Indicatively, by 2005-end - before the start of the bull run - total stock holdings by Chinese households and firms accounted for only 10% of domestic financial wealth .

HONG KONG: When the Shanghai stock index skipped a heartbeat on Thursday, after its gravity-defining run in recent weeks, the question popped on the minds of many China watchers: is this the dreaded beginning of the end? And will a meltdown in China drag down markets across the world, as it did in February?

By the end of the day, the market had lost half a percentage point, unnerved by former US Fed chairman Alan Greenspan’s grim warning overnight of a “dramatic contraction” in Chinese stock valuations. But although the day’s loss was barely a blip when seen against the phenomenal 55% appreciation this year (on top of a 130% gain last year), game theorists are increasingly drawing up worst-case “what if” scenarios to map China’s post-meltdown landscape.

Yet, curiously, for all the froth that is manifestly floating around China’s stock market, the prognosis - in even the worst-case scenario - appears to be reasonably sanguine for China’s economy, which has shock absorbers to ride out any turbulence.

“Even a significant domestic equity market correction - for instance, a 30% erosion in valuations in a short period of time - will have little or no impact on the rest of China’s economy,” asserts UBS chief Asia economist Jonathan Anderson. “That’s because the tradable equity market is still a very small part of wealth holdings in China.”

Indicatively, by 2005-end - before the start of the bull run - total stock holdings by Chinese households and firms accounted for only 10% of domestic financial wealth (against an average of 38% for emerging Asia). And although that proportion shot up to 25% in China by April 2007, reflecting the sharp rise in stock values, it’s still well below the regional and global average, says Anderson. “Keep in mind also that the bull run from 2005 up to now has added only around 15% to financial wealth in the economy - which means that a 30% market correction going forward would entail a financial loss of only 8% wealth holdings.”

There’s one other statistic to consider while estimating the downside in the event of a meltdown: more than two-thirds of China’s A Share market is still locked up in illiquid, non-tradable state shares. Unlike the non-free floating portion of other global markets, these shares are “owned” neither by households nor the corporate sector. “If we restrict ourselves to ‘liquid’ financial wealth - that is, using free-float market capitalisation, which is the way actual households and firms would look at their financial holdings - it turns out that free-float A shares account for only 11% of domestic financial wealth today,” adds Anderson. “Clearly, even a very large correction would hardly make a dent in total liquid wealth.”

Even after the dream run of the past year and a half, China’s equity market is still very small: total market capitalisation accounts for only about 20% of GDP. (In India’s case, for example, it is almost twice that.)

There is also reason to argue that a meltdown won’t impact consumer spending, reasons Anderson. That’s because although consumption spending - as reflected in real retail sales - has been growing steadily since 2004, there hasn’t been any correlation with the “bull market”. For instance, there’s no sign of any further jump in the past two to four quarters as the share market soared.

Likewise with fixed-asset investment; it accelerated in mid 2005 when the government eased restrictions and injected more liquidity into the economy, but in the past 12 months, when the market was rising, fixed-asset investment actually slowed down.

What this means, reasons Anderson, is that there’s no consumption boom to reverse: just as there was no spending response when the market was going up, there may not also be a spending response when it heads down. Turn to Page 23

And in his reckoning, even the extent of debt taken on by households and firms to invest in equity isn’t heavily skewed. “On the one hand, it seems clear that more leverage has come into the stock market in the past quarter or two, but on the other there’s nothing to suggest that the market is heavily geared. Indeed, the best-available evidence points to a predominantly retail interest driven by portfolio reallocation out of existing deposit savings and into equities.”

Noting that there had been at least four daily sessions this year when the Shanghai index dropped by 5% or more, Anderson recalls that in every case, prices rebounded immediately, with no sign of the kind of “knock on” selling to cover leveraged long positions that one normally sees in highly geared markets. “All this, taken together, leads us to conclude that while equity market leverage is growing, it has not even come close to reaching a point where a correction leas to significant balance sheet stress.”

In other words, even if China’s markets crash, there may not be blood on the streets!

![submenu-img]() Ramesh Awasthi: Kanpur's 'Karma Yogi' - Know inspirational journey of 'common man' devoted for society

Ramesh Awasthi: Kanpur's 'Karma Yogi' - Know inspirational journey of 'common man' devoted for society![submenu-img]() Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'

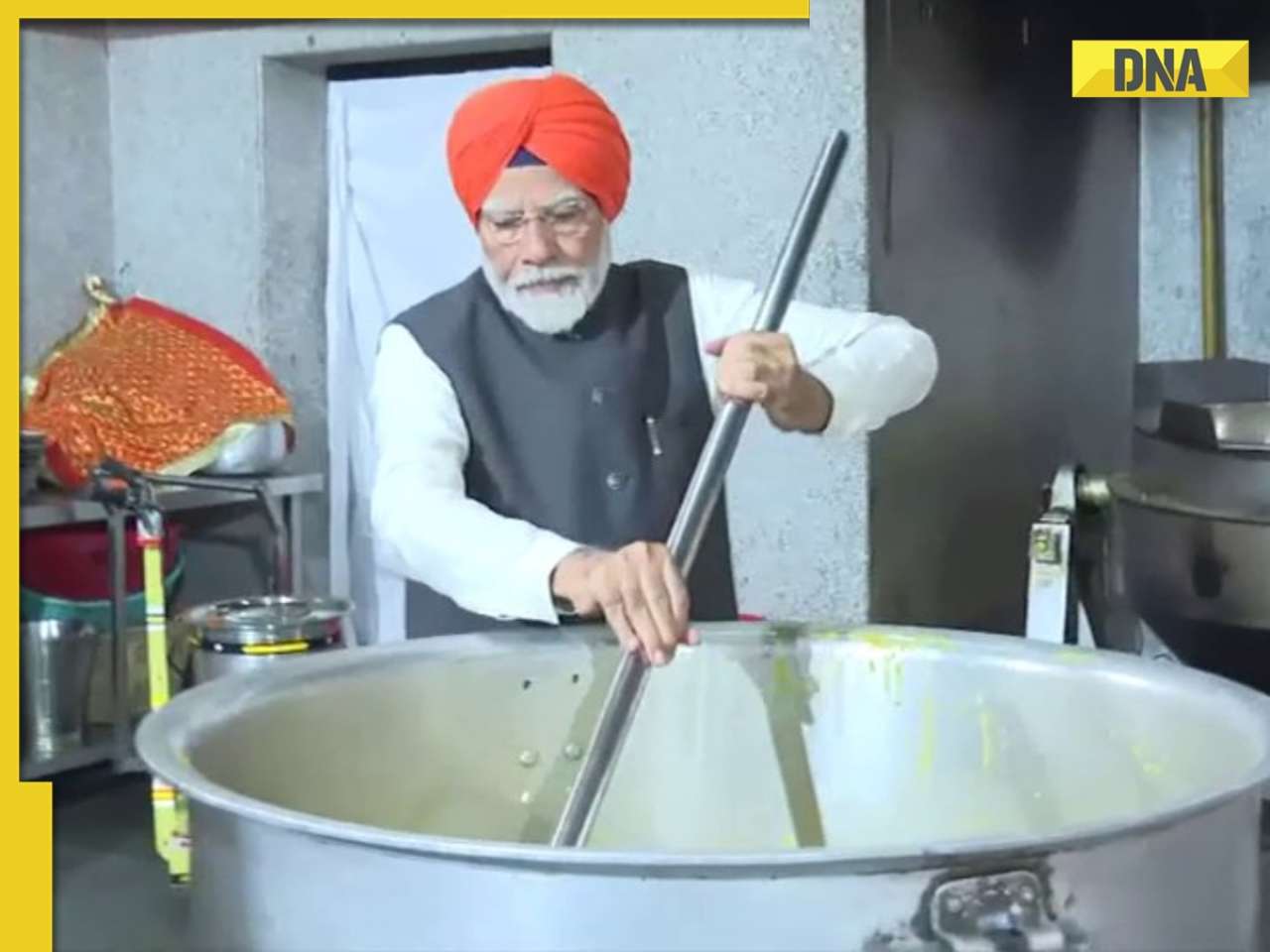

Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'![submenu-img]() PM Modi wears turban, serves langar at Gurudwara Patna Sahib in Bihar, watch

PM Modi wears turban, serves langar at Gurudwara Patna Sahib in Bihar, watch![submenu-img]() Anil Ambani’s debt-ridden Reliance’s ‘buyer’ now waits for RBI nod, wants Rs 80000000000…

Anil Ambani’s debt-ridden Reliance’s ‘buyer’ now waits for RBI nod, wants Rs 80000000000…![submenu-img]() Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious

Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious![submenu-img]() Maharashtra Board HSC, SSC Results 2024: MSBSHSE class 10, 12 results soon at mahresult.nic.in, latest update here

Maharashtra Board HSC, SSC Results 2024: MSBSHSE class 10, 12 results soon at mahresult.nic.in, latest update here![submenu-img]() Meet IIT-JEE topper who passed JEE Advanced with AIR 1, decided to drop out of IIT due to…

Meet IIT-JEE topper who passed JEE Advanced with AIR 1, decided to drop out of IIT due to…![submenu-img]() Meet IPS Idashisha Nongrang, who became Meghalaya's first woman DGP

Meet IPS Idashisha Nongrang, who became Meghalaya's first woman DGP![submenu-img]() CBSE Results 2024: CBSE Class 10, 12 results date awaited, check latest update here

CBSE Results 2024: CBSE Class 10, 12 results date awaited, check latest update here![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was denied admission in IIT due to blindness, inspiration behind Rajkummar Rao’s film, now owns...

Meet man, who was denied admission in IIT due to blindness, inspiration behind Rajkummar Rao’s film, now owns...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'

Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'![submenu-img]() Ratna Pathak Shah calls Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy's films 'offensive', says, 'women are constantly...'

Ratna Pathak Shah calls Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy's films 'offensive', says, 'women are constantly...'![submenu-img]() Shreyas Talpade recalls how he felt bad when his film Kaun Pravin Tambe did not release in theatres: 'It deserved...'

Shreyas Talpade recalls how he felt bad when his film Kaun Pravin Tambe did not release in theatres: 'It deserved...'![submenu-img]() Anup Soni slams his deepfake video from Crime Patrol, being used to promote IPL betting

Anup Soni slams his deepfake video from Crime Patrol, being used to promote IPL betting![submenu-img]() Real story that inspired Heeramandi: The tawaif who helped Gandhi fight British Raj, was raped, abused, died in...

Real story that inspired Heeramandi: The tawaif who helped Gandhi fight British Raj, was raped, abused, died in...![submenu-img]() Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious

Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious![submenu-img]() Lift collides with roof in Noida society after brakes fail, 3 injured

Lift collides with roof in Noida society after brakes fail, 3 injured![submenu-img]() Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal invites employees' moms to office for Mother's Day celebration, watch

Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal invites employees' moms to office for Mother's Day celebration, watch![submenu-img]() This clip of kind woman feeding rotis to stray cows will bring tears of joy to your eyes, watch

This clip of kind woman feeding rotis to stray cows will bring tears of joy to your eyes, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Seagull swallows squirrel whole in single go, internet is stunned

Viral video: Seagull swallows squirrel whole in single go, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)