Jaanvi Phuphaney rubs her rheumy eyes with gnarled fingers.

Tears well up as the trembling 75-year-old Warli tribal struggles to ease her emaciated body out of her hut in Ghivanda-Pimpalpada, 14km from the Jawhar tehsil town in Thane district. “My husband Sohni and I have not eaten in two days,” she says with folded hands.

Both her daughters are settled in neighbouring Mokhada tehsil.

But son Pandu, 38, lives barely a stone’s throw away with his wife, Muli, 32 and daughter Poonam, 9.

“When he can afford it, he feeds us. Other times he has to think of his family,” says Sohni, 78.

Pandu says the nearly Rs5,000 per year he earns as a labourer on a sand-dredging boat is hardly enough to make ends meet for himself. “We are landless. I grow some paddy on an encroached forest plot but that and my earnings hardly suffice. We ourselves go hungry so often,” he says.

Jaanvi and Sohni are not alone. At least 29 of the 82 families in the village have built separate huts for the elderly, many of who are undernourished. A better part of these huts is barely tall enough for a person to stand.

Kamlibai Phuphaney, 68, is all skin and bones. Diagnosed with protein-energy malnutrition and weighing 27kg, she was taken to the rural hospital at Jawhar, 20km away, on a motorcycle. “I felt my end is near. I came back because I wanted to be with my own people,” she says, gasping for breath.

Nearly 14 km across the valley in Winwal village, Harbya Bhore, 85, stares vacantly. Villagers say he’s been in shock since his wife Devaki collapsed from hunger and died in front of his eyes a year ago. “I couldn’t afford to keep them with me and built them this hut for their stay. I’d feed them whenever I could,” says Harbya’s son, Yash, 65.

Ironically, a year since his mother’s death, Yash’s son and daughter-in-law threw him and his wife, Siti, out of the house. “We live with my father. We work on farms when we get work,” he says.

His BPL ration card helps him buy foodgrains at a cheaper price.

His neighbour Dhavalibai Sutar, 70, is not as lucky. Her daughter died of malnutrition when she was barely two, her son of sickness when he was nine. She lost her husband last year. “He used to keep vomiting bile. I could only lay him down and watch him die.”

She got her small home dismantled and sold off the wood to raise money for her husband’s last rites. “All I could then do was build this,” she says, pointing to the small hut in which she has to crawl in. She walks for over three hours through the forest to Jawhar town to beg at the Thursday weekly market. “I have no BPL ration card and I’m forced to buy expensive grains with whatever money people give me.”

The two schemes Indira Gandhi Old Age Pension Plan and the Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Anudan Yojana (destitute beneficiary will get Rs600 a month and family with more than one beneficiary will get Rs900 a month) supposed to take care of exactly this demographic don’t seem to have reached here.

Jaanvi and Kamlibai have little more than pass-books to show for the pension scheme. “They expect me to go to Jawhar and queue up for the money. How can I do that in my condition?” asks Jaanvi.

As for Kamlibai whose hair is still jet black, the doctors at Jawhar kept certifying her as 55 for three years till she was helped by activists to get a pension started two years ago. Till last year, it came irregularly and, now, has stopped.

Ashok Shingare, the Jawhar addition collector, says he’s unaware of the issue. “I will ask the local tehsildar to inquire and see what we can do.” He, however, insists: “The tribals’ illiteracy and backwardness is equally to blame for the situation.”

Shiraz Balsara of the adivasi advocacy group Kashtakari Sanghatna says the vicious cycle the tribals find themselves in is a result of the government’s faulty approach. “The elderly who die of hunger are passed off as age- or sickness-related. Unless the district administration makes an effort to revitalise the schemes, the deaths and their acceptance will continue to be seen as normal.”

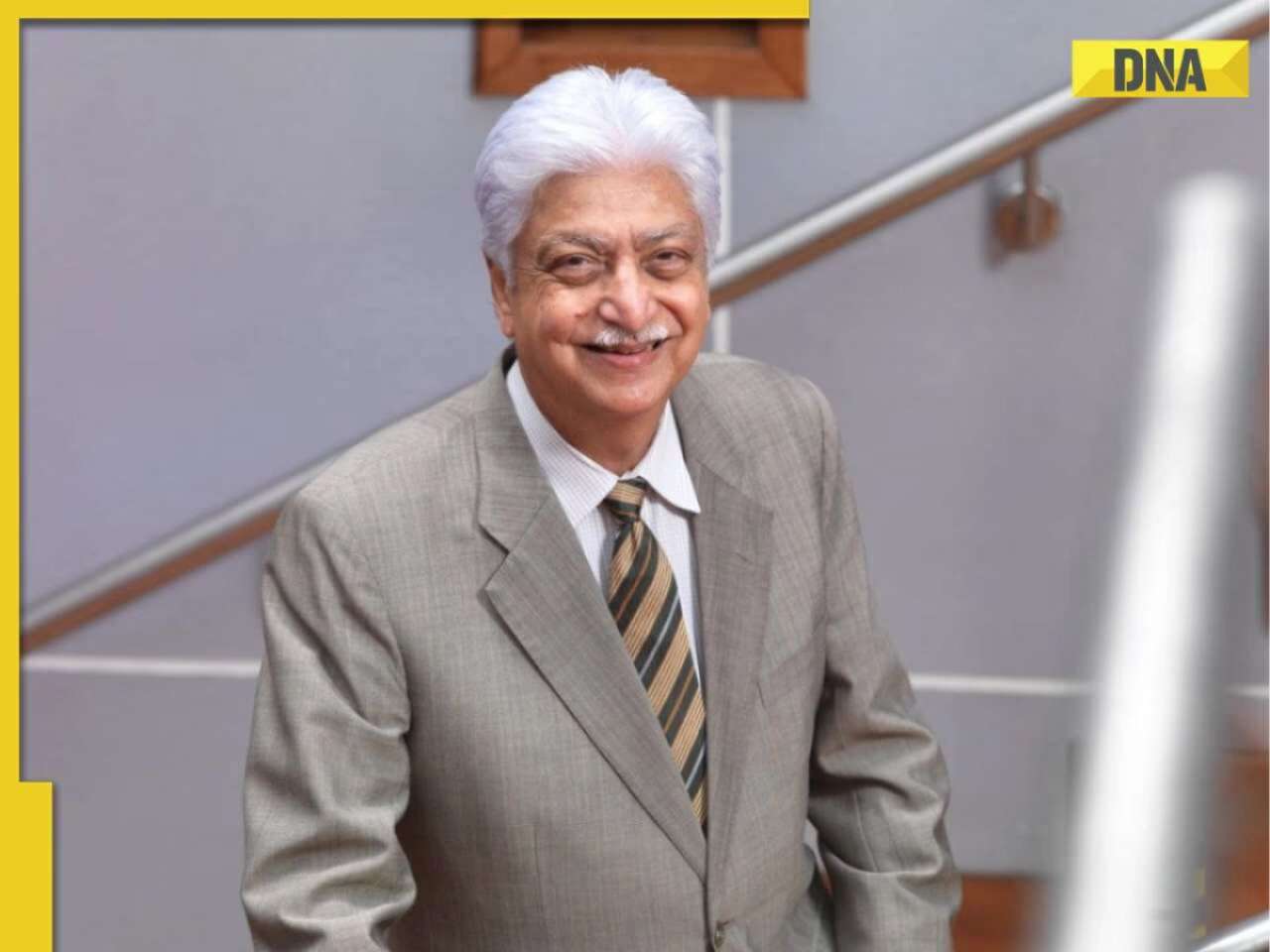

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)

)