Investors still think in herds and end up investing in stocks which are not fundamentally sound, just because others around them are doing so.

MUMBAI: “Each age has its peculiar folly, some scheme, project or phantasy into which it is plunged, spurred on either by the love of gain, the necessity of excitement, or the mere force of imitation… Money has often been a cause of the delusion of multitudes. Sober nations have all at once become desperate gamblers and risked almost their existence upon the turn of a piece of paper… Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly and one by one,” wrote Charles Mackay in Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, way back in 1852.

Things haven’t changed much since then. Investors still think in herds and end up investing in stocks which are not fundamentally sound, just because others around them are doing so. Why can’t we learn from the mistakes of our ancestors? Maggie Mahar, a financial journalist, offers us an answer in Bull! A History of the Boom and Bust, 1982-2004, a book on how the dotcom bubble in the United States was built and then went bust.

Every bubble has what seems like a new idea. The dotcom bubble in the United States worked on the belief that the so called “new economy” had made the old rules of investing outdated. So, even if a company was not making any money right now or probably would not make money for sometime to come, its shares still had to be bought, because in the long-term, the company would make huge profits.

This would be because these companies would see a productivity revolution, similar to the one brought in by the industrial revolution at the beginning of the twentieth century.

As Mahar writes, “Like everyone else, the pros and the pundits were caught up in the myth that the New Economy rendered the old rules of investing obsolete. Journalists could not help but catch the fever: many became true believers. Even Fed chairman Alan Greenspan cross-dressed as a cheerleader. True, in December of 1996, he spoke of “irrational exuberance,“ but a month later, when he spoke before the Senate budget committee, what was “irrational” had become “breathtaking”. Before long, Greenspan began to proclaim the wonders of a “productivity revolution not seen since early this century” as he made the case for rational exuberance.”

Every bull market that leads to a bubble finds its own set of buyers. So it happened in the US as well. Most of the investors had not seen a bear market. The US had been seeing a continuous bull run since 1982 (one or two hiccups not withstanding).

As Mahar writes “As for the old investors who suffered through the crash of 1973-74, by the time the next bull market began eight years later, the majority had retired from the field, so badly burned they would never touch a stock again. As a result, most of the investors, who buoyed the bull market of the nineties had never seen a bear. In 2002, fully 56 percent of those who owned stocks or stock funds had purchased their first shares sometime after 1990, while 30 percent of all equity investors had gotten their feet wet only after 1995”.

Stock market gurus, analysts and the media had their own roles to play in helping build the bubble. And they always did not give out the correct picture. As Mahar writes, “Often, their firms’ profits depended on the investment banking companies from the very same companies that they covered. No wonder, “sell” recommendations were rare.”

The research reports that the analysts write are distributed by the brokerage firm to institutional investors like mutual funds, insurance companies, foreign institutional investors and individual investors. And any analyst worth his salt would have been bothered usually about the institutional investors and not individual investors. This is because the level of respect of an analyst commands among institutional investors essentially decides what he earns.

Other than this, no brokerage firm ever makes money directly out of the report an analyst writes. Brokerage firms make money by getting investors to buy shares. As Mitch Zacks points out in his book Ahead of the Market, “A buy recommendation has more value to a brokerage firm because it gets the brokers on the phone selling stocks to new clients and opening new accounts.”

Analysts were left in what Mahar calls a Catch 22 situation. “If they recommended overvalued stocks, they were wrong, but if they downgraded those same stocks, they would also be wrong - at least for as long as the market continued to rise.”

And the media left no stone unturned in taking the opinion of the analysts (very little of it was analysis anyways) to the mass market. Brokerage houses made “morning calls,” which were basically buy recommendations on various stocks.

As Mahar writes, “Indeed, if 10,000 brokers are telling their clients something while the tip is simultaneously broadcast on CNBC - all before the market opens - the morning

call is likely to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The media projected stock market investing as something which involved minute-to-minute decision-making. As Mahar points out, “The perennial problem for the media is that balance sheets do not fluctuate on a daily basis. Once a reporter has laid out a company’s assets and debts, how does he fill the news hole the next day? Only by tracking market’s daily performance.”

But tracking the markets on a real time basis only brings in information. But, is this the information investors really need. As Mahar writes “The problem is that much of the information that investors want - and think they need - is just that, “information,” not knowledge. Knowledge comes only through time. It dawns on us gradually, as we digest bits of information, reflect on them, and rearrange them, revising and refining out interpretation. But the new age of information aimed to collapse time. An investor no longer had to wait for tomorrow’s newspapers to hear the news: the future was now.”

Due to all these reasons, the bubble kept growing, until it finally burst and left many investors on the wrong side of it. And all this happened because, during such times, the normal law of demand fails to work.

As Mahar writes “In the normal course of things, higher prices dampen desire. When the lamb becomes too dear, consumers eat chicken; when the price of gasoline soars, people take fewer vacations. Conversely, lower prices usually whet our interest: color TVs, VCRs, and cell phones become more popular as they become more affordable. But when the stock market soars, investors do not behave like consumers. Rather, they are consumed by stocks.

Equities seem to appeal to the perversity of human desire. The more costly the prize, the greater the allure. So, at the height of the bull market, investors lust after the market’s leaders. (Conversely, when the prize is too ready at hand, investors lose interest. At the bottom of the bear market, when equities are bargains, they go begging, like overly earnest, suitable suitors.)”

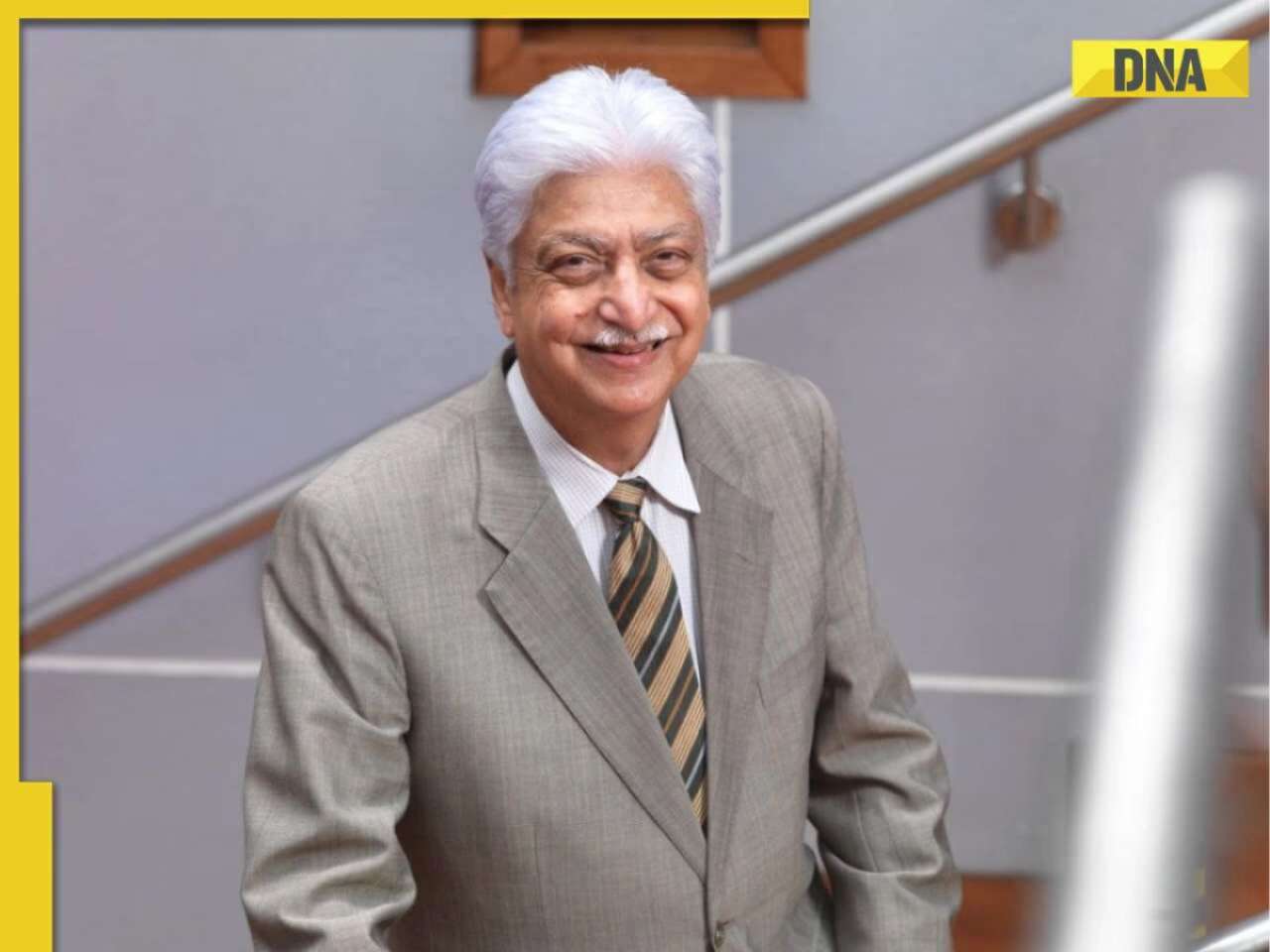

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

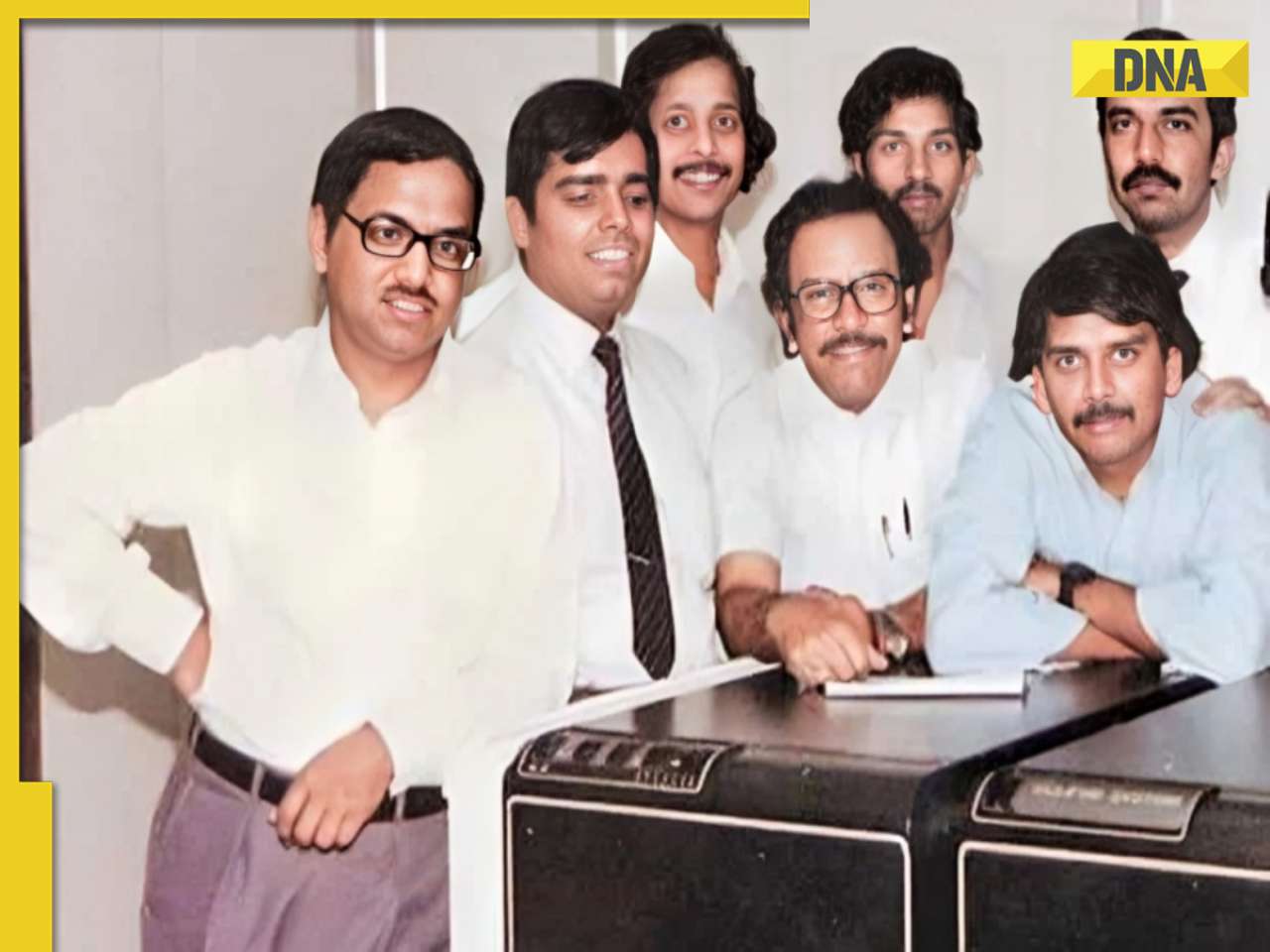

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)