Cars are the new kids. And children are losing their play spaces to parking lots. Sanghamitra Bhowmik reports.

It is five in the evening. The homework is all complete and 12-year-old Umang Chitle and his friends take the lift to the ground floor and look for a free parking lot to start their daily game of lagori.

The game is in full swing when a car zooms in and parks in its designated parking space — Umang and his friends' playground for this evening.

With the average middle-class family owning two or more cars, the shortage of parking space has never been so acute. And the first to feel the brunt are children, who are fast losing their playgrounds and every available inch in the building compound.

With 13.5 lakh vehicles plying on city roads daily and 200 new cars entering Mumbai roads everyday, the city is hard pressed for parking space.

With every new building project that comes up, urban planners and builders involved have to think about accommodating the growing number of cars. What is being sacrificed in the process are children's play spaces.

First to go were the streets and lanes of yesteryears where earlier generations used to play with great abandon. Soon the pavements vanished too once parking was permitted on them. Now some of the new apartment blocks are foregoing play spaces to accommodate parking spaces for cars.

“I feel sad that Umang has no open ground to play in. He and his friends make do with whatever free space there is in the building,” says his father Pranab Chitle.

Born and brought up in Malad, Chitle claims this wasn't the case when he was growing up. As the fastest growing western suburb in the city, Malad sported a very different landscape five years back with mangroves, coconut trees and open spaces.

Today, major roads, streets and even narrow by-lanes have been converted into parking lots.

Old city area like Matunga, Dadar, Mahim, Napeasea Road, Walkeshwar that sport traditional 4-5 storey buildings too are fast filing up all available space with cars.

“Most people here park their cars on the roads, making the roads inaccessible for children to play in. Of course, compared to the suburbs, Matunga has more gardens and parks. Nevertheless, when you put into perspective the situation during the days my children grew up, now, the number of cars have increased and roads are unsafe,” says Rashmi Kidwai, a housewife from Matunga.

The shortage of open spaces in Mumbai's skyline has never been so obvious. The Bombay High Court in its judgment on developing mill lands mentions the need to set aside open spaces.

According to a study conducted in 1970, Mumbai has 0.03 acres (or less) of open space per 1,000 people. This is approximately 6 per cent of the required space, which is 0.5 acres per 1,000 people.

Experts believe that the ratio is 0.015 acres per 1,000 persons today — approximately 540 times lesser than the requisite minimum.

“Mumbai has the worst open space-people ratio. We rank the lowest in the country,” says Prasad Shetty of Collective Research Initiatives Trust (CRIT), an organisation, which researches urban spaces.

“It isn’t just lack of open spaces but the lack of safe spaces that’s worrisome. Pavements, public parks and streets, which were safe earlier, are now taken over by hawkers, encroachers making them unsafe for children.”

“In the mad rush to build homes, most builders overlook the basic need for open spaces. While bigger builders catering to the upper class offer playgrounds, club houses and other recreational facilities to their residents, those building homes for lower and middle income groups often miss the vital open space required for children,” says Shetty.

With no laws to govern open space requirements in building societies, builders prefer using all available land for construction.

“There is no hard and fast rule regarding open spaces in building societies. It depends on the size of the plot, height of the building and size of the project. Smaller plots however, don't necessarily need to set aside an open space or playground,” says VD Ingwale, executive engineer, building proposal department (Eastern suburbs), BMC.

The entire system — from housing to schooling — seems to revolve around concrete and glass. Even schools don't have playgrounds anymore. Small wonder then that kids watch more of adult television.

Umang and his friends, meanwhile lose out on their patch of open sky and greens — they haven't played in a real playground, ever.

“It must be fun, but we don't have any playground in the building or in the neighbourhood,” says Umang as he runs off with his friends to play hide-n-seek among the parked cars.

![submenu-img]() Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...

Big update on Pakistan's first-ever Moon mission and it has this China connection...![submenu-img]() 2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…

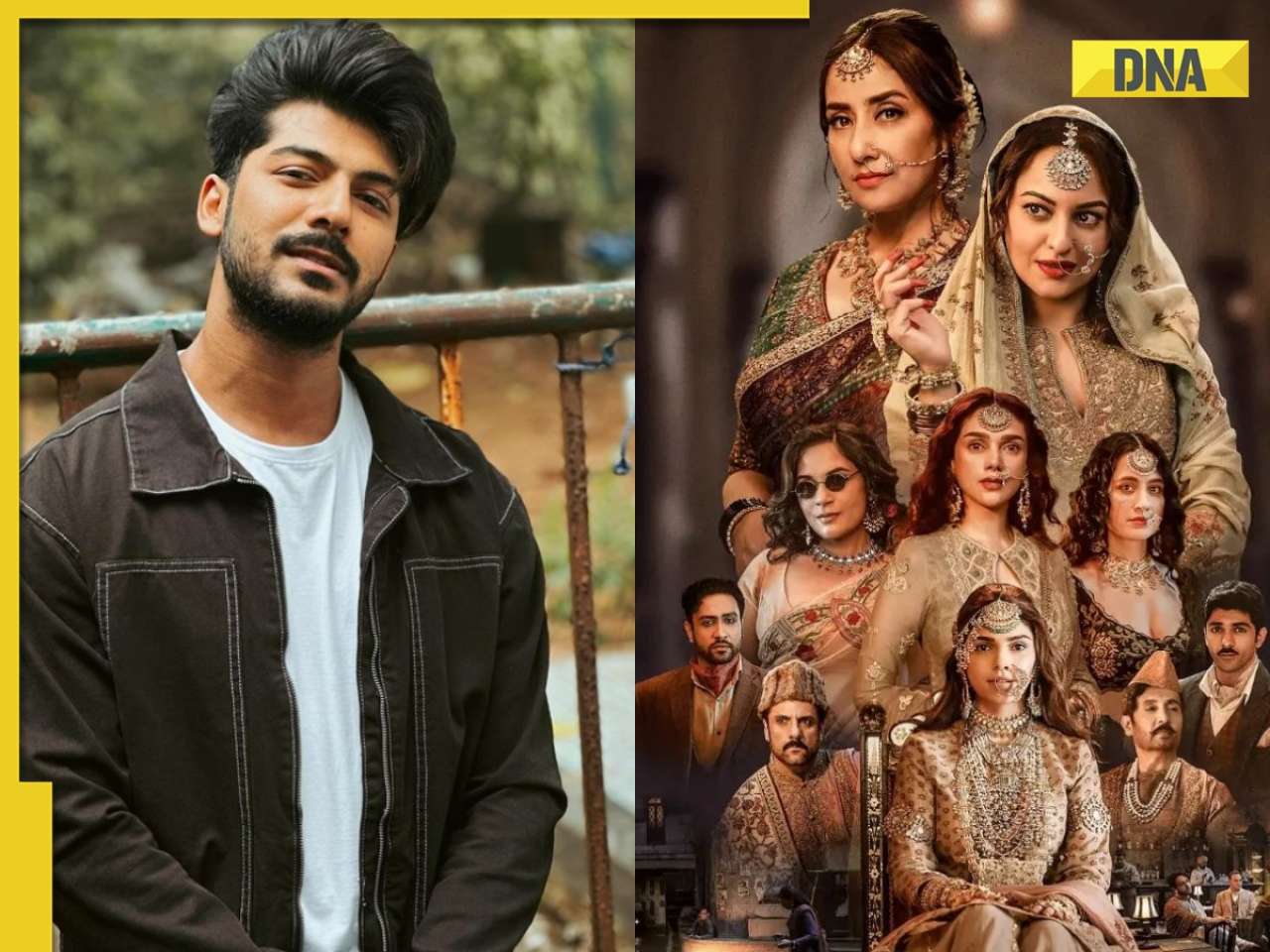

2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…

Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…![submenu-img]() Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police

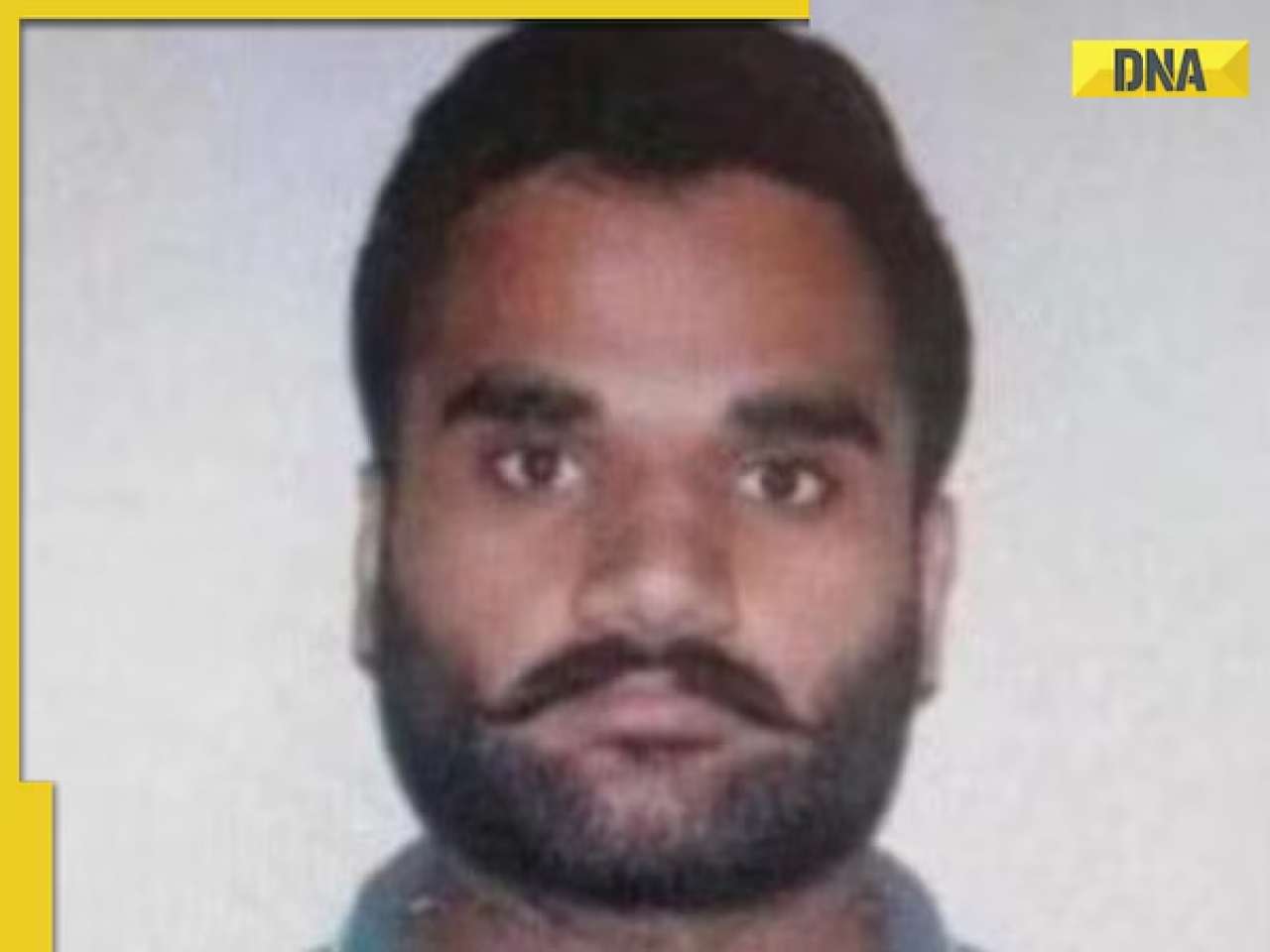

Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..

Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’

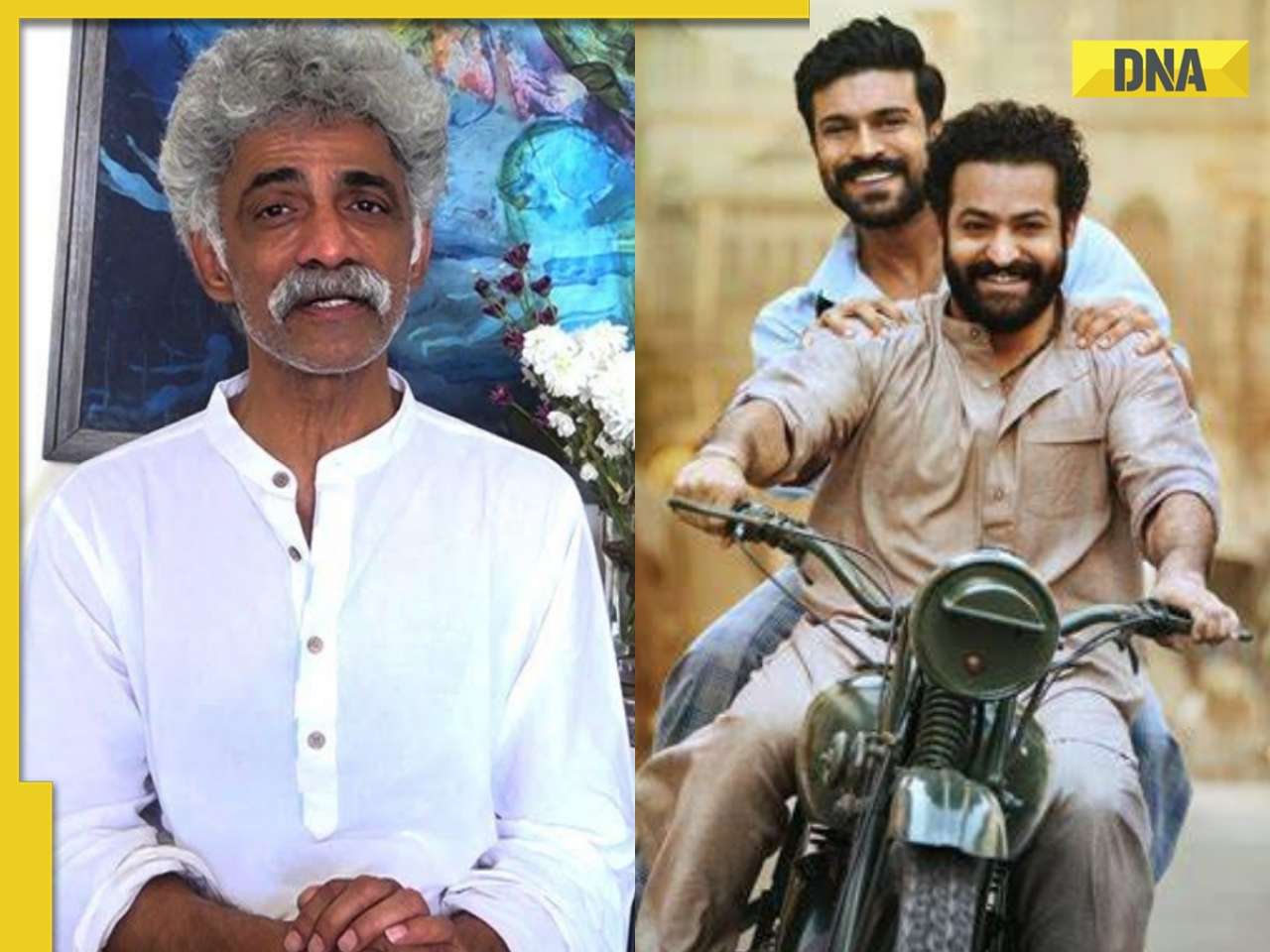

Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’![submenu-img]() Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...

Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...![submenu-img]() Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore

Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets

IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets![submenu-img]() Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here

Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals

SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch

Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch

Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts

Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet

Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet![submenu-img]() Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)