In the spring of 1989, more than a million students & workers occupied Tiananmen Square in the Chinese capital and began the largest political protest in communist China’s history. Six weeks of protests ended with the massacre on the night of June 3. Exactly 20 years on DNA revisits.

On most spring days, Tiananmen Square in central Beijing, the world’s largest city square, hums with high-decibel life. Tourists from all over China and many parts of the world pose for pictures, adorable Chinese children fly kites or race around shrieking joyously, pesky salesmen peddle Mao Zedong memorabilia — and con artists size up prospective victims to ambush.

But for seven weeks in the spring of 1989, Tiananmen Square held the attention of a rivetted world not for its tourist attractions but for being the epicentre of one of the largest, most explosive and spontaneous demonstrations of “people’s power” that very nearly toppled the Communist Party regime that has ruled China since 1949.

1989 was a year of intense economic turmoil in China, adjusting itself to the consequences of post-Mao economic reforms: that year, inflation ran at over 30% and over a million factories closed down because of severe austerity measures.

Simultaneously, winds of change were blowing in the erstwhile Soviet Union, where Mikhail Gorbachev had ushered in a programme of economic reforms and political openness. In China, students who craved similar freedoms began a movement to commemorate a reformist leader, occupied Tiananmen Square, and demand speedier economic freedom and action against corruption. But such was the disaffection against the government that their actions set off a prairie fire of protests in over 400 cities, and triggered demands for democracy.

“It was a national uprising by a great many people who had different agendas, but many of them wanted to get rid of the Communist Party - and with good reason,” recalls journalist Jasper Becker, who reported on the Tiananmen Square movement of 1989.

The Communist Party was paralysed into inaction by internal division between conservative hardliners who pushed for a crackdown of the “counter-revolutionary riot”, and reformist-minded leaders who sought to open a dialogue with the student demonstrators. In the end, however, the hardliners won the day, and on the night of June 3-4, martial law troops forcibly evicted the students from the square. An estimated 2,500 people were killed that night in the area around Tiananmen Square, many of them Beijing residents who had put up roadblocks to thwart troop advances, and bystanders.

With blood on his hands, with the Communist Party’s legitimacy shot to pieces, and facing international condemnation for the massacre, China’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping embarked in 1992 on a bold economic reform that would transform China economically over the next 15 years. “It’s inconceivable that the Communist Party would have launched reforms if not for June 4,” reasons human rights researcher Robin Munro.

Twenty years on, though China has changed economically and socially, the ghostly memory of Tiananmen continues to haunt China’s authoritarian rulers. “Everything that happens in China today has the ‘Tiananmen effect’ written into it,” says China labour activist Vincent Kolo.

And the basic weaknesses in China’s party-state system that were revealed by Tiananmen “are still built into the system,” says Andrew J. Nathan, China scholar and co-editor of The Tiananmen Papers. “Whenever it hits a crisis, it can easily lose public support quickly since it doesn’t allow channels of dialogue with society.”

The power of one

One of the most inspirational scenes from the movement was played out on June 5, a day after the massacre. Troops had cleared Tiananmen re-established control.

As a column of tanks left the square, one solitary man holding shopping bags stepped onto the road and stood in front of the tanks. The tanks tried to get around him, but again & again he stood in their path, daring the soldiers inside to run over him. He even clambered onto it and banged on the turret before he was hustled away by residents concerned for his safety.

To this day, the identity of the man, known only as Tank Man, isn’t known. It was speculated that troops executed him, but that theory has been discounted. Whoever he was, the Tank Man’s act of defiance, which inspired protesters in Europe & USSR, represents a shining moment in the Tiananmen struggle, when one man confronted the power of a state —and triumphed.

Myths

Massacre: Tiananmen Square was the focal point of the student-led movement in 1989, but even independent investigators acknowledge there was no ‘massacre’ in the square on the night of June 3-4. There was a bloodbath, but much of the killings happened on the roads to the west of the square, when troops approaching Tiananmen found their way barricaded by residents and workers

Role of students: It’s true students initiated the movement, but it spread to all walks of life —industrial workers and trade unions, intellectuals, even housewives incensed by inflation. They didn’t always share the same goals and, in fact, student protesters went to great lengths to disassociate themselves from workers’ demands

The toll: Accounts of the number of people who died vary. Govt claims 241 deaths, including 218 civilians. Media reports spoke of 3,000 deaths. Students accounted for a small proportion; many of the dead were Beijing residents who blocked the troops from advancing — and bystanders

![submenu-img]() House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins

House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins![submenu-img]() Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle

Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle![submenu-img]() Apple partners up with Google against unwanted tracker, users will be alerted if…

Apple partners up with Google against unwanted tracker, users will be alerted if…![submenu-img]() Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..

Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..![submenu-img]() Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?

Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?![submenu-img]() Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...

Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…

IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…![submenu-img]() Goa Board SSC Result 2024: GBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here

Goa Board SSC Result 2024: GBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here![submenu-img]() CUET-UG 2024 scheduled for tomorrow postponed for Delhi centres; check new exam date here

CUET-UG 2024 scheduled for tomorrow postponed for Delhi centres; check new exam date here![submenu-img]() Meet man who lost eyesight at 8, bagged record-breaking job package at Microsoft, not from IIT, NIT, VIT, his salary is…

Meet man who lost eyesight at 8, bagged record-breaking job package at Microsoft, not from IIT, NIT, VIT, his salary is…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'

Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins

House of the Dragon season 2 trailer: Rhaenyra wages an unwinnable war against Aegon, Dance of the Dragons begins![submenu-img]() Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle

Panchayat season 3 trailer: Jitendra Kumar returns as sachiv, Neena, Raghubir get embroiled in new political tussle![submenu-img]() Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..

Meet actress whose debut film was superhit, got married at peak of career, was left heartbroken, quit acting due to..![submenu-img]() 'Ek actress 9 log saath leke...': Farah Khan criticises entourage culture in Bollywood

'Ek actress 9 log saath leke...': Farah Khan criticises entourage culture in Bollywood![submenu-img]() Bollywood’s 1st multi-starrer had 8 stars, makers were told not to cast Kapoors; not Sholay, Nagin, Shaan, Jaani Dushman

Bollywood’s 1st multi-starrer had 8 stars, makers were told not to cast Kapoors; not Sholay, Nagin, Shaan, Jaani Dushman![submenu-img]() Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?

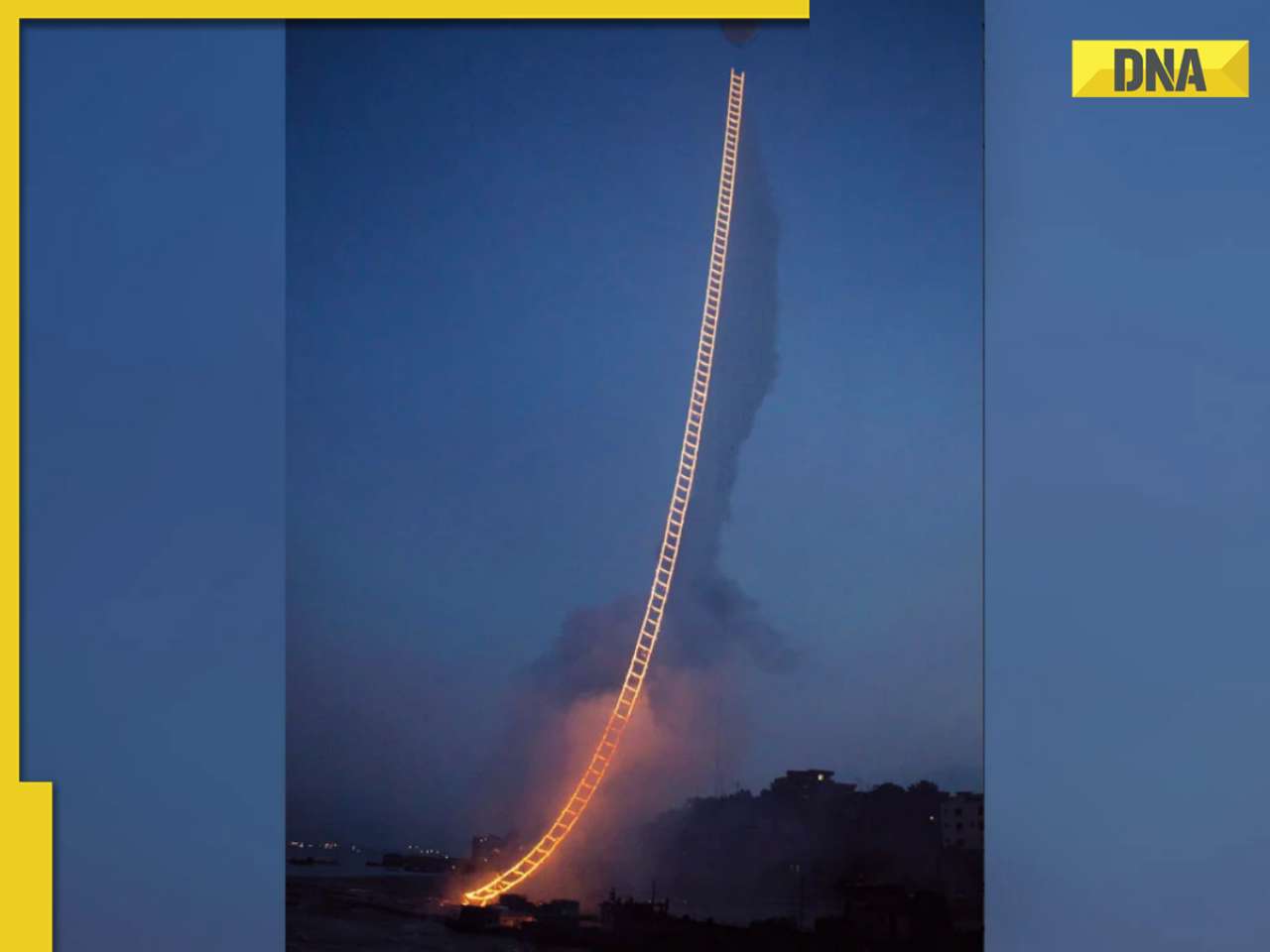

Who is the real owner of Delhi's Connaught Place and who collects rent from here?![submenu-img]() Viral video: Chinese artist's flaming 'stairway to heaven' stuns internet, watch

Viral video: Chinese artist's flaming 'stairway to heaven' stuns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: White House plays 'Sare Jahan Se Achha Hindustan Hamara" at AANHPI heritage month celebration

Video: White House plays 'Sare Jahan Se Achha Hindustan Hamara" at AANHPI heritage month celebration![submenu-img]() Viral video: Bear rides motorcycle sidecar in Russia, internet is stunned

Viral video: Bear rides motorcycle sidecar in Russia, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Driver caught on camera running over female toll plaza staff on Delhi-Meerut expressway, watch video

Driver caught on camera running over female toll plaza staff on Delhi-Meerut expressway, watch video

)

)

)

)

)

)

)