China and India have grown economically and politically in stature over the last two decades.

China and India have grown economically and politically in stature over the last two decades. “The rising economic and political power of Asia is the biggest story of our times,” writes Bill Emmott in his latest book Rivals: How the Power Struggle Between China, India and Japan will Shape Our Next Decade. From 1993 until March 31, 2006, Emmott was the editor of The Economist, the world’s leading weekly magazine on current affairs and business. He has now stepped down from that post to become an independent writer, speaker and consultant, based in London and Somerset. In this interview with Vivek Kaul, he talks about the economic and social changes that China and India are destined to go through in the days to come.

Lately there has been a deluge of books on India and China. Nevertheless, this seems to be the first book that talks about India, China and Japan at the same time. What made you write this book?

I lived in Japan during the 1980s and have written books about it, so I was very familiar with that country. At first, I thought I might write about the tension between China and Japan, but then as I studied further I realised there was a bigger story going on, with Japan and the United States trying to get friendlier with India in order to balance China’s growing influence in Asia, and with India too increasingly keen on exerting its influence across the whole of the region.

So I decided to take a look at the big picture in the politics and economics of Asia, rather than just at one country or another. Also, I should confess that I am instinctively something of a contrarian. When everyone is focusing on one particular thing (in recent years, the rapid growth of China and India, and the idea that this is something of a “threat” to the West), I tend to go the other way, and try to see whether that conventional wisdom might, in fact, be wrong. In a nutshell, what I conclude in my book is that the growth in Asia is not at all a question of “East vs West”, as so many American and European writers term it. Instead it is a question of “East vs East”, in other words of rivalry between the three great powers of Asia itself.

Till 2001-02 prices of various commodities had been declining. However, since then, the prices have been on their way up. What do you think are the reasons for the same?

It is a question of supply and demand. Thanks to falling prices in the previous two decades, there was little investment in new mines, oil fields and so on. Now, with China industrialising so fast and building its infrastructure, and with India beginning to do the same, the demand for these commodities has been growing rapidly. Supply cannot keep up. I think this will go on for a while longer, as it takes time to build new mines and oil rigs, but eventually supply will catch up and prices will fall.

Lately both China and India ( to some extent) seem to have given up moral pretensions on when it comes to investing in Africa or for that matter even in Myanmar. Why do you think that this is happening? In a race to get hold of various commodities (primarily oil) do you see India and China getting into a joint arrangement while bidding, like they have in Sudan?

Both governments are operating purely in their country’s national commercial interests. Moral considerations, about democracy and human rights, have been dumped. That is not surprising for China, but it has been quite surprising in India’s case. Nevertheless, this change is permanent. I don’t expect India to resume its moral policy any time soon. Sometimes joint arrangements will make sense, but mostly Chinese and Indian firms prefer to work on their own, so that they are in control.

In the past whenever the price of oil has risen rapidly, it has led to oil shocks. Why do you feel that is not happening currently?

This year, oil-price inflation will, I think, lead to a global economic slowdown. Indirectly, it will even force both India and China to slow down, as both countries need to clamp down on overall inflation. It has taken time, but I think finally the oil price is going to have a real economic impact in consuming countries like the West, China and India. The shock is about to come.

No country is more diverse than India — and which works against on growth. Given the various schisms in the country of caste, religion and class, levels of trust are obviously low — making it more of a problem in terms of governance. Every group wants its own people and does not trust anyone else. What are your observations on this? In addition, do you feel that Indian democracy is coming in the way of India’s development?

I don’t agree that diversity is an obstacle to growth. Why shouldn’t it, in fact, be a strength, with groups competing and with so many different sources of ideas, enterprise and energy? The real obstacles are lack of trust, yes between groups but also a lack of trust in politics and government at all levels. In China, there is a deep suspicion about the government but at least people believe the government is likely to be consistent and quite strong. In India, the problem is that governments change their minds all the time and that trust in politicians is so low, as so many have criminal records and are corrupt. This is not a question of democracy vs dictatorship, it is a question of credibility, effectiveness and trust. As for India’s growth rate, I believe that with a credible, trusted set of government institutions the rate could be as high as 12-15%, as the potential is so large. The sacrifice made for lack of trust, ineffective institutions and lack of reform is that growth is only 7-9% (please note that I believe the range is now 7-9% not 8-9%).

China has largely fixed the rate of the renminbi to the dollar. How does that help?

The artificially low value for the renminbi has helped boost China’s exports, especially of manufactures, just as a cheap yen boosted Japanese exports during the 1960s. But China has paid a price for that, since it kept the renminbi artificially low the central bank has to keep buying dollars using renminbi, which is why its foreign-exchange reserves have now reached $1.7 trillion (India’s are $220 billion or so). This poses an increasing danger of inflation in China. I believe the Chinese will soon decide to revalue the renminbi in order to prevent inflation from getting out of hand. The result will be a sharp slowdown in Chinese growth, perhaps even a temporary slump. And at that time, there will be a big danger of protests from workers who lose their jobs.

China currently has both a real estate as well as a stock market bubble. Do you see that changing in the days to come?

The Shanghai stock market has already fallen by 50% since January this year. I think that this will continue, as the authorities need to restrict money supply in order to control inflation and to revalue the currency, meaning less money is available for speculation in stocks. Eventually, this will also start to bring down real estate prices, although I don’t believe there has been such a bubble in property.

Which one out of India and China do you think will win the race? Do you see any chance of China becoming a democracy?

China is about 15 years ahead of India, with an economy almost three times bigger than India’s. So it will be very hard for India to catch up or overtake China any time soon. Nevertheless, I think during the next decade, India’s growth will start to become faster than China’s with the result that the gap will gradually get narrower.

I think that as China’s urban middle class grows, the pressure for some sort of democracy will become irresistible. This will become a big issue within the next decade.

Do you feel that the one child norm that China has been following in its cities will start to hurt sometime?

If you have a lot of young people it reduces your labour costs. That helped China during the 1990s, but now thanks to its one-child policy of family planning China is running out of young people. The result is that Chinese wages are rising quite rapidly, and China needs to move upmarket to higher value, higher technology activities.

What are the major things that India can learn from China when it comes to execution?

One thing is that India should not be afraid of lowering its trade barriers: China executed that policy in the late 1990s and has profited from it as it forced reform. Another is that the most vital contribution of the government is to speed up infrastructure investment, especially in electric power, roads and ports. Without that, other development cannot and will not follow.

How do you see India and China balancing growth with environmental concerns that come with it?

It depends chiefly on public opinion in both countries. The Chinese public, especially in cities, is now getting angry about pollution, and I think that is going to force the Chinese government to control pollution more effectively and this to achieve more balanced growth.

In India, public opinion is less angry about pollution in general, so I don’t believe the pressure to deal with environmental problems is as strong as it is becoming in China. The reason is that India is so much poorer.

k_vivek@dnaindia.net

![submenu-img]() Ramesh Awasthi: Kanpur's 'Karma Yogi' - Know inspirational journey of 'common man' devoted for society

Ramesh Awasthi: Kanpur's 'Karma Yogi' - Know inspirational journey of 'common man' devoted for society![submenu-img]() Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'

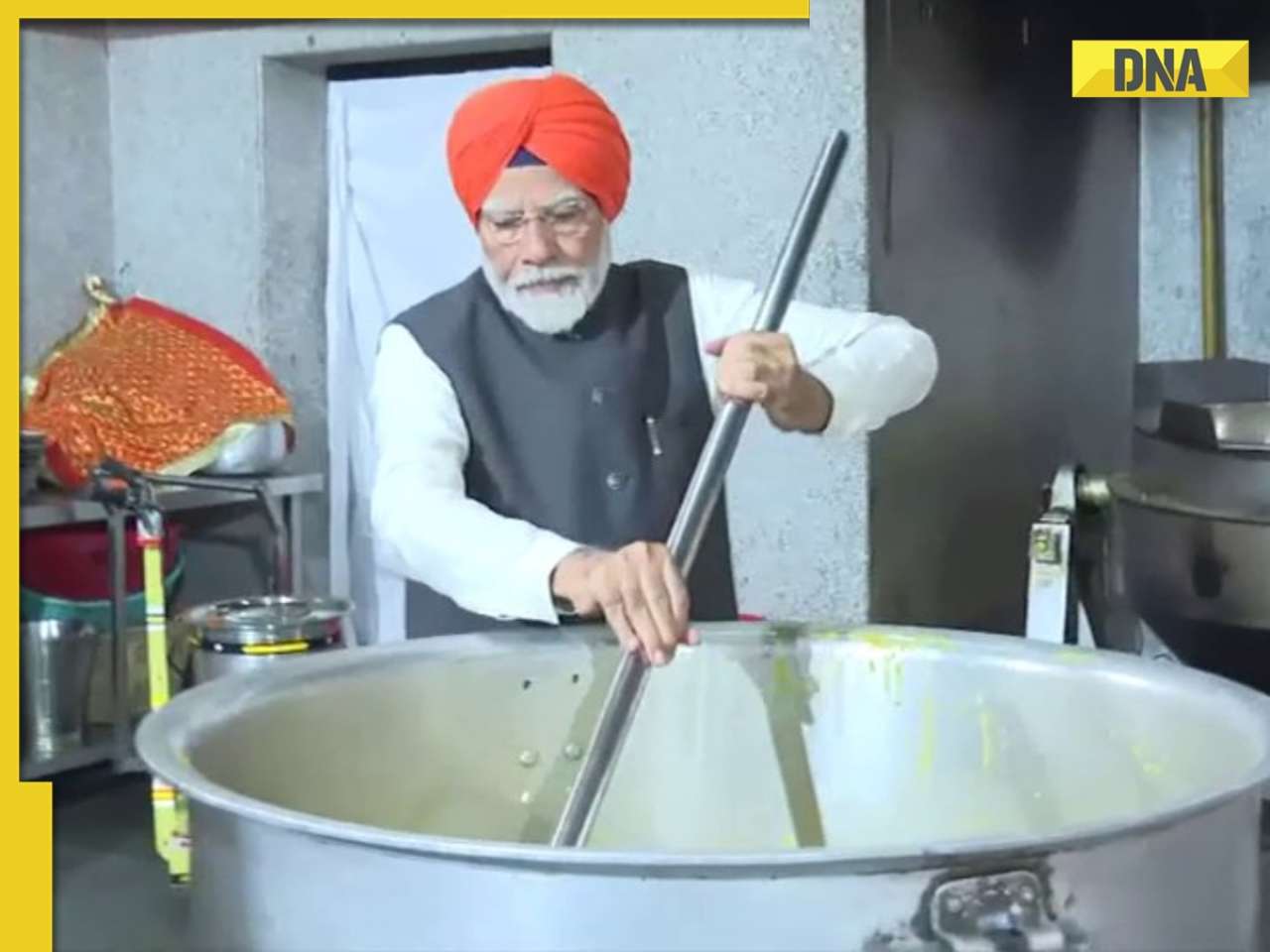

Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'![submenu-img]() PM Modi wears turban, serves langar at Gurudwara Patna Sahib in Bihar, watch

PM Modi wears turban, serves langar at Gurudwara Patna Sahib in Bihar, watch![submenu-img]() Anil Ambani’s debt-ridden Reliance’s ‘buyer’ now waits for RBI nod, wants Rs 80000000000…

Anil Ambani’s debt-ridden Reliance’s ‘buyer’ now waits for RBI nod, wants Rs 80000000000…![submenu-img]() Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious

Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious![submenu-img]() Maharashtra Board HSC, SSC Results 2024: MSBSHSE class 10, 12 results soon at mahresult.nic.in, latest update here

Maharashtra Board HSC, SSC Results 2024: MSBSHSE class 10, 12 results soon at mahresult.nic.in, latest update here![submenu-img]() Meet IIT-JEE topper who passed JEE Advanced with AIR 1, decided to drop out of IIT due to…

Meet IIT-JEE topper who passed JEE Advanced with AIR 1, decided to drop out of IIT due to…![submenu-img]() Meet IPS Idashisha Nongrang, who became Meghalaya's first woman DGP

Meet IPS Idashisha Nongrang, who became Meghalaya's first woman DGP![submenu-img]() CBSE Results 2024: CBSE Class 10, 12 results date awaited, check latest update here

CBSE Results 2024: CBSE Class 10, 12 results date awaited, check latest update here![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was denied admission in IIT due to blindness, inspiration behind Rajkummar Rao’s film, now owns...

Meet man, who was denied admission in IIT due to blindness, inspiration behind Rajkummar Rao’s film, now owns...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'

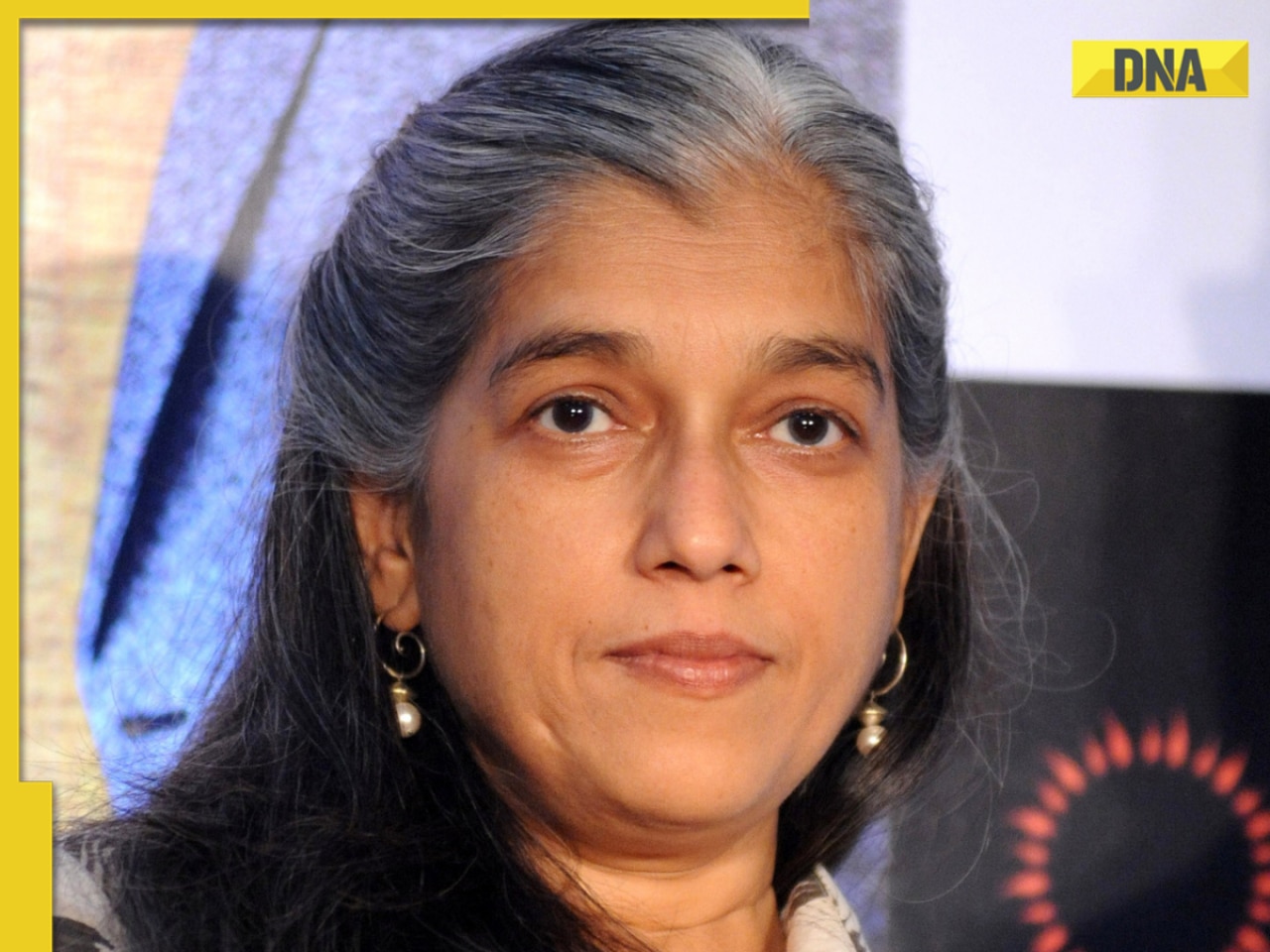

Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'![submenu-img]() Ratna Pathak Shah calls Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy's films 'offensive', says, 'women are constantly...'

Ratna Pathak Shah calls Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy's films 'offensive', says, 'women are constantly...'![submenu-img]() Shreyas Talpade recalls how he felt bad when his film Kaun Pravin Tambe did not release in theatres: 'It deserved...'

Shreyas Talpade recalls how he felt bad when his film Kaun Pravin Tambe did not release in theatres: 'It deserved...'![submenu-img]() Anup Soni slams his deepfake video from Crime Patrol, being used to promote IPL betting

Anup Soni slams his deepfake video from Crime Patrol, being used to promote IPL betting![submenu-img]() Real story that inspired Heeramandi: The tawaif who helped Gandhi fight British Raj, was raped, abused, died in...

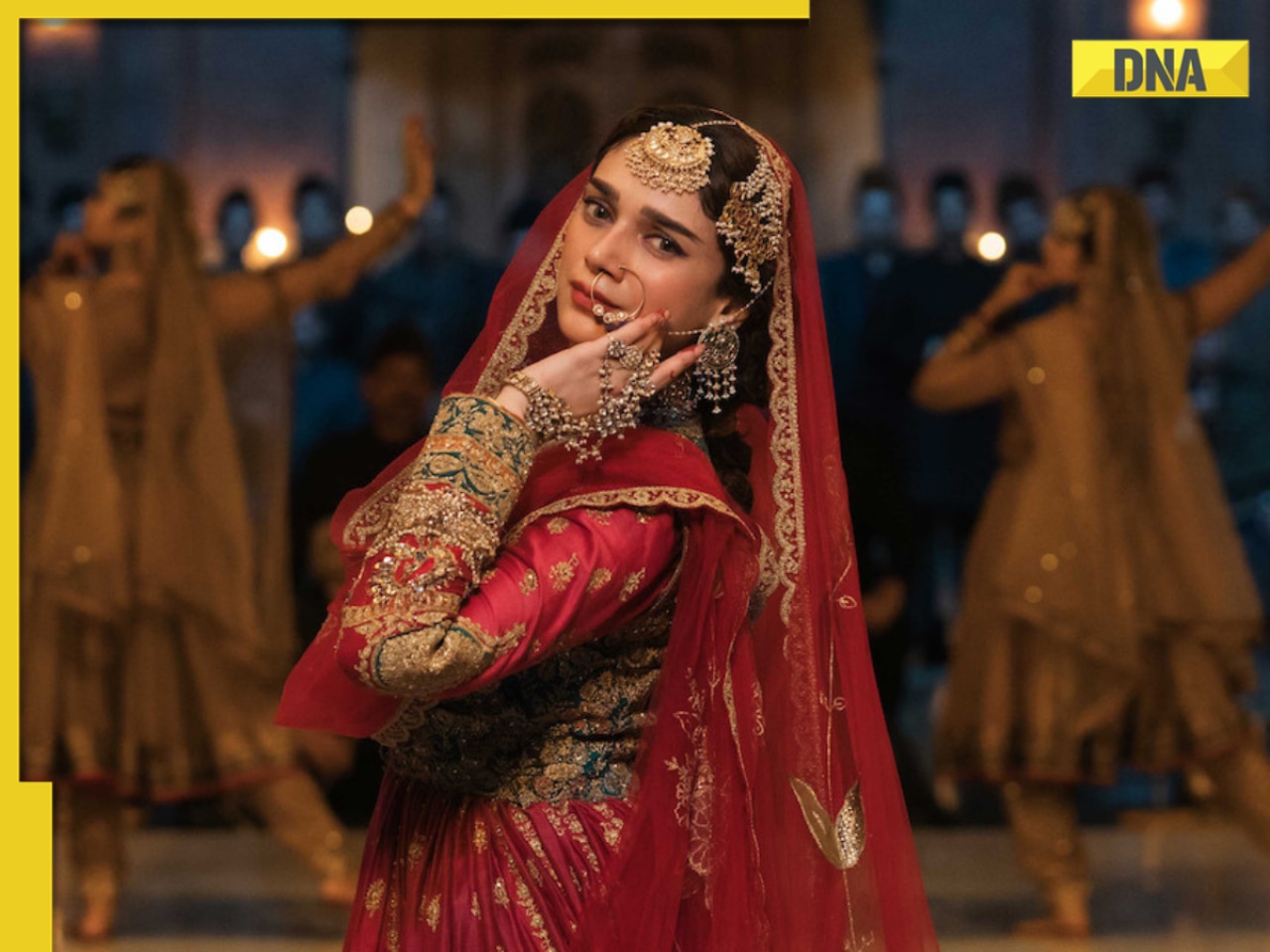

Real story that inspired Heeramandi: The tawaif who helped Gandhi fight British Raj, was raped, abused, died in...![submenu-img]() Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious

Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious![submenu-img]() Lift collides with roof in Noida society after brakes fail, 3 injured

Lift collides with roof in Noida society after brakes fail, 3 injured![submenu-img]() Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal invites employees' moms to office for Mother's Day celebration, watch

Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal invites employees' moms to office for Mother's Day celebration, watch![submenu-img]() This clip of kind woman feeding rotis to stray cows will bring tears of joy to your eyes, watch

This clip of kind woman feeding rotis to stray cows will bring tears of joy to your eyes, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Seagull swallows squirrel whole in single go, internet is stunned

Viral video: Seagull swallows squirrel whole in single go, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)