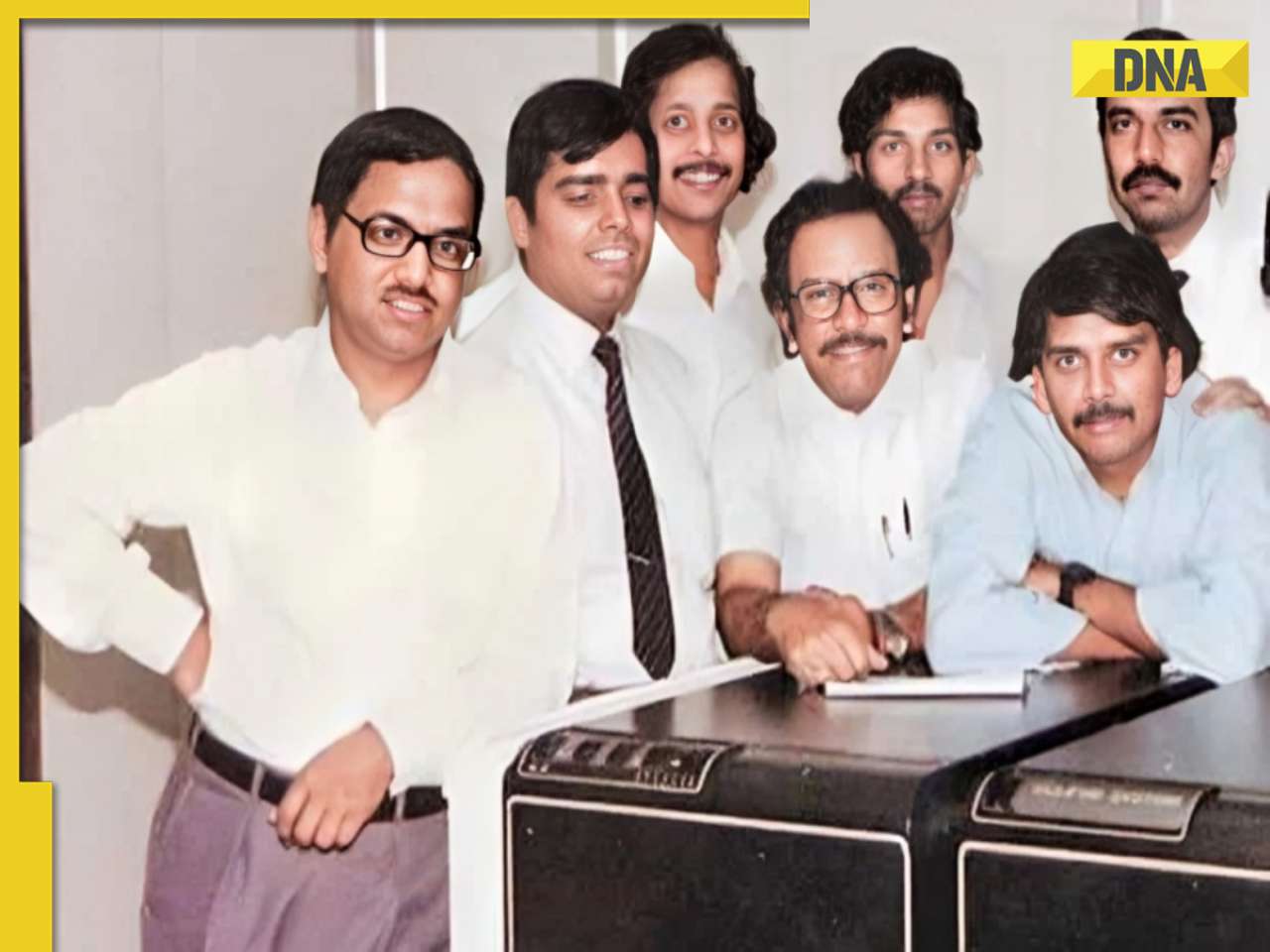

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)