As Mumbai gets going on its project, a determinant of its success will be its ability to induce users of private transport.

Lessons from efficient mass transit systems around the world

HONG KONG: In the garage of Sunil Joshi’s home in Tsing Yi, a neighbourhood in Hong Kong, is parked a stately sedan. Yet, for his daily commute to and from his office in a glass tower in the financial district of Central, he takes the MTR, Hong Kong’s famed metro railway system that streaks beneath this world city at top speed, bearing 2.4 million passengers every day.

“The car is for family outings,” says Joshi. “Only a sense of vanity could compel me to drive to work and pay exorbitant parking charges when there’s the MTR, which is among the most efficient, the most comfortable and the cheapest urban transport systems in the world.”

As Mumbai gets going on an ambitious Metro project, a critical determinant of its eventual success in decongesting the metropolis’ roads will be its ability to induce users of private transport - like Joshi in Hong Kong - to get out of their cars and migrate to the Metro, says an urban transportation policy expert who has studied 15 metro systems around the world.

Dr Priyanka Jain, Instructor in the Public and Social Administration Department at the City University of Hong Kong, emphasises that Mumbai’s Metro should, in fact, be targeted not at people who are already using public transport facilities, but at “people like us”, who drive to work and back in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

And drawing from her study of metro systems around the world - from Tokyo to Santiago - Jain recommends that such a middle-class migration to the Metro can be encouraged through a system of “area licensing” that efficient metropolitan administrations in some world cities have implemented.

“The central business district, which is typically the most congested area with the most number of office complexes, could be cordoned off, and anyone entering the area in a private vehicle must pay a toll.”

Additionally, as in Hong Kong, a “fuel tax” could serve as a disincentive to use private vehicles, she adds. These could prove politically unpopular, concedes Jain, but they are the building blocks for delivering efficient mass transit systems as in Tokyo, Hong Kong or Singapore.

Another critical factor that will impact the Mumbai Metro’s efficiency is the extent to which existing public transport facilities — like the suburban electric train system and the bus services — are integrated with the Metro. “Rather than compete, the planning should be done in such a way that they integrate: the suburban railways feed passengers to the metro system, which carries them within the Mumbai core area.”

Equally important, she says, is for the project planning to provide for expanded service operations in the future. She reckons that having a train service with just 4-6 cars and a headway of 4-6 minutes, as envisaged in the Mumbai Metro, will be grossly insufficient for a city with a 20 million population. Indicatively, in Hong Kong, which has a population of just 7 million, the MTR runs 12-car services with a headway of 60-90 seconds.

“Unless you plan for these now - in terms of platform length and signalling systems - the system will not be scaleable,” notes Jain.

Emphasising the importance of ensuring that the Metro remain self-financing and self-sustaining - without governmental subsidy - Jain suggests a course of action that has proved eminently success in other cities: the vertical separation of development. “This is an arrangement where the government provides the basic infrastructure: the railway stations, platforms, tracks, signalling… the works. But the operation is then privatised; a company can get in its own rolling stock - like train cars - and its own staff and operate it on day-to-day basis.” Under such an arrangement, the government can recover its costs by reaping the benefit of increased property values along the railway lines. And the firm that’s operating the rail system can recover its costs from the fares, without its being subsidised by the government.

In Hong Kong, the system works a little differently: the MTR Corporation uses its own finances to develop the railways, including construction of the system, and to operate it. But the government gives the corporation premium land, where it can build houses and shopping complexes in and around the station concourse, and collect a rent. In fact, the MTR’s profits on its property holdings are substantially higher than on its railway operations.

The bottomline, according to Jain, is that the Metro should be run like a business, with an eye on profits from efficiency of operations. Only that, she says, will get the Metro on the right track.

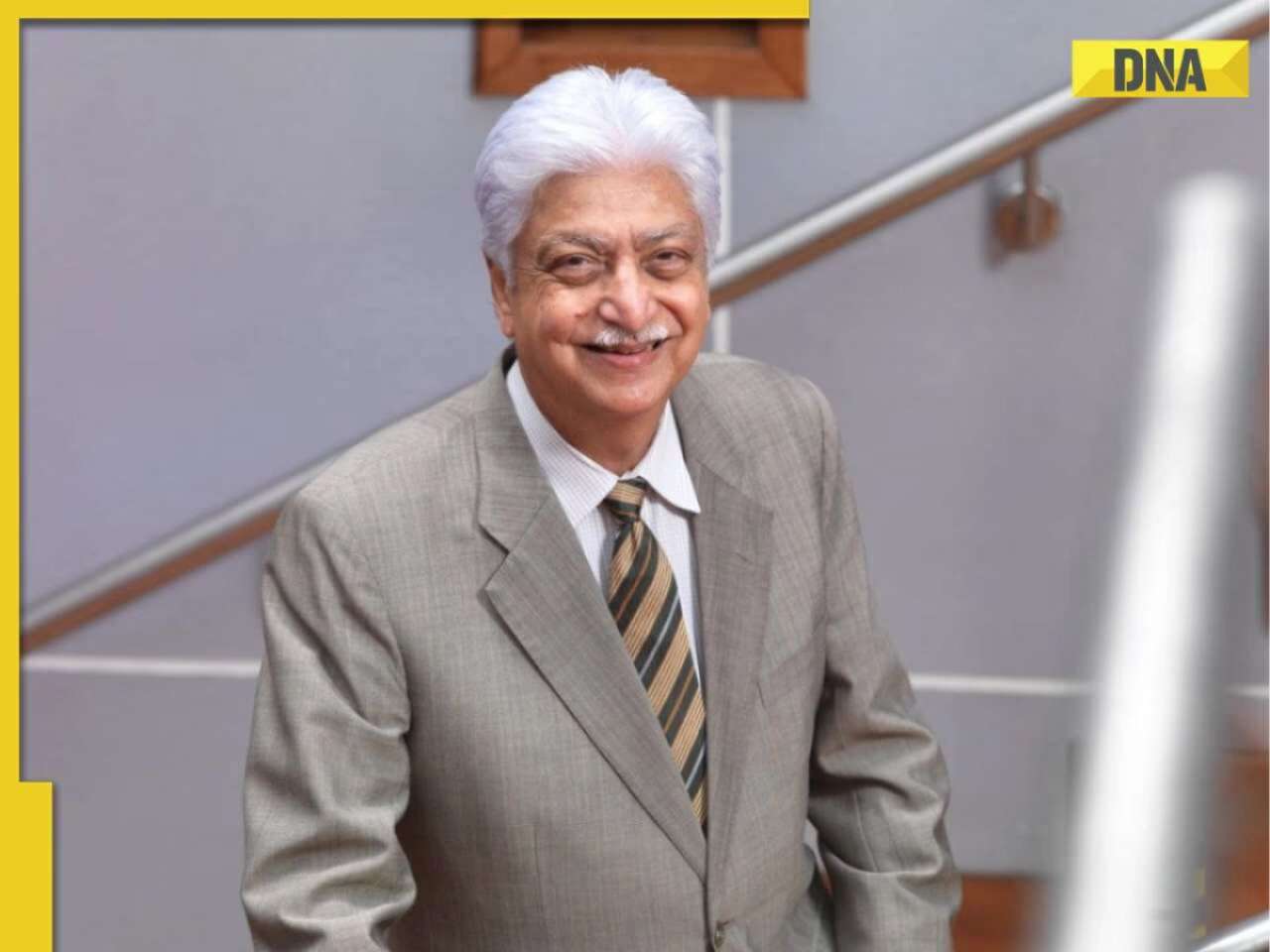

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)