If you tuned in to the Nagpur Test any time during Hashim Amla’s marathon unbeaten 253, you probably found him camped on the back foot. This is not the first time such a tactic has been used successfully to thwart our spinners and negate our home advantage in recent years. Damien Martyn along with tailender Jason Gillespie did exactly the same thing to bat through most of the fourth day on a Chennai track in 2004 to save the Test for the Australians and go on to win the series.

Time was when playing back to a good length ball would get a batsman into strife, and you had to be nimble on your feet to get to the pitch of the delivery and smother the spin. That’s why you had that cordon of close-in fielders to snap up bat-pad catches as the batsman lunged forward - a regular mode of dismissal for Ricky Ponting in the 2000 series, for example.

But if the pitch is too slow and low, as it was in Nagpur, batsmen have enough time to hang back and adjust to whatever deviation there is from a spinner. And if the ball is too full, they can just lean forward and tap it or whack it on the half-volley.

It’s not just Nagpur either. Even the traditionally spin-friendly venues such as Kolkata and Chennai have changed their character after the pitches there were re-laid. Earlier, they would decidedly get tricky by days 4 and 5, but now the soil composition is such, and they are so well rolled out, that in fact batting can become easier as the match progresses, as Martyn and Gillespie demonstrated.

It’s rumoured that the Kolkata pitch curator is under pressure to produce a dry, rank turner, just like we did in Kanpur after the South Africans had gone one up when they were here the last time, in which case Bhajji & Co. may get lucky. But in general the pitches in Mohali or Ahmedabad, Chennai or Kolkata, have been getting flatter and deader with each passing day, which is why Kamran Akmal managed to bat out almost the entire fifth day at Mohali and save a Test for Pakistan.

The art of flight

MAK Pataudi, who was the first to conceptualise a spin-based attack in home conditions to prey on the opposition’s weakness, agrees that these days “it’s often better to bring in the spinners quickly”, while there’s still some juice in the wicket.

But, more than in the pitches, he sees changes in our bowling and the visitors’ approach to spin. Take the bowling action, to begin with, which is fundamental to bringing the full repertoire of spin into play. When is the last time you saw a batsman being drawn forward and consumed in flight, for instance? “Harbhajan Singh has been a good bowler for India, but with an open-chested action it’s a little more difficult to beat the batsman in the air,” points out Pataudi. What that means is Bhajji has to mostly rely on the ball that turns and bounces to create a gloved or bat-pad chance, or the doosra, which he seems to have become a little more circumspect with after his action came under ICC scrutiny.

The limitations of this approach are perhaps becoming more apparent now, because playing spin in Indian conditions is no longer an alien experience for touring batsmen. “These guys used to come here once in a few years in our time. But now they visit frequently [for Tests, one-dayers, as well as the IPL],” observes Pataudi.

It may be one reason why, although centurion Jacques Kallis eventually perished lunging forward to offer a bat-pad chance off Harbhajan in Nagpur, that’s not a mode of dismissal you see too often these days. In fact, players from Australia and South Africa, especially, have taken a leaf out of the Indian batsmen’s book by improving their back foot play, and minimising the half-cock prod forward.

Spun like a top

Erapalli Prasanna, arguably the greatest off-spinner of all time, puts the onus squarely on the bowler, however, to make things happen against different batsmen in varying conditions. “If there is no life in the wicket, the bowler has to put life into it. Just up and down stuff will not threaten any batsman.”

Bishen Singh Bedi, a past master of guile in spin bowling, amplifies Prasanna’s observation by citing the example of Prasanna himself. “When I would stand near him at the stumps during practice, I could hear the whizz as the ball came off his palm, spinning like a top. It’s simple cricket logic: the more revolutions you impart on the ball, the more purchase you get off the wicket.”

One can only speculate about why Harbhajan Singh, Amit Mishra and Pragyan Ojha appear to lack the sort of zing that Bedi is talking about. In 2003, Harbhajan was to go to Australia for surgery on a ligament in the wrist, but decided against it. Who knows if he’s able to grip the ball as strongly as he used to? Or did the ICC scrutiny of his elbow action cramp his style? The fact is he mostly bowls a negative run-saving leg-stump line these days, which Bedi vehemently rejects.

“The dot ball has become the holy grail,” says Bedi, adding that he had overheard captain MS Dhoni on the stump mike instructing a spinner on a turning track: ‘kharid mat’ (don’t buy the batsman’s wicket). “Why should you not buy the batsman’s wicket?” asks Bedi. “Isn’t it better to have figures of 6 for 160 than 2 for 120?”

Whether you agree or not that the Indian spinners on view look jaded and bereft of ideas, what’s disheartening is that the likes of Bedi and Prasanna are not being tapped to identify and groom new spin talent in the country. For whatever reason.

![submenu-img]() Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...

Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...![submenu-img]() 2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…

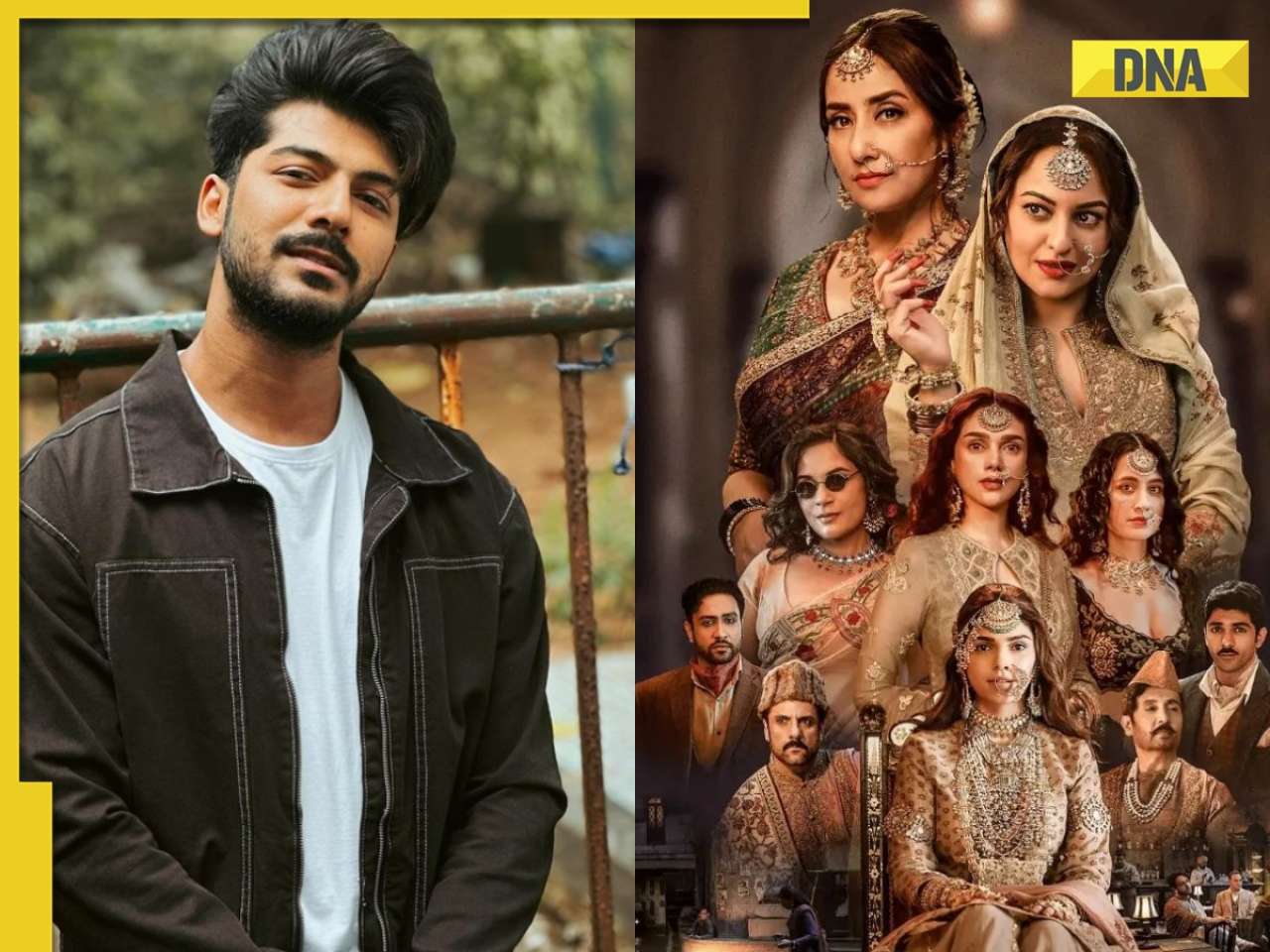

2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…

Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…![submenu-img]() Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police

Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..

Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’

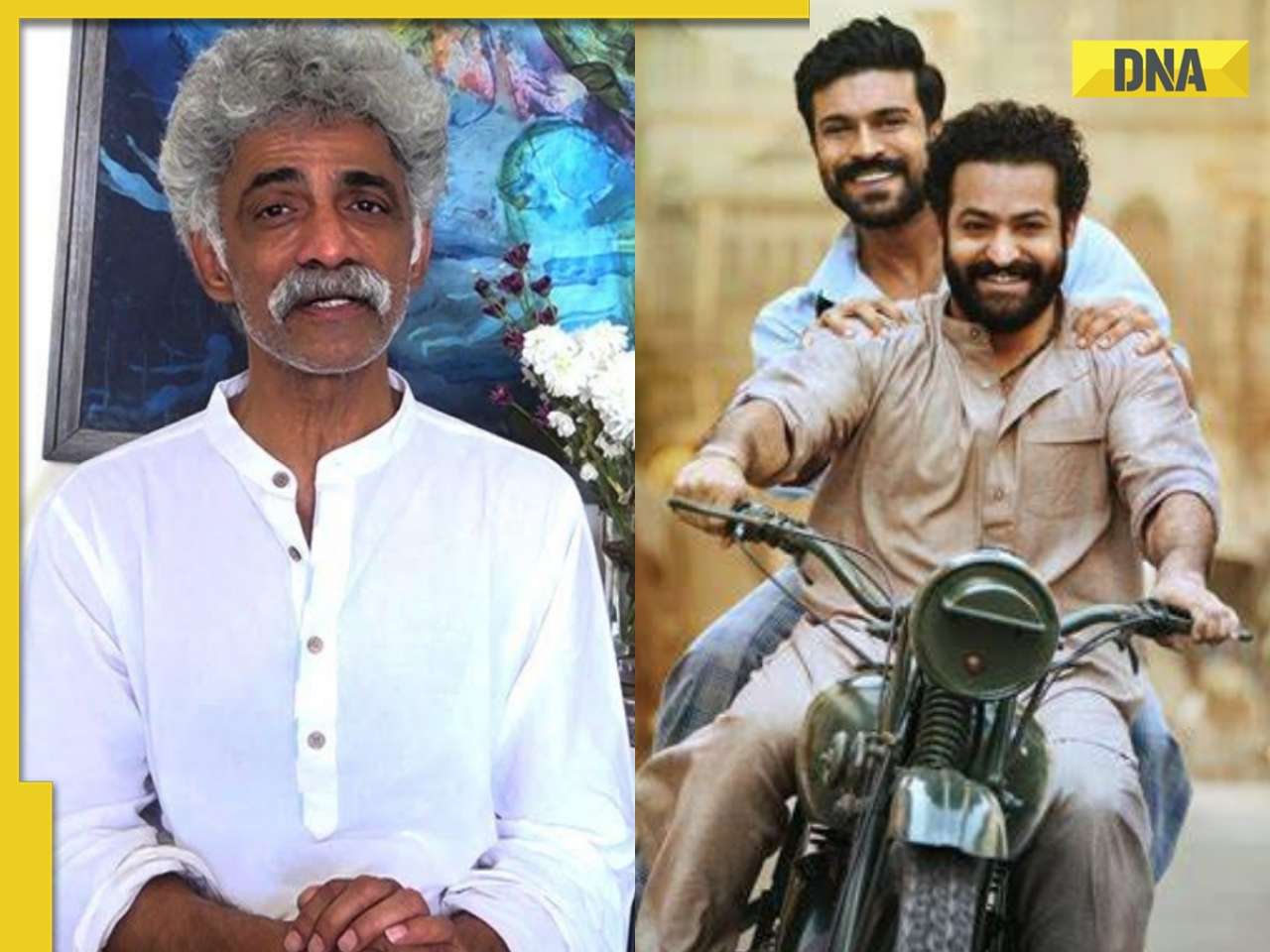

Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’![submenu-img]() Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...

Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...![submenu-img]() Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore

Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets

IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets![submenu-img]() Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here

Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals

SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch

Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch

Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts

Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet

Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet![submenu-img]() Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)