Extreme measures are thus often used, none more than biting away at the ball by the captain of an international side.

The phenomena of reverse-swing has made ‘ball doctoring’ an oft-seen act in modern cricket. The pace bowler’s sleight of hand and the aero-dynamical oddity that moves the ball the other way in the air, is usually the difference between victory and defeat.

Extreme measures are thus often used, none more than biting away at the ball by the captain of an international side.

‘Boom-boom Afridi’ might well be known as ‘Shahid chomp-chomp’ after he was caught on camera trying to add bite to his seam attack.

But his indiscreet act in the presence of cameras galore is not the first instance of working on the versatile cherry, the temptation of hapless players from the sub-continent having been more in comparison to others.

The first lesson you learn as a swing bowler is to take care of the new ball. “Keep one side shining,” you are reminded by teammates and you point the seam to where you aim to swing it, the rough side in the direction of the intended lateral movement.

But with reverse-swing, the dynamics of movement have changed both figuratively and literally. Nowadays, seam bowlers often wait for the ball to become old, so that they can impart the kind of movement which comes off faster and is more difficult to detect. In ‘reverse’, the ball moves towards the shinier side as it is made rough and heavy on the other one.

While swing bowling has been seen with respect over the years, reverse-swing has only gained acceptance recently. It has been practised with elan by different bowlers over the past two decades, and it is not surprising to see that most cases of ball tampering have been recorded in this era.

The domination of pace bowlers in the 1970s and early 80s and the subsequent slowing down of pitches has probably led to desperate measures from the practitioners of swing bowling.

“A swing bowler has to take care of the ball. Shining one side of the ball has been accepted down the years. It is only recently that tampering of the ball has come so much into focus,” says Manoj Prabhakar, an acclaimed exponent of swing bowling, whose pictures from a tour of New Zealand in which he was caught biting the ball a la Afridi, brought him back into focus recently.

Bowlers like Sarfaraz Nawaz, Sikandar Bakht and Imran Khan, who grew up bowling traditional swing, were to learn that the ball could do a little bit even later in the match. Thus started a Pakistani tradition that was frowned upon by many, most notably the Englishmen.

Life came a full circle when England’s bowlers led by

Andrew Flintoff used the same art to conquer the Aussies in an epic Ashes clash in 2005.

Sarfaraz once sued England’s Allan Lamb over claims that the Pakistani bowler had shown him methods to lift the seam while they were teammates at Northamptonshire, while Imran was in litigation with Lamb and Ian Botham after his famous words on the same subject that indicated a bias on the basis of skin colour.

“There is a lot of racism here. How come the noise started when the West Indies and Pakistan began winning matches with their fast bowlers? Australians can get away with anything because they are white...Look at people such as Lamb and Botham making statements like: ‘Oh, I never thought much of him anyway and now it’s been proven he is a cheat.’ Where is this hatred coming from?” he was quoted as saying then.

Botham once recalled the state of the ball after a one-dayer in 1992, when Akram and Waqar were tormenting batsmen the world over: “On one side it was so badly chewed up that it looked about 300 overs old. The other side was perfectly normal. Over the years, I have seen Pakistan players fiddle with the ball illegally and they were at it again.”

There is credence to the Pakistani viewpoint: “When we did it, we were conmen. When England did it against Australia in 2005, they were called heroes.”

Necessity is the mother of all inventions and seamers on the sub-continent needed more help than anyone else. At the peak of the furore over this new ‘black magic’, the methods were looked into by Dr Rabi Mehta, a former teammate of Imran Khan in the 1990s. He went into the aerodynamics of the ball and came to the conclusion that “there was nothing particularly mysterious about the whole process; it just needed the ‘right kind of ball’, and the expertise to use it.”

Imran has acknowledged that he learnt how to use the ball so well from Sarfaraz, not to mention the famous use of a bottle cap. The Indian team was often at the receiving end of the ‘banana in-swingers’ from Imran in the early 80s, which he had first tried at Melbourne in January 1977, while Sarfaraz once took nine for 86 including, a spell of seven for one, at Melbourne in 1979.

But when Darrell Hair and Billy Doctrove pronounced Inzamam-led Pakistan guilty of ball-tampering at The Oval in 2006, it was the first time a team was thought to be in the wrong rather than individuals.

The pair of officials decided that the 56-over-old ball could not have been in such a state had it not been tampered with and thus invoked Law 42.3 to penalise the visiting side. Inzamam famously forfeited the Test match, though the result was reversed to a draw two years later.

In most theories of swing bowling, the exact roles of the leather, weather, action and seam can not be pinpointed conclusively because most tests are done indoors and not in match conditions. Also, no one can explain why a novice can at times extract more swing than an established bowler.

The mystery of swing and reverse-swing thus remains. As for ball-tampering, the attempts will continue, irrespective of how leather tastes.

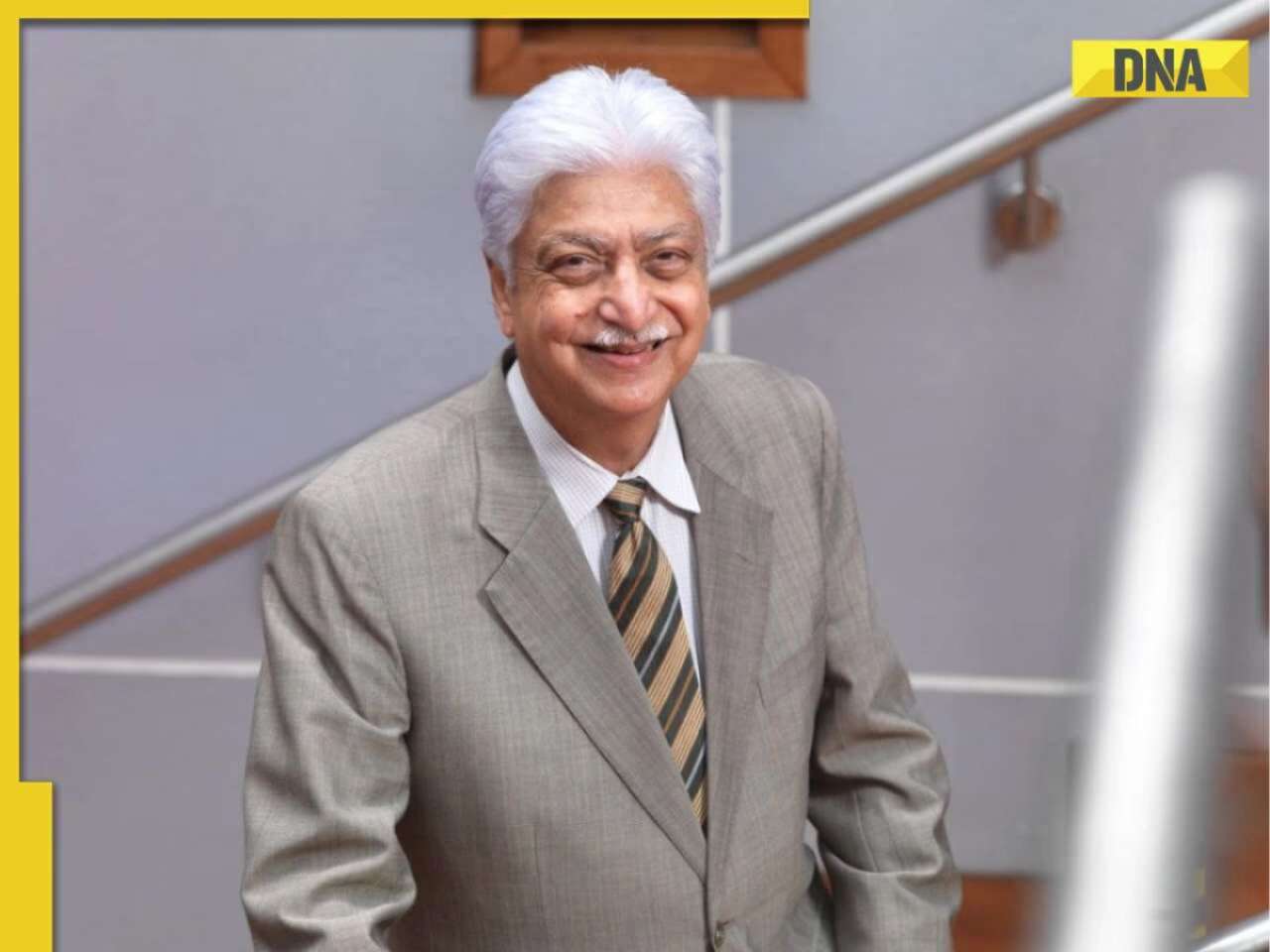

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)