Two 100-year-old buildings; Kalbadevi’s Cotton Exchange and Watson’s at Kala Ghoda. One transformed to fit a new function, and preserved.

Old digs, new polish

Kalbadevi in south Mumbai is a perfect picture of chaos with a bevy of vehicles trying to make their way through a narrow strip of road. Along that busy stretch, at an intersection stands a beautiful nine-storeyed structure called the Cotton Exchange Building. Its façade is getting a facelift while the first three floors have been completely refurbished to house a jewellery mall. A fine example of the Art Deco movement, “it was the tallest building to come up during the 1930s construction boom,” says historian Sharada Dwivedi. The murals on the façade depict the journey of cotton from the fields to the centre of exchange.

The credit for turning it around — in what can be called ‘adaptive reusage’ — can be attributed to Arris Architects, a Thane-based firm. Cotton Exchange was a centre for auctioning various types of cotton and it housed the offices of various companies dealing in cotton. “Conservation had never been our core subject of practice; we just followed our instinct to bring back to life to this forgotten building. We took enormous efforts to clean the facade, hardly changing any of its earlier colours, murals and detailing. In some badly deformed areas we made use of glass-reinforced concrete to get back the original flavour,” says the 33-year-old director of Arris Architects, Shubhashish Modi.

Even though it was listed as a Grade II-A heritage structure, nothing much had been done to restore the building before the jewellery mall came up. “On our first visit alongwith the clients we saw a lobby with a very high ceiling made of Italian stone. It was in a big mess,” confides Modi. The floor and the walls of the lobby are now made of Italian marble. The ground, first and second floors are made of imported white marble.

But the floors above still wear a dilapidated look. The walls along the staircase are stained with betelnut juice, electric wires hang dangerously from the ceiling.

The jewellery mall will be open to the public around the end of this month.

History, unprotected

Every working day is a busy day in the Watson’s Hotel building, also known today as Mahendra Mansion, in Kala Ghoda. Lawyers in black-and-white uniforms can be seen making hasty exits from the building on their way to the court building behind Watson’s. Students, labourers, tenants and travellers crowd around the photocopier shops. Watson’s Hotel has experienced a transformation from a posh 19th century English hotel to an overused commercial building.

Watson’s stands out like a sore thumb next to the appealing neo-classical Army Navy building and the gothic Bombay University, because of its stark look. Its once impressive iron beams look mouldy due to lack of maintenance.

It is hard to believe that this was once a grand hotel (where Jamshetjee Tata was denied entry, goes the tale, leading him to build the Taj) erected between 1867-69 by John Watson, a wealthy city draper. The result of a 19th century architectural experiment when pre-fabricated buildings made an appearance in England, Watson’s is Mumbai’s sole example of this experiment.

On the ground floor, the photocopier shops, the dingy eatery and an unused office belonging to Air India have replaced the once-bustling wine cellars, a commodious bar and a ballroom of a bygone era. The atrium or the ballroom with a transparent glass ceiling is in a shambles. And the public hall in Watson’s, where the Lumiere brothers premiered their films in July 7, 1896 has been long been forgotten.

Signs of decay are everywhere. The building was included in the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the New York-based World Monuments Fund (WMF) in 2005. Since then two of the balconies in the western wing have collapsed due to pressures of overcrowding, says conservation architect Vikas Dilawari who has restored the contemporary Army Navy building in Kala Ghoda.

Several temporary wooden poles are holding up the roof on the first two floors. Seeing the decaying building and being unable to help conserve it is frustrating for the conservationist architects in Mumbai. MHADA has taken measures to restore the building by plastering some of the weak walls. “But that has been of no use,” says Dilawari, “the plaster keeps peeling due to humidity.”

“If you want the building to have a future, you must conserve it today,” says Harshad Bhatia, urban designer and a member of the Indian Institute of Architecture. “The structural integrity of the building should be maintained as close to the original with only the damaged portions replaced by material similar in colour and texture to the original construction material.”

Architects are often in a fix while restoring near-destroyed buildings if they should conserve the authentic style or improvise on the form to accommodate the need of the building in its present context. At present the Watson building houses over 150 tenants (according to a tenant who does not want to be identified). Most of them live in one-roomed tenements. For Bhatia, “It is important for the restored building to have a function similar to the original intended use or adaptive to the restored space.”

Although it is believed that all man-made structures are not irreplaceable and new creations mark the beginning of a new era, yet, letting go of a unique architectural creation is painful for any society. According to BV Doshi, a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects and the founder of Ahmedabad-based Vastu Shilpa Foundation, “Every building should be preserved because once a creation is lost, you cannot get it back.”

![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax

Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() Akshaya Tritiya 2024: Know date, timings, puja vidhi and significance

Akshaya Tritiya 2024: Know date, timings, puja vidhi and significance ![submenu-img]() Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy

Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy

Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy![submenu-img]() Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’

Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’![submenu-img]() Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive

Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() This actress was forced to work in B-grade films, called ‘ugly duckling’; became superstar, now owns Rs 100 crore house

This actress was forced to work in B-grade films, called ‘ugly duckling’; became superstar, now owns Rs 100 crore house![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets

IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru![submenu-img]() Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral

Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked

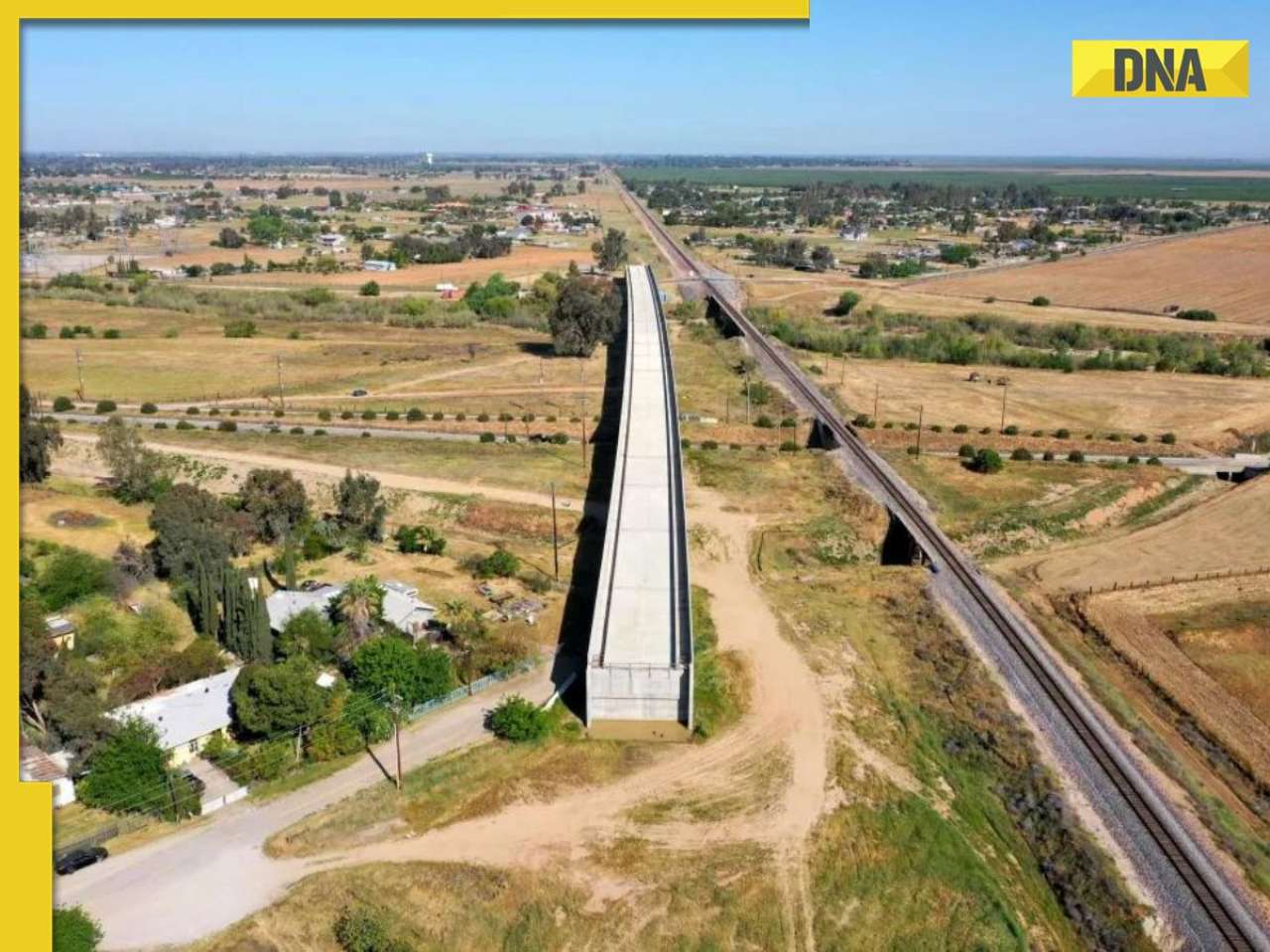

Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked![submenu-img]() This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why ![submenu-img]() Not Alia Bhatt or Isha Ambani but this Indian CEO made heads turn at Met Gala 2024, she is from...

Not Alia Bhatt or Isha Ambani but this Indian CEO made heads turn at Met Gala 2024, she is from...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)