Even seeing a game on television is difficult for many Afghans, with only about 14% of the country having regular electricity and most people outside Kabul watching games in groups or in outdoor communal settings.

The glitz of Sunday's World Cup final in South Africa will be a distant vision for millions of fanatical Afghan fans who will be glued to television screens dreaming of their country one day walking on soccer's big stage.

Although the game is immensely popular in Afghanistan, decades of conflict and a lack of development resources have left the country languishing in 189th place out of 202 in rankings administered by soccer’s world governing body FIFA.

"The government pays very little attention to football and to its players. We don’t have regular training," Mohammad Yaseen Mohammadi, deputy head of Afghanistan's national team, said.

"We have a long way to go before performing like other international teams in the world," he added.

Soccer is not alone of course. All sports have taken a back seat as Afghanistan struggles to overcome a worsening Taliban insurgency and the legacy of years of civil war which destroyed much of the country's sporting infrastructure.

Only Buzkashi has thrived, the violent polo-like national game in which players mounted on horses compete to get the carcass of a headless goat or calf over a goal line.

The Afghan national soccer team was founded in 1922 and joined FIFA in 1948. They play home games at the Ghazi National Olympic Stadium in Kabul, which was built by King Amanullah Khan in 1923 and holds 25,000 fans.

The ground has a bloody history. The Taliban used to execute condemned criminals or amputate the limbs of thieves at the stadium during their rule.

FIFA pays $250,000 -- less than the monthly wage of a player in one of Europe's big leagues -- to the Afghan authorities each year to cover player salaries and the administrative costs of branches in the country's 34 provinces, Mohammadi said.

"We can't pay much to good players who help the whole team win a game," he added. "The player considered a champion one year may have to leave football the next and work in a shop to feed his family."

Tell that to Portugal's Real Madrid winger Cristiano Ronaldo, who banks 11 million pounds ($16.71 million) a year as the world's highest paid footballer.

Afghanistan's top players need to hunt for wealthy backers like banks or powerful businessmen to feed their families as the government is unable to support them financially, needing to direct money into rebuilding since the Taliban’s 2001 ousting.

As Afghanistan's team rarely travels overseas for international matches, players see the opportunity to play for patron sponsors as the easiest income.

"Playing for the national team gives us a pride but nothing else, pride is not going to feed my family," said Hashmat Barekzai, Afghanistan’s 26-year-old captain, sporting the shirt of English Premier League club Arsenal.

"Football is my life but I need to earn money from it like professional players," he said sitting on the ground at Ghazi, which is the only grass soccer pitch in Kabul.

Barekzai earns about $1,000 a month from his sponsor, Kabul Bank, which is still 10 times the income of a government worker.

He always dreamed, he said, of Afghanistan playing in a World Cup, which he sees as a near-impossible task. The country's highest ever world ranking was 173 in July 2006.

"I will die, but my dream and hope will always live," Barekzai said.

Even seeing a game on television is difficult for many Afghans, with only about 14% of the country having regular electricity and most people outside Kabul watching games in groups or in outdoor communal settings.

But there have been small successes.

Afghanistan managed to beat India, neighbouring Pakistan and Sri Lanka in the group stage of this year’s South Asian Games men's soccer tournament before getting past the Maldives in the semi-finals and losing the final 4-0 to hosts Bangladesh.

According to the coach, the achievement lay in the passion of the players, and God’s mercy.

"No one expected that we would be able to make it to the final with our low morale and lack of resources," Elyas Ahmad Manocher said.

Manocher, recalled a phone call from the head of the Afghan Olympic team while he was in Bangladesh, begging for his team to at least beat fierce rivals Pakistan, which is often accused of treating Afghanistan as a puppet state.

"He said if the team lost to anyone else, it didn't matter," added Manocher.

Manocher, who earns $1,500 a month from his sponsor, said players are not usually allowed to train at Ghazi because the pitch is saved for top-tier matches, with the rest played on dust.

"How can you expect a national team to train and prepare on a dusty field? It is not even safe for our own health," he said.

![submenu-img]() House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins

House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins![submenu-img]() Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle

Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle![submenu-img]() Apple partners up with Google against unwanted tracker, users will be alerted if…

Apple partners up with Google against unwanted tracker, users will be alerted if…![submenu-img]() Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..

Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..![submenu-img]() Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?

Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?![submenu-img]() Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...

Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…

IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…![submenu-img]() Goa Board SSC Result 2024: GBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here

Goa Board SSC Result 2024: GBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here![submenu-img]() CUET-UG 2024 scheduled for tomorrow postponed for Delhi centres; check new exam date here

CUET-UG 2024 scheduled for tomorrow postponed for Delhi centres; check new exam date here![submenu-img]() Meet man who lost eyesight at 8, bagged record-breaking job package at Microsoft, not from IIT, NIT, VIT, his salary is…

Meet man who lost eyesight at 8, bagged record-breaking job package at Microsoft, not from IIT, NIT, VIT, his salary is…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'

Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins

House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins![submenu-img]() Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle

Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle![submenu-img]() Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..

Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..![submenu-img]() 'Ek actress 9 log saath leke...': Farah Khan criticises entourage culture in Bollywood

'Ek actress 9 log saath leke...': Farah Khan criticises entourage culture in Bollywood![submenu-img]() Bollywood’s 1st multi-starrer had 8 stars, makers were told not to cast Kapoors; not Sholay, Nagin, Shaan, Jaani Dushman

Bollywood’s 1st multi-starrer had 8 stars, makers were told not to cast Kapoors; not Sholay, Nagin, Shaan, Jaani Dushman![submenu-img]() Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?

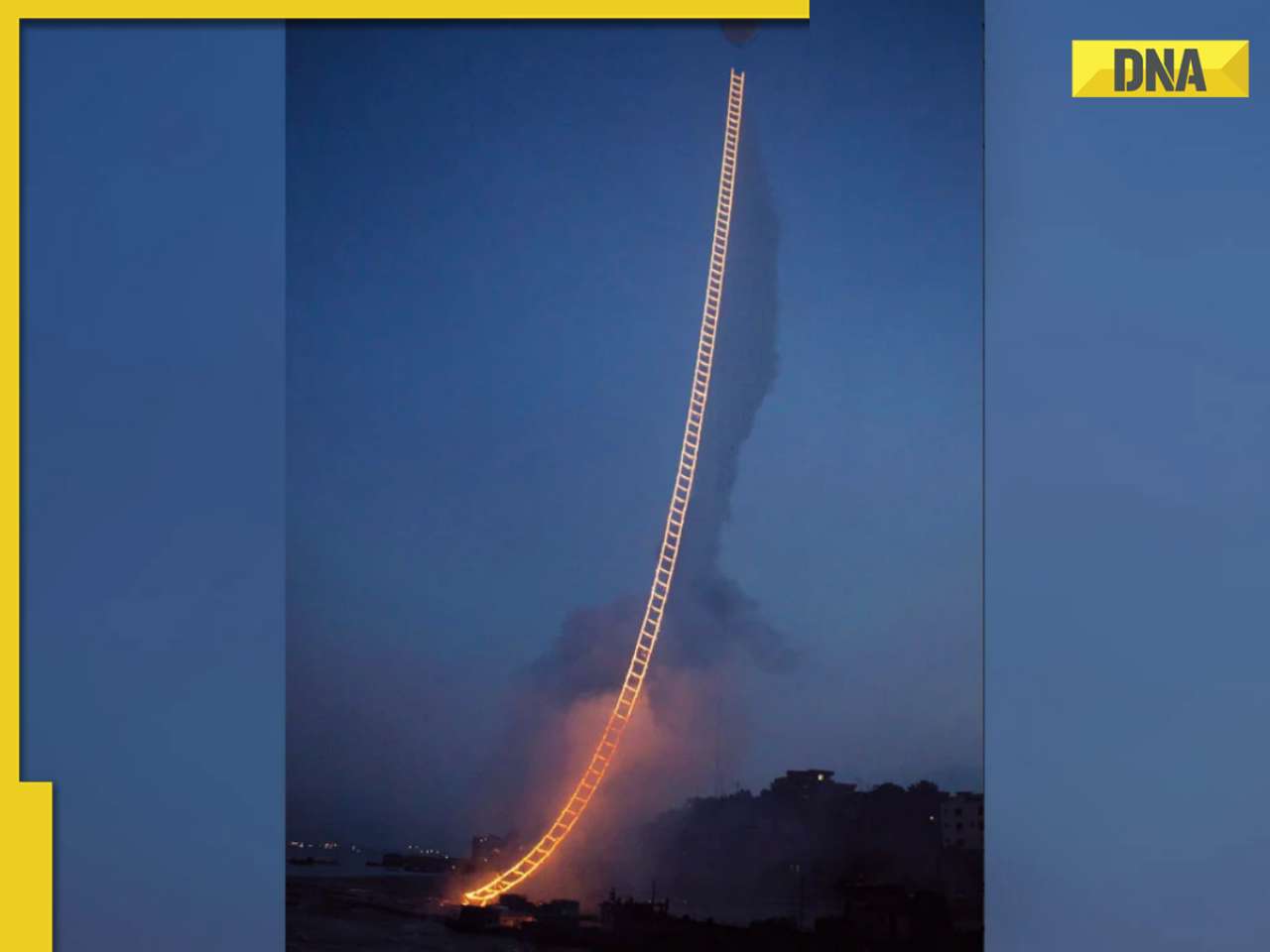

Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?![submenu-img]() Viral video: Chinese artist's flaming 'stairway to heaven' stuns internet, watch

Viral video: Chinese artist's flaming 'stairway to heaven' stuns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: White House plays 'Sare Jahan Se Achha Hindustan Hamara" at AANHPI heritage month celebration

Video: White House plays 'Sare Jahan Se Achha Hindustan Hamara" at AANHPI heritage month celebration![submenu-img]() Viral video: Bear rides motorcycle sidecar in Russia, internet is stunned

Viral video: Bear rides motorcycle sidecar in Russia, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Driver caught on camera running over female toll plaza staff on Delhi-Meerut expressway, watch video

Driver caught on camera running over female toll plaza staff on Delhi-Meerut expressway, watch video

)

)

)

)

)

)