A Russian GM once declared that Anand will never become a world champion but the Indian maestro proved him, his country and the world wrong by winning the crown not once but four times.

This is back in 1983, at the National Chess Team championships in Mumbai. A small crowd had gathered around a table where a 14-year-old boy was playing, after his opponent had called the arbiter to complain that the boy’s clock wasn’t working.

The clock was; just that Viswanathan Anand had consumed one minute to complete as many moves as his opponent had in an hour.

This, Grandmaster Pravin Thipsay says, was the first time he had heard of the boy. “I was playing in the adjoining hall and my brother told me about this incident at the end of the day. The next day, out of curiosity, I went to watch him in action. I remember he was ill, covered in a blanket, looking in a lot of discomfort and still he was making his moves in split seconds,” Thipsay told DNA.

He knew then that the boy was special. He didn’t know he would spark a revolution across 64 squares. If one man’s impact on a sport across a country could be quantified, there would be few parallels. This, seemingly without trying. How did that sweet, bespectacled boy of 14 whose “clock didn’t work” make it this far?

The journey started, says his mother, about 35 years ago when Anand, then six, started picking up the game that was played regularly at home.

“Slowly he started going to small, weekend tournaments, soon he started winning them. Then he started taking part in district level tournaments and started winning them. There was this one time when he won the sub-junior, junior and senior categories in the same national level tournament…” she says.

It was when the family moved to the Philippines, after his father was posted there for a couple of years, that Anand saw how crazy people could be about chess. “People there used to play chess everywhere… on the bus, in the parks. Every afternoon, there used to be a chess show on television, where Grand Masters used to analyse important matches and then set a small quiz: black to win in three moves and so on. The winner used to get a chess book from a library. I remember him winning a lot of books.”

He won so many books, Anand once admitted, that the people from the show had asked him to come around and take as many

as he wanted.

It was only in 1985, Thipsay says, that the world took notice of the prodigy who was now 15. “We were in London for a tournament, and Anand beat a GM, Jonathan Mestel, with just 10 minutes on the clock. What a few of us had seen in 1983, the world was seeing now. His natural judgement and grasp of positions was shocking.”

During that tournament, the BBC ran a story on Anand, titled the ‘Lightening Kid’. “That story made a big impact. Back home, chess was covered sporadically in the print media, but after that, Doordarshan started showing chess programmes.”

The world of chess, at the time, was split in their reaction to this phenomenon, Thipsay says. “The western world wanted the USSR domination to end, so they looked at Anand as a big hope. There were a few players in the USSR, however, who did not rate him highly at all. I remember one Russian GM, after losing to Anand said that he would never become world champion. But most people treated this boy from India with respect, even when he wasn’t a GM.”

By the time he was 16, he had won two national titles and in 1988, got GM status. His first world championship match came against Garry Kasparov in 1995, and it was one that was followed with high expectations in India. After drawing the first eight games, Anand took the lead at the WTC clash in New York, but lost three of the next four rounds to suffer a heavy defeat. By the time he won the title, beating Alexei Shirov in the final after a gruelling knock-out in 2000, the sport itself was gaining mainstream status in India.

All India Chess Federation secretary DV Sundar has no hesitation in terming Anand an icon. “I always call Anand a one-man army,” Sundar says. “Not only his chess, but his overall behaviour and character are impeccable. He has inspired many youngsters to play the game. Parents too feel that their children have a future in the game.”

“Whenever he came to India, he would invite batches of 10 players for dinner,” says GM RB Ramesh, who runs Chess Gurukul in Chennai. “We would discuss chess at length and seek clarifications from him. He keeps a tab of all of us and regularly sends congratulatory messages or SMSes. It’s highly motivating.”

His win against Topalov took his count to four, the number of Indian GMs is up to 21 (plus 65 IMs), and it’s practically impossible to put a figure on how many kids are playing the game, even if recreationally.

Thipsay, however, feels there’s scope to capitalise on Anand’s genius. “Kasparov was once asked how he got so good and he said that when 4.5m people in a country were playing competitive chess, a few world champions were bound to come around. Anand’s success has increased awareness and enthusiasm, now we need a structure in place that can produce another one.”

True as that might be, can there really be another like Anand?

(With inputs from D Ram Raj in Chennai)

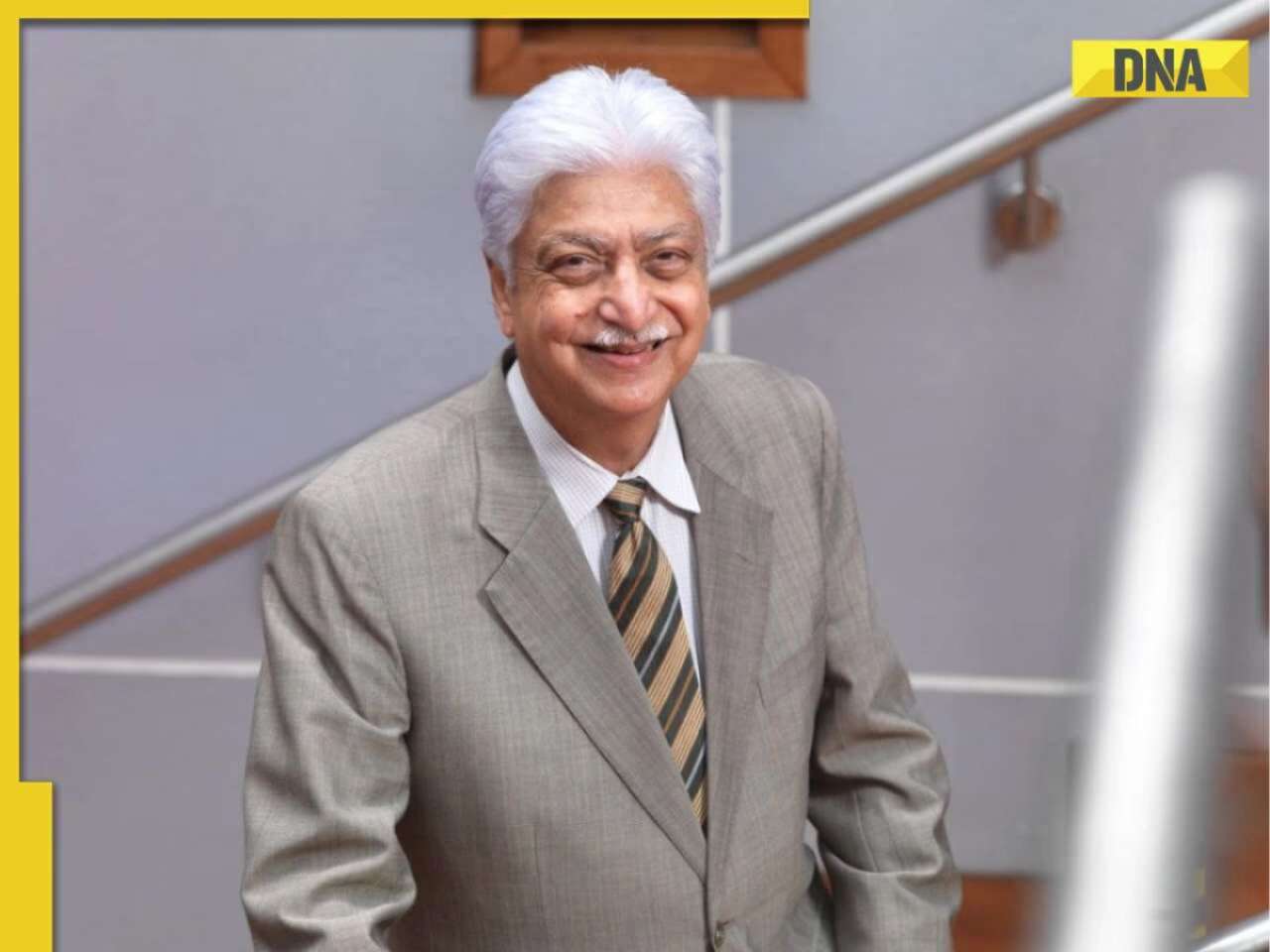

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)