It may be referred to as a ‘toy train’, but for the people of Darjeeling whose lives revolve around it, it is anything but, finds Lhendup G Bhutia, who spoke to the director of the award-winning documentary The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway.

It may be referred to as a ‘toy train’, but for the people of Darjeeling whose lives revolve around it, it is anything but, finds Lhendup G Bhutia, who spoke to the director of the award-winning documentary The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway.

As children, it was difficult for us to hitch a ride from Ghoom to Darjeeling. We’d stroll and trudge, hoping for a car to come by. And then, on those cold foggy mornings, it would appear out of nowhere. At first only its nose visible, and then its body as it twisted around the hilly bends like a caterpillar. The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (DHR) train chugged with an urgent ferocity that was amusing, because it was a toy train and so very slow.

We would jump on to it; the tourists didn’t mind, and neither did the staff. And we’d be off before the ticket inspector at Darjeeling station came to check for tickets. In case we needed to visit the bathroom, we would hop off, take a leak and jump right back in.

However, once we grew up, we would joke about the train. “Why travel nine hours, from Siliguri to Darjeeling, when one can make the journey in less than three hours, in a car?” But every time we travelled to Darjeeling, we were powerless to resist it. Its whistle would make our cars stop, while it crossed the road. At that moment, no matter how many times we may have seen the train, we became children again. And we would stare at it, wide-eyed.

In many ways, the newly released documentary, The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway by Shillong-based filmmaker Tarun Bhartiya (39) is a story about the people of Darjeeling and the close relationship they have shared with the train since 1881. The film, which won the UK’s coveted Royal Television Society Award (Best Factual Series) this year, peeks into their lives.

Thus, there is 43-year-old widow Sita Chettri, a mother of five, who works as a porter in the DHR and wants to educate her sons; Nima Yolmo, who is not only the strict ticket inspector at Darjeeling station, but also a monk; Hari Chettri, 43, (no relation of Sita’s), the proud assistant driver of the DHR steam engine trains, who doesn’t think highly of diesel engine drivers; and Pemba lama, whose job is to walk from station to station spraying ‘grass killers’.

But the narrow gauge train on the two-feet-wide track, as the documentary shows, is more than just a train. It is a source of sustenance to a community that revolves around it. It is a 52-mile-long adventure playground, where children, after finishing home work, slide down the long curving tracks on cartwheels.

And it is a noisy old neighbour you turn to for small favours. For instance, households that are too poor to afford geysers wait at train stops to use the hot water from the train for their baths.

The woman porter

Despite the documentary having been shown on TV only in the UK, a local channel in Darjeeling got hold of a copy and telecast it. As a result, the characters featured in it are now dealing with new-found fame.

College student Kedar Chettri (19), one of Sita Chettri’s sons, says, “Complete strangers are now coming up and congratulating me. Some even applaud what my mother is doing.” Two of Sita’s sons are in college, while the other three are in school. The family of six lives in a one-room house and joins the two beds every night to sleep together. She earns Rs200 on a good day. She is not clear how she’ll pay for the education of all her sons, but till date she hasn’t allowed any of her sons to skip studies and work.

The monk who’s a TT

In the documentary, 54-year-old Nima Yolmo’s mother sits hunched beside him as he’s interviewed, disappointment etched on her lined face. She is horrified to hear that he’s planning to apply for voluntary retirement and leave her to live in a monastery.

“You are not thinking of my grief,” she tells him.

Yolmo’s mother died a few months ago, before the documentary was ready. Yolmo now hopes to get his retirement approved by 2011, so he can leave home. “I always wanted to quit worldly ties and dedicate myself to religion, but couldn’t because my family required money.”

Using paper to stop an engine leak

Hari Chettri has driven trucks and diesel-engine trains, but says they are nothing compared to a steam-engine train. “The DHR has to carry the load of three compartments to up to 7,407 feet. One has to manually break the coal and feed it to the train. A little bit of mismanagement and the train can come to a halt. On diesel engines, you flick a switch and brakes take effect immediately. Here, you use physical strength.”

The engines are 125 years old (made in Glasgow) and sometimes break down. In the film, Chettri fixes one such problem, where he takes care of a leaking cylinder by covering it with a potato chips wrapper and fastening it with a wire. Says Bhartiya, “The journey this train makes is extraordinary: a vertigo-inducing 7,000 feet climb in 52 miles. Equally extraordinary is the life of people here.”

Some 23 fans in England got together after watching this film to help Sita Chettri with her children’s education. They opened a bank account and deposited some money. Her five sons are thrilled with the support and the sudden fame. But when I phoned the Chettri family at seven in the morning, her son Kedar informed me that she had already left for work. Her new-found fame did not matter. What she did, as she carried people’s luggage up the hill every day, like a modern-day Sisyphus, was earning enough to put her sons through college.

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy

Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy![submenu-img]() RCB cancels practice, press meet after threat to Virat Kohli's security ahead of IPL 2024 eliminator: Report

RCB cancels practice, press meet after threat to Virat Kohli's security ahead of IPL 2024 eliminator: Report ![submenu-img]() Meet Indian-origin man, IIT alumnus who is world's second-highest paid CEO, his salary per day is...

Meet Indian-origin man, IIT alumnus who is world's second-highest paid CEO, his salary per day is...![submenu-img]() RBI approves Rs 2.11 lakh crore dividend payout to Indian govt for 2023-24

RBI approves Rs 2.11 lakh crore dividend payout to Indian govt for 2023-24![submenu-img]() Mozz Guard Mosquito Zapper Reviews (Zap Guardian): Side effects, ingredients benefits, price

Mozz Guard Mosquito Zapper Reviews (Zap Guardian): Side effects, ingredients benefits, price![submenu-img]() IIT graduate builds Rs 1057990000000 company, leaves to get a job, now working as a….

IIT graduate builds Rs 1057990000000 company, leaves to get a job, now working as a….![submenu-img]() Indian Air Force Agniveervayu Recruitment 2024: Registration starts today, know eligibility, steps to apply

Indian Air Force Agniveervayu Recruitment 2024: Registration starts today, know eligibility, steps to apply![submenu-img]() Meet woman who was married at 16, faced domestic abuse, did odd jobs as single mom, became IAS officer, is posted at...

Meet woman who was married at 16, faced domestic abuse, did odd jobs as single mom, became IAS officer, is posted at...![submenu-img]() Maharashtra HSC 12th 2024: Result declared, know how to check

Maharashtra HSC 12th 2024: Result declared, know how to check![submenu-img]() Meet man who topped IIT-JEE, studied at IIT Bombay, then went to MIT, now is...

Meet man who topped IIT-JEE, studied at IIT Bombay, then went to MIT, now is...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer

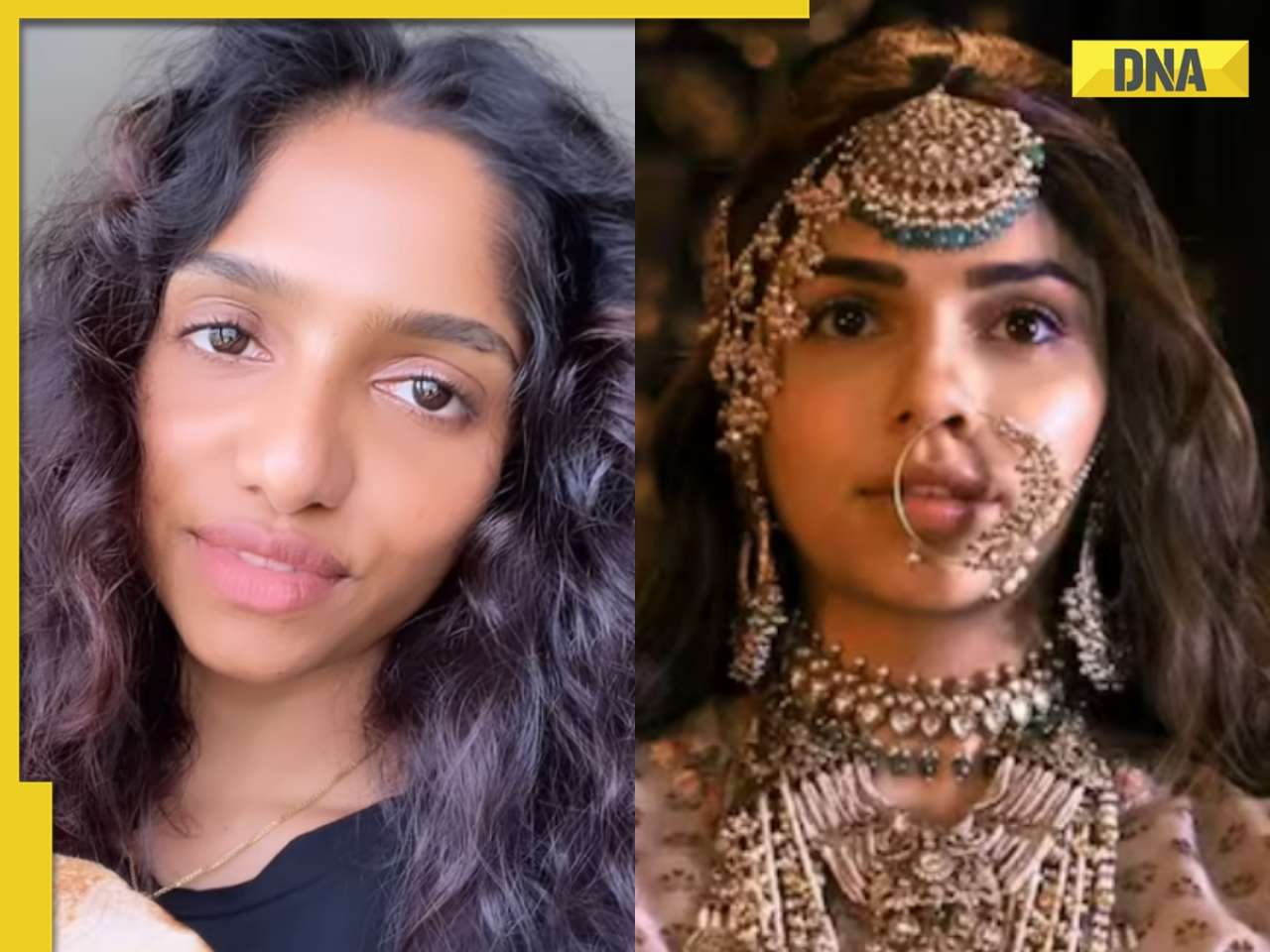

AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer![submenu-img]() Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet

Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024

Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'

Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'![submenu-img]() Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024

Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() Watch: Kapil Sharma's daughter complains as paps click her photos in viral video, says 'papa aapne kaha tha ki...'

Watch: Kapil Sharma's daughter complains as paps click her photos in viral video, says 'papa aapne kaha tha ki...'![submenu-img]() Watch: Anil Kapoor hijacks The Great Indian Kapil Show, Farah Khan reveals which actor is 'most kanjoos' in Bollywood

Watch: Anil Kapoor hijacks The Great Indian Kapil Show, Farah Khan reveals which actor is 'most kanjoos' in Bollywood![submenu-img]() Manoj Bajpayee reveals why Anurag Kashyap didn’t work with him for 14 years: ‘My career was going down, he didn’t...'

Manoj Bajpayee reveals why Anurag Kashyap didn’t work with him for 14 years: ‘My career was going down, he didn’t...'![submenu-img]() Sanjay Dutt quits Welcome 3 after fallout with Akshay Kumar? Report says he walked out after first day because...

Sanjay Dutt quits Welcome 3 after fallout with Akshay Kumar? Report says he walked out after first day because...![submenu-img]() Allu Arjun enjoys lunch with wife Sneha at dhaba; fans hail his ‘simplicity’ despite Pushpa success

Allu Arjun enjoys lunch with wife Sneha at dhaba; fans hail his ‘simplicity’ despite Pushpa success![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy

Viral video: Woman tries to cook omelette on road, internet is not happy![submenu-img]() Groom saves bride from unexpected milk bath during haldi ceremony, viral video melts internet

Groom saves bride from unexpected milk bath during haldi ceremony, viral video melts internet![submenu-img]() Viral video captures epic showdown between two king cobras, watch who wins

Viral video captures epic showdown between two king cobras, watch who wins![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman's 'Senorita' dance steals hearts during RCB vs CSK match in Bengaluru, watch

Viral video: Woman's 'Senorita' dance steals hearts during RCB vs CSK match in Bengaluru, watch ![submenu-img]() Viral video: Lion's terrifying ambush on napping wildebeest stuns internet, watch

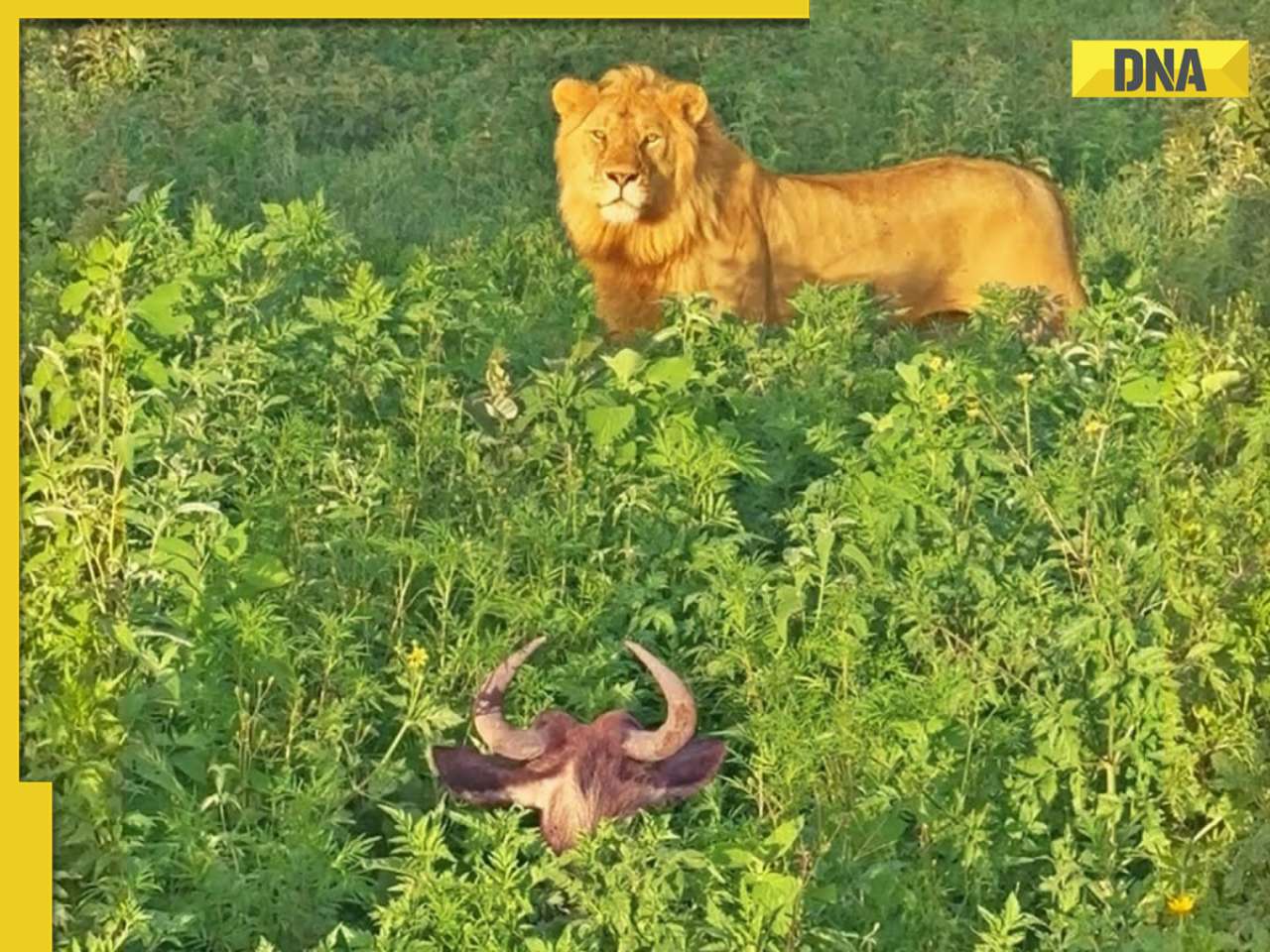

Viral video: Lion's terrifying ambush on napping wildebeest stuns internet, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)