From all across China, people gather daily in Tiananmen Square to pay homage to China’s most famous revolutionary leader.

BEIJING: From all across China, they gather daily in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square: thousands shuffling their way to a majestic monument at one end of the alfresco Square.

All around are throngs of people, their voices raised in excitement, but the mood among those queued up is rather more solemn.

Their mission: to pay homage to China’s most famous modern revolutionary leader, Mao Zedong, whose 30th death anniversary falls on September 9. These are the silent admirers of the Great Helmsman (as he was known), his own private army of adherents.

In a day and age when China has moved far away from Mao’s socialist ideology, when unabashed materialism rules the day, and when Mao’s own place in Chinese history is gradually being consigned to footnotes, those gathering at his mausoleum, where his body lies in state, in a crystal coffin, are living, breathing testimony to the fact that in death, as in life, Mao has the capacity to move millions of his countrymen.

China’s official media will likely play down this anniversary, as it has those of recent years.

That’s because Mao’s legacy is something of a mixed blessing for China’s leaders. Despite his image, in the official propagandist line at least, as the man who “liberated” China, defeated the Japanese and united the country, Mao also unleashed unspeakable horrors on his own people

Millions of people died during the Great Leap Forward, an ill-conceived programme of rapid industrialisation that led to famines in the late 1950s, and then the Cultural Revolution, the anarchic decade from 1966 when Chinese society was rent asunder by Mao’s machinations.

Today, the official assessment of Mao’s legacy takes on a formulaic characterisation: he was 70% right, 30% wrong.

Those numbers are playing on my mind as I find myself in Tiananmen Square one morning, heading for the tail-end of the queue outside of his mausoleum. All around me are peasants from Anhui, factory workers from Hubei, and migrant workers from Hunan (where Mao was born in 1893), their rugged but pacific faces do not refelct any discomfort despite the heat of the day.

The queue is miles long and there’s a 30% chance that I may not gain entry by mid-day, when the mausoleum closes. It’s my last day in Beijing, and I am perhaps more than a little desperate.

Soon enough, a “solution with Chinese characteristics” presents itself. A man sidles up, and helps me jump the queue – or should I say, make the Great Leap Forward – for a small consideration.

A hush falls over the crowd as we troop into the mausoleum. In the centre of the main hall lies the embalmed body of the man who rose from humble origins to preside over the destiny of millionse. Even in death, Mao’s image is carefully managed.

Xenon lamps inside the coffin provide illumination that ensures that the pallor of his skin is “life-like”, and even “irons out” his wrinkles. In those fleeting moments, during which we file past his coffin, I can’t help but wonder at the amazing likeness Mao’s cadaver bears to his waxen image at the museum nearby.

It is only the emotion among ordinary people that serves to keep Mao’s memory alive, long after the Communist Party and its leaders have, in practice at least, forsaken his thoughts.

![submenu-img]() Ramesh Awasthi: Kanpur's 'Karma Yogi' - Know inspirational journey of 'common man' devoted for society

Ramesh Awasthi: Kanpur's 'Karma Yogi' - Know inspirational journey of 'common man' devoted for society![submenu-img]() Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'

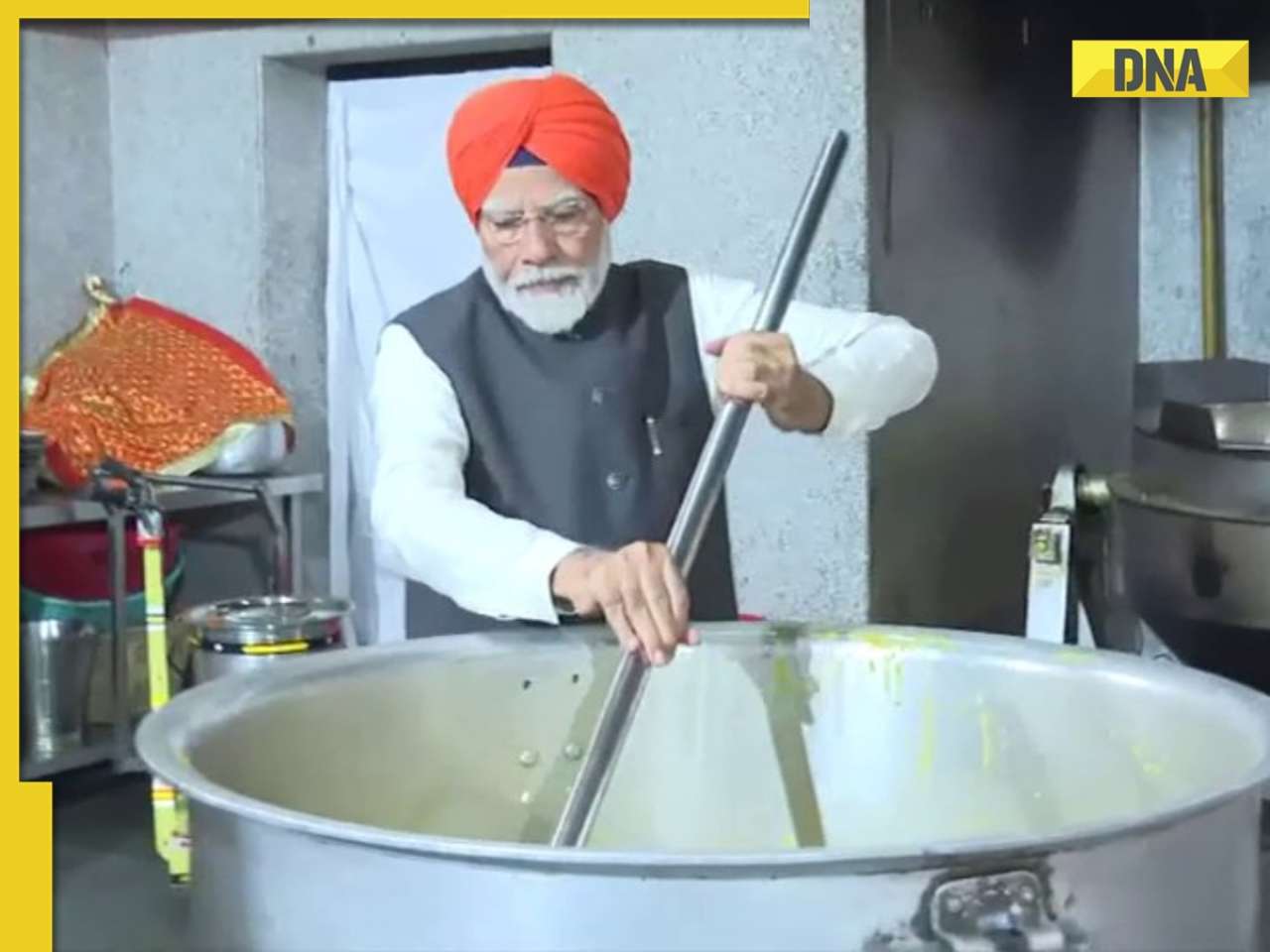

Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'![submenu-img]() PM Modi wears turban, serves langar at Gurudwara Patna Sahib in Bihar, watch

PM Modi wears turban, serves langar at Gurudwara Patna Sahib in Bihar, watch![submenu-img]() Anil Ambani’s debt-ridden Reliance’s ‘buyer’ now waits for RBI nod, wants Rs 80000000000…

Anil Ambani’s debt-ridden Reliance’s ‘buyer’ now waits for RBI nod, wants Rs 80000000000…![submenu-img]() Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious

Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious![submenu-img]() Maharashtra Board HSC, SSC Results 2024: MSBSHSE class 10, 12 results soon at mahresult.nic.in, latest update here

Maharashtra Board HSC, SSC Results 2024: MSBSHSE class 10, 12 results soon at mahresult.nic.in, latest update here![submenu-img]() Meet IIT-JEE topper who passed JEE Advanced with AIR 1, decided to drop out of IIT due to…

Meet IIT-JEE topper who passed JEE Advanced with AIR 1, decided to drop out of IIT due to…![submenu-img]() Meet IPS Idashisha Nongrang, who became Meghalaya's first woman DGP

Meet IPS Idashisha Nongrang, who became Meghalaya's first woman DGP![submenu-img]() CBSE Results 2024: CBSE Class 10, 12 results date awaited, check latest update here

CBSE Results 2024: CBSE Class 10, 12 results date awaited, check latest update here![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was denied admission in IIT due to blindness, inspiration behind Rajkummar Rao’s film, now owns...

Meet man, who was denied admission in IIT due to blindness, inspiration behind Rajkummar Rao’s film, now owns...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'

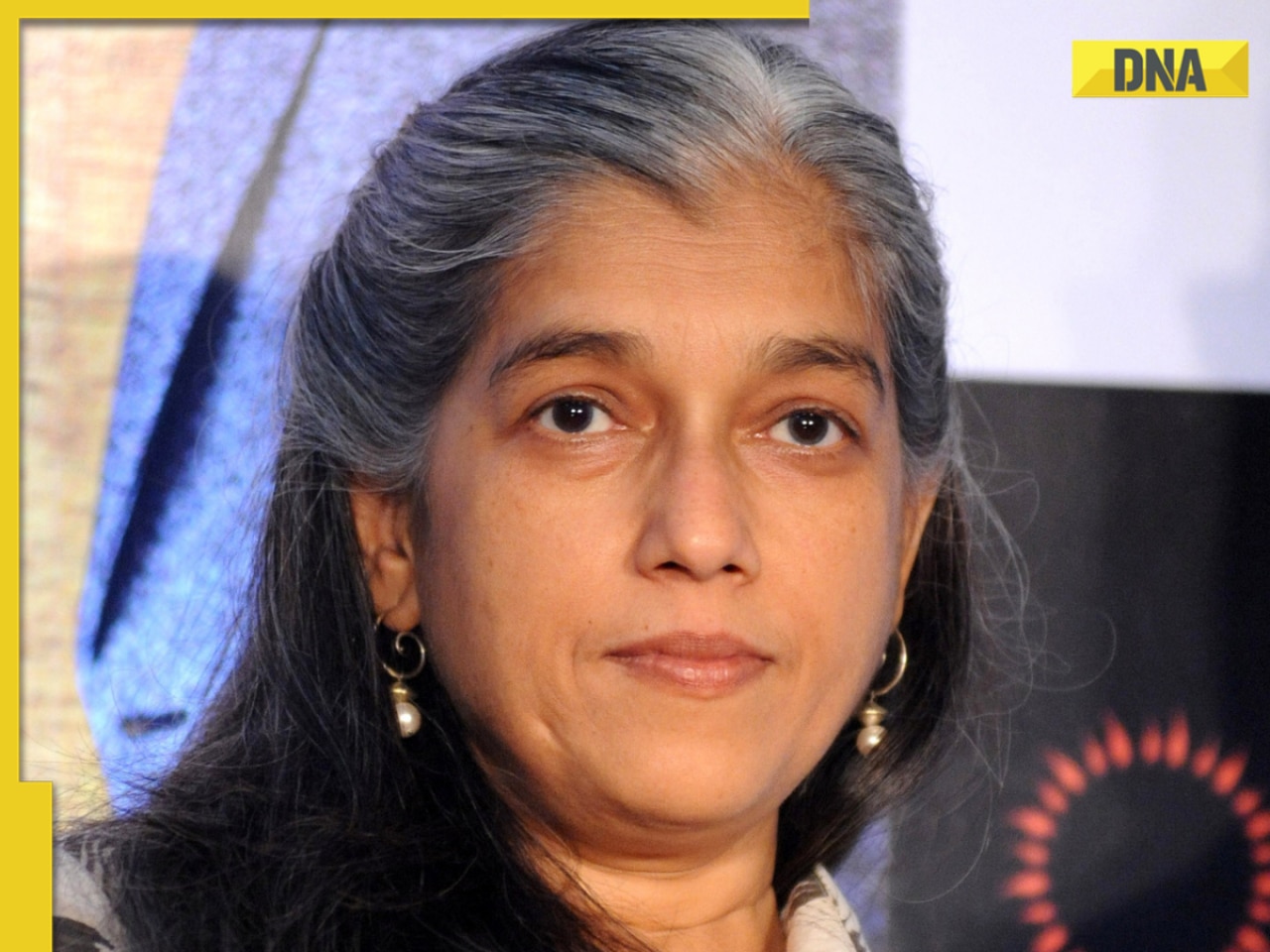

Tovino Thomas accused of stopping his film Vazhakku's release by director Sanal Kumar Sasidharan: 'The agenda of...'![submenu-img]() Ratna Pathak Shah calls Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy's films 'offensive', says, 'women are constantly...'

Ratna Pathak Shah calls Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy's films 'offensive', says, 'women are constantly...'![submenu-img]() Shreyas Talpade recalls how he felt bad when his film Kaun Pravin Tambe did not release in theatres: 'It deserved...'

Shreyas Talpade recalls how he felt bad when his film Kaun Pravin Tambe did not release in theatres: 'It deserved...'![submenu-img]() Anup Soni slams his deepfake video from Crime Patrol, being used to promote IPL betting

Anup Soni slams his deepfake video from Crime Patrol, being used to promote IPL betting![submenu-img]() Real story that inspired Heeramandi: The tawaif who helped Gandhi fight British Raj, was raped, abused, died in...

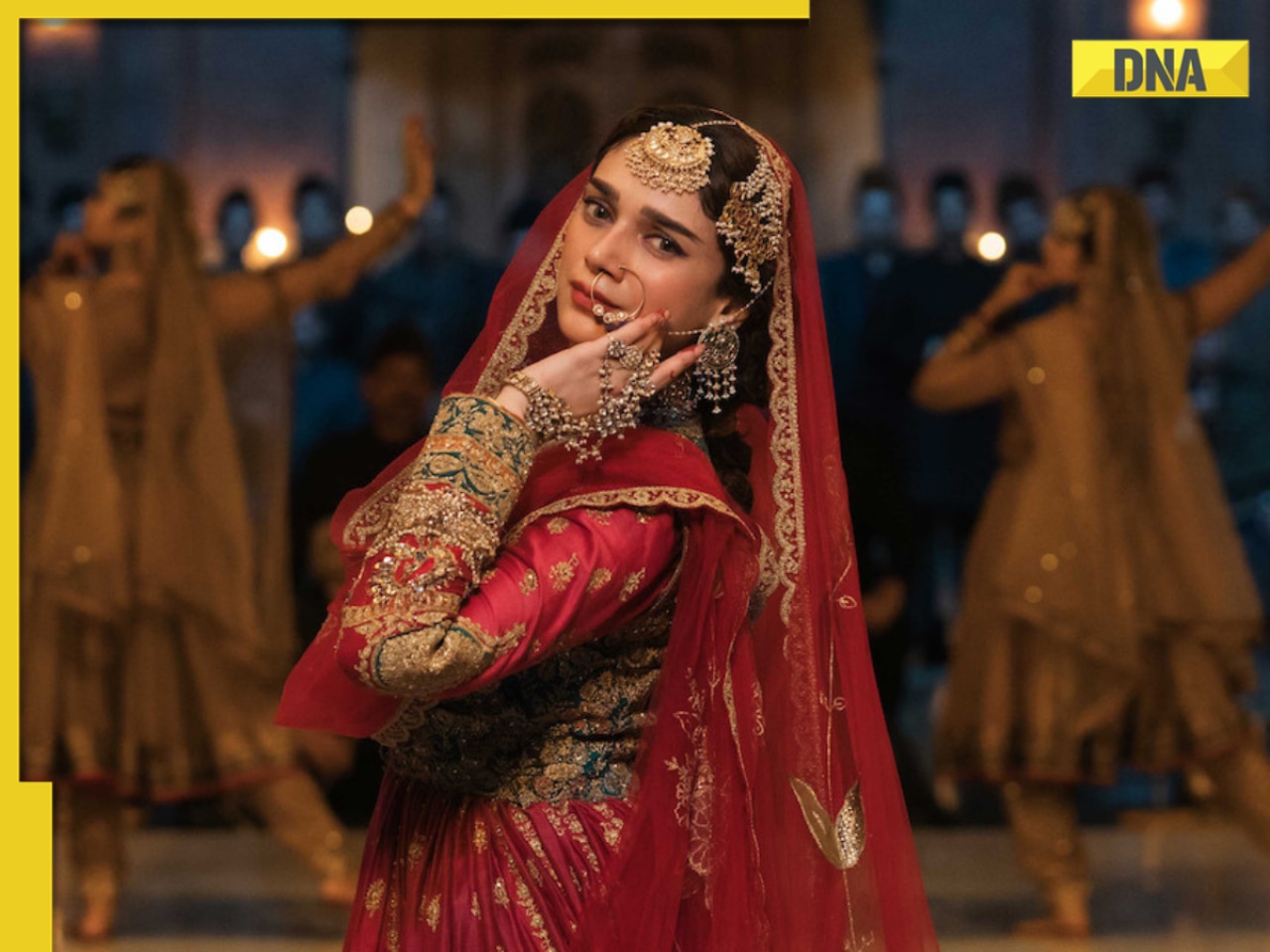

Real story that inspired Heeramandi: The tawaif who helped Gandhi fight British Raj, was raped, abused, died in...![submenu-img]() Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious

Man in bizarre jeans dances to Tinku Jiya in crowded metro, viral video makes internet furious![submenu-img]() Lift collides with roof in Noida society after brakes fail, 3 injured

Lift collides with roof in Noida society after brakes fail, 3 injured![submenu-img]() Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal invites employees' moms to office for Mother's Day celebration, watch

Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal invites employees' moms to office for Mother's Day celebration, watch![submenu-img]() This clip of kind woman feeding rotis to stray cows will bring tears of joy to your eyes, watch

This clip of kind woman feeding rotis to stray cows will bring tears of joy to your eyes, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Seagull swallows squirrel whole in single go, internet is stunned

Viral video: Seagull swallows squirrel whole in single go, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)