Countries must construct their foreign policy within the context of the overarching geopolitical landscape or fail in their goals.

Deborah Nutter

Geopolitics no longer disadvantages India. This is the great difference between 1947 and today. Countries must construct their foreign policy within the context of the overarching geopolitical landscape or fail in their goals.

It is not that most states do not have opportunities or choices open to them; it is that their choices are constrained by the international and regional geopolitical landscape.

When that landscape changes, states must recalibrate their orientations and their policies toward the outside world. For India, this is the moment not only of recalibration but of great opportunity on the world stage.

India — spanning almost an entire sub-continent, the largest and strongest state on that sub-continent, strategically located astride the Indian Ocean to both its east and west; connected by these waters to the Persian Gulf, the Middle East, and the world as a whole; large and populous; endowed with an ancient civilisation and great natural and human resources, its people located all over the world — has until now only once (during the Mughal empire) played a large and independent role in international politics.

For most of the years since August 1947, when it declared its Independence, India’s dreams were constrained by a disadvantageous geopolitical landscape.

Today, as it celebrates the 60th anniversary of its Independence, the international landscape is immeasurably more conducive to a strong and influential role for India, not only in Asia, but in the world as a whole.

Indian Independence occurred in the context of a world geopolitical shift of seismic proportions. The year 1947 marked not only the end of British rule in India, but also the end of British power worldwide and the beginning of the Cold War.

It was the pivotal year in the largest shift in world power since the second half of the 19th century, which saw the rise of the United States and Germany.

In August of 1947 the focus of the world was not on India, but on events in Eastern Europe, as one East European state after another moved into the Soviet orbit. Sixty years later this is no longer the case: the world is focused on India.

The geopolitics of the Cold War precluded India from playing the important and influential role in Asia and world affairs that Nehru had envisioned.

The parameters of its foreign policy were determined less in New Delhi than in Washington and Moscow. Instead of Asia left to Asians — and perhaps to India — the United States, for the purpose of containing the Soviets, stepped into the areas vacated by the British and assumed a predominant role.

This involved alliances throughout Asia, including one with Pakistan. Under these conditions, India chose neutrality, albeit a neutrality tipped toward Moscow.

A relationship with Moscow, less involved in Asia, and with a history of anti-imperialism and socialism, was more compatible with India’s goals.

While India was able to play a leading role in the non-aligned movement, facilitate international negotiations, and achieve a ‘soft power’ reputation, its ability to play a larger international role was circumscribed, and socialism was unable to unleash the economic potential and capacities of the country.

In 2007, as India celebrates the 60th anniversary of its Independence, the world is again in the midst of seismic changes. But this time, unlike 1947, India is one of the engines of change. What happens here affects us all.

Since 1979, when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, India had undergone a slow rethinking of the alliance with the Soviets. The Soviet collapse and implosion of its sphere of influence during 1989-1991 and the resultant era of globalisation — while initially disorienting — caused India to liberalise its economy, putting it in a position to leverage its strategic location and its many other attributes.

Now India finds itself poised to be one of the great economic and military powers of the 21st century. The current unipolar world is making way for one in which there will most likely be three or more great powers.

In this emerging world, India and the US have much in common: a desire for stability in Asia, a tradition of democratic government, a mutual concern with terrorism, and the use of the English language.

But India and the United States are also divided on several issues, among them, disagreements over Iran, trade conflicts that will continue to arise, the disconnect over Pakistan, and nuclear proliferation, which touches on deep identity and security fears of both sides. Will the relationship be able to withstand the inevitable problems? The rise of the power of the United States and Germany at the end of the 19th century caused the British to pursue a policy of accommodating the interests of its former enemy, the United States. It was a bumpy and contentious road at times, but the British persisted and were successful in creating a partnership that worked well for both. Now the US and India must do the same.

But what about China, the other emerging giant? Must the Indian-US relationship be against or preclude China? That is where we should be happy that history does not have to repeat itself. The rise of both powers can be peaceful.

The world, facing severe challenges in this century — global warming, nuclear and conventional arms proliferation, terrorism, pandemics, poverty, HIV/AIDS — does not need another Cold War or to have the United States, China, and India at odds with one another. The stakes are too high.

Fortunately, unlike a bipolar world, a world of three or more great powers should allow for flexible and positive relations among them all.

That, at least, two of the great powers will be strong and stable democracies, that, for all their faults, have the capacity to self-correct, is a good thing.

Geopolitics 60 years after Independence appears to favour India — and perhaps the world. And it is hard to trump geopolitics.

Deborah Nutter is Professor of Practice, Fletcher School/Tufts University

![submenu-img]() Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...

Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...![submenu-img]() 2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…

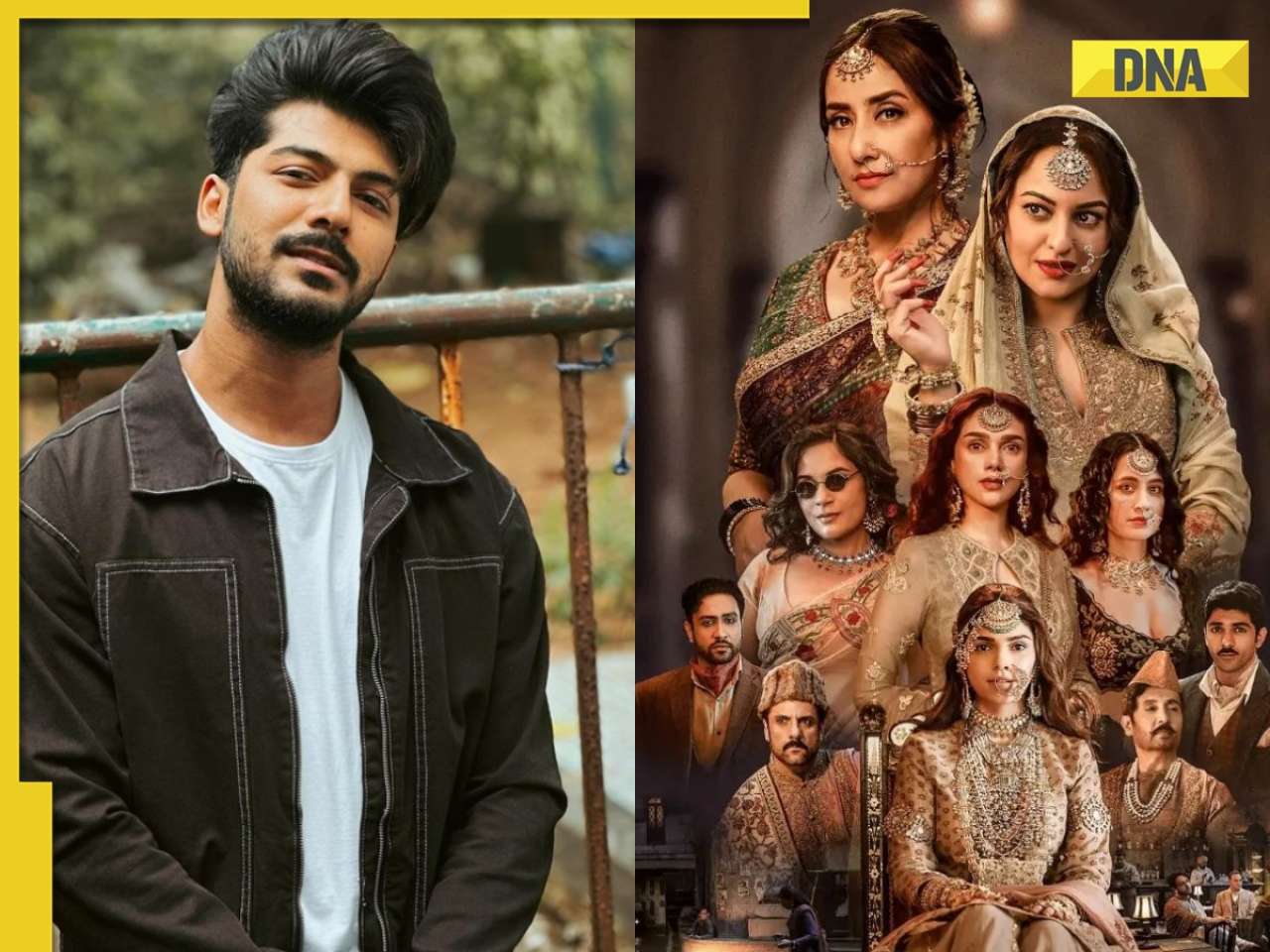

2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…

Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…![submenu-img]() Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police

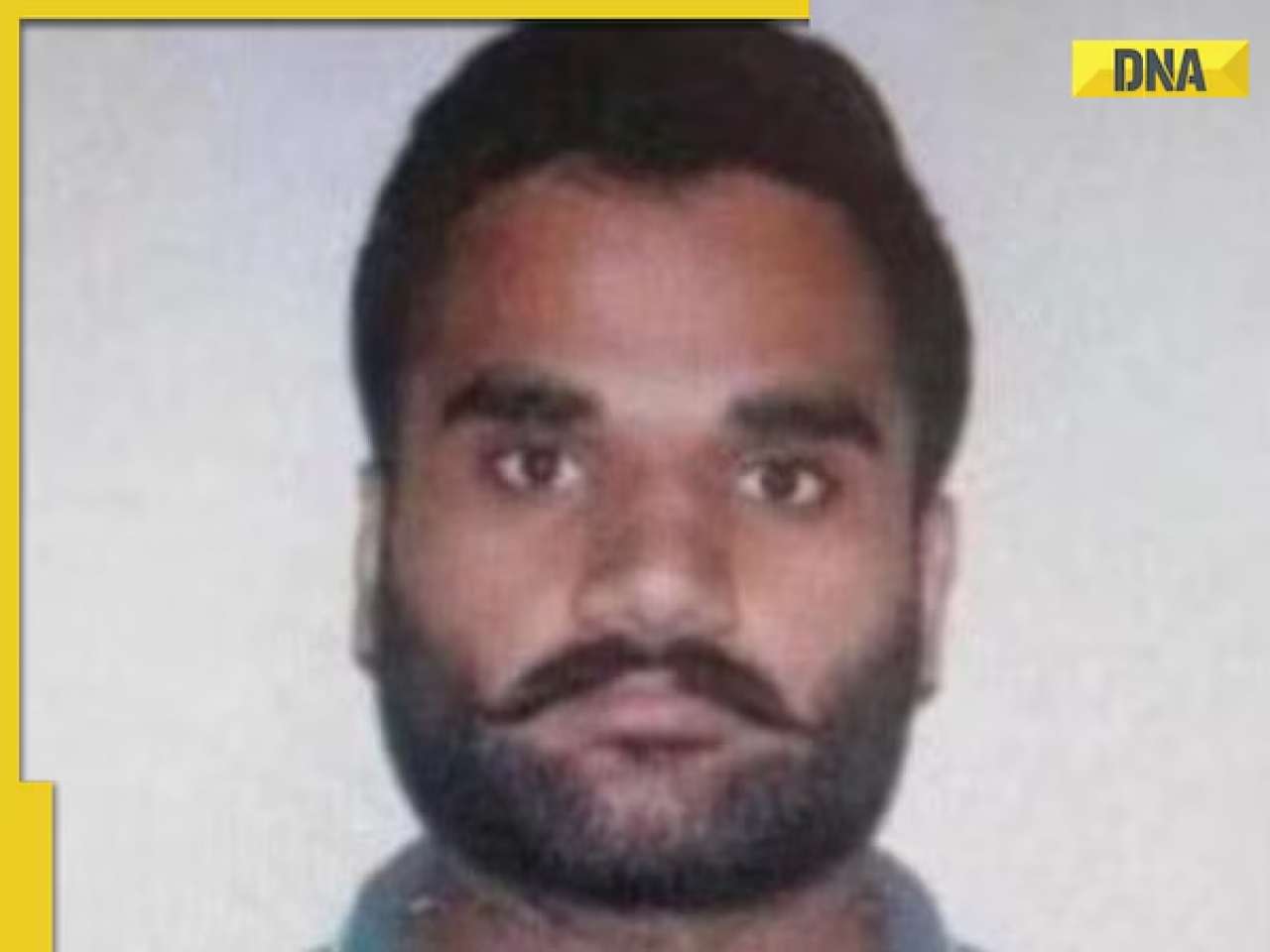

Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..

Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’

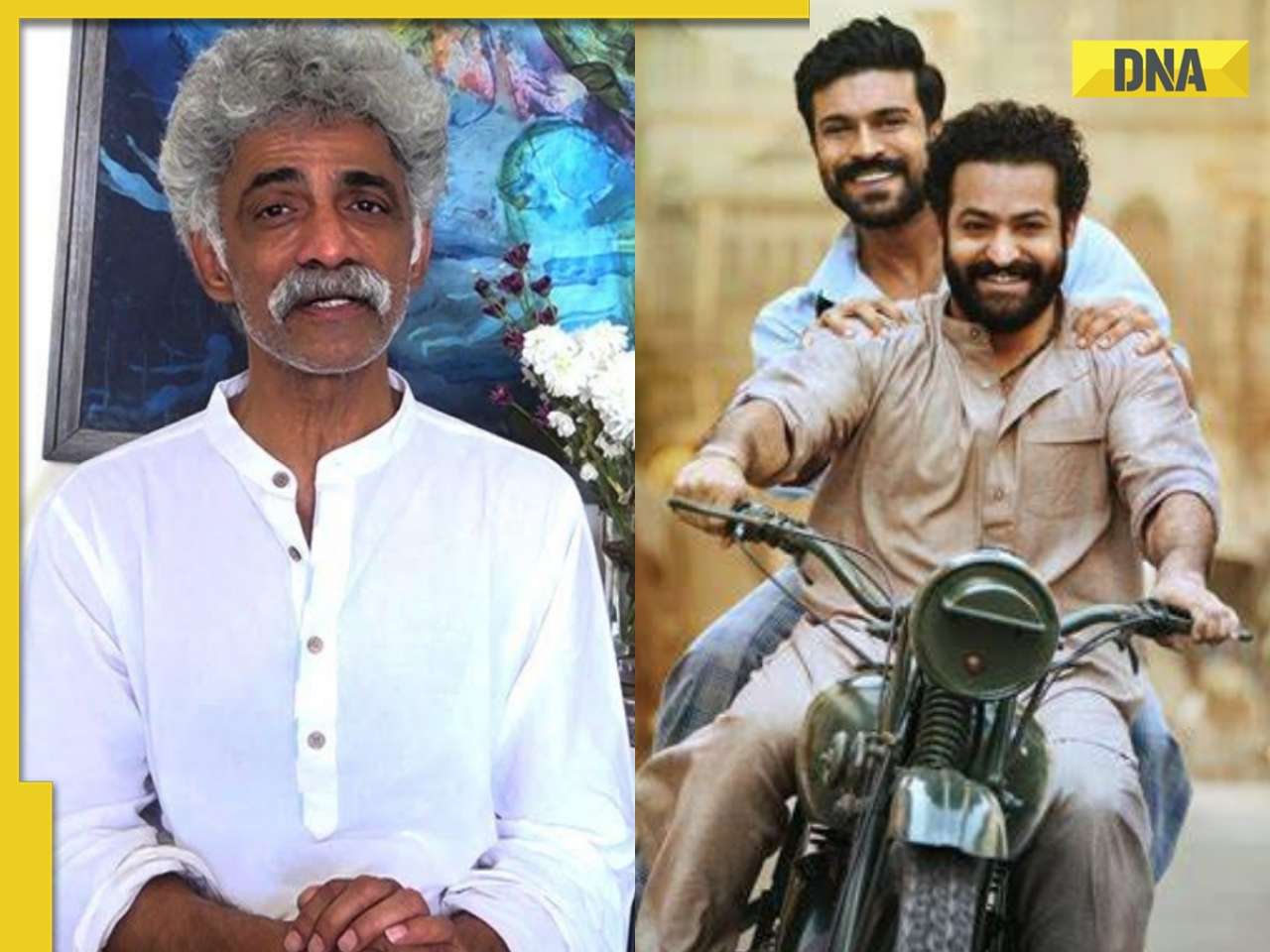

Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’![submenu-img]() Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...

Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...![submenu-img]() Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore

Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets

IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets![submenu-img]() Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here

Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals

SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch

Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch

Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts

Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet

Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet![submenu-img]() Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)