As Shashi Mane, the in-house editor at BR Studios, dusts an old film print before laying it up on a Steenbeck to show how it works, he’s rueful that the machine is the only one left.

Tin cans carrying film rolls are out of fashion. As the film industry gets tech savvy, digital consoles have replaced manual machines. Aniruddha Guha takes a look at both, the new and the defunct

As Shashi Mane, the in-house editor at BR Studios, dusts an old film print before laying it up on a Steenbeck to show how it works, he’s rueful about the fact that the machine is the only one left with them. “There was a time when we had a number of these and work would be on day and night. Now this is the only one. The others have been replaced with newer digital editing tools like the Final Cut Pro.” Mane however mentions that some editors — “the old-timers” — still prefer working on the manually operated German machine, Steenbeck, which the film industry had been using since the 70s. BR Studios, therefore, retained the one, which they bought in 1984.

The Steenbeck was replaced with computerised software, known as Avid in the late 90s and now, newer software programmes like the Final Cut Pro are used. “When editors realised around ten years back that most of the work would have to be done on an Avid, they were reluctant to accept the format,” says Omkar Bhakri who has edited

National award-winning Punjabi films Des Hoya Pardes and Shaheed-E-Mohabbat Boota Singh. The Steenbeck relied more on the perfection and talent of the editor, rather than depending on computer-assisted technology. Although he says that “the perfection achieved on a Steenbeck cannot be done so on a computer system”, he is ready to give credit to the newer, more widely used form of editing. “Once you get a hang of the software, working on it becomes much easier. Also, work is done much quicker now than the old days.”

The old has given way to the new in every department of film production, be it editing, cinematography or sound engineering. Veteran sound recordist, Rakesh Ranjan learnt the art in FTII, Pune before graduating in 1976. All these years, he has adjusted to changes and improvements in audio consoles - the workshop of a sound engineer. “Getting accustomed to technology is part and parcel of a professional. It may take some time to get used to more fancy equipments, but in the end they only facilitate a better job.”

After working for years on the ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’ machine, which involved ‘rolling’ the film manually for the purpose of sound editing, Ranjan is now very happy with the digital Harrison console. “The digital audio has been a boon for us. Earlier a production van with boxes of rolls had to be sent to various studios, where all the work was done manually. Today computers allow all that data to be carried in an 8GB drive,” says the recordist of films like Asoka, Pardes and the recently released Race.

In cinematography, some of the innovations are revolutionary—the Helicam for instance. It was used in U Me Aur Hum, directed by Ajay Devgan. A ‘flying’ camera attached to a helicopter and operated by a remote control, the Helicam enables the cinematographer to capture images at a high altitude by maneuvering the heli-cam to achieve desired results. In this case it was Aseem Bajaj, the Director of photography (DOP) of films like Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, Shabd and Chameli.

“We cinematographers can only experiment as much as our producer’s budget allows.

In a scenario where most Indian producers don’t exactly recover their money, I don’t blame my producer for not giving me top of the line equipment,” says Bajaj, who admits that though most DOPs shoot with an Arri435 today, he himself uses the more expensive Panavision camera. However, Bajaj believes that the market in India is much better today and even western countries are looking for technologies here. With film still being image capturing media, Bajaj is waiting for the entry of digital cameras, which according to him will take around five more years.

While technicians have had to deal with newer equipment, it’s the suppliers who have had to keep themselves abreast with changes around the world. “It’s a must today,” says Vikram Mehrotra of Legend Films, which supplies equipment to film units. “I travel abroad regularly to check on the equipment used there. A good deal of research is done on the internet too, and with the best technology being used by filmmakers today, there’s no other choice but to provide it to them,” says Mehrotra, who also produced the Shah Rukh Khan starrer, Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa.

BR Studios, which provide some of the best editing and audio consoles, have always had to update their editing and dubbing rooms with newer technology. The first to introduce the Rock ‘n’ Roll system, filmmaker Ravi Chopra of BR Studios, believes that audio consoles in India have improved by leaps and bounds. “When I made The Burning Train in 1980, I had to get the film’s entire sound engineered in London, because a good enough system didn’t exist in India. Today, we are able to make products that can compete with the best in the world,” he says.

g_aniruddha@dnaindia.net

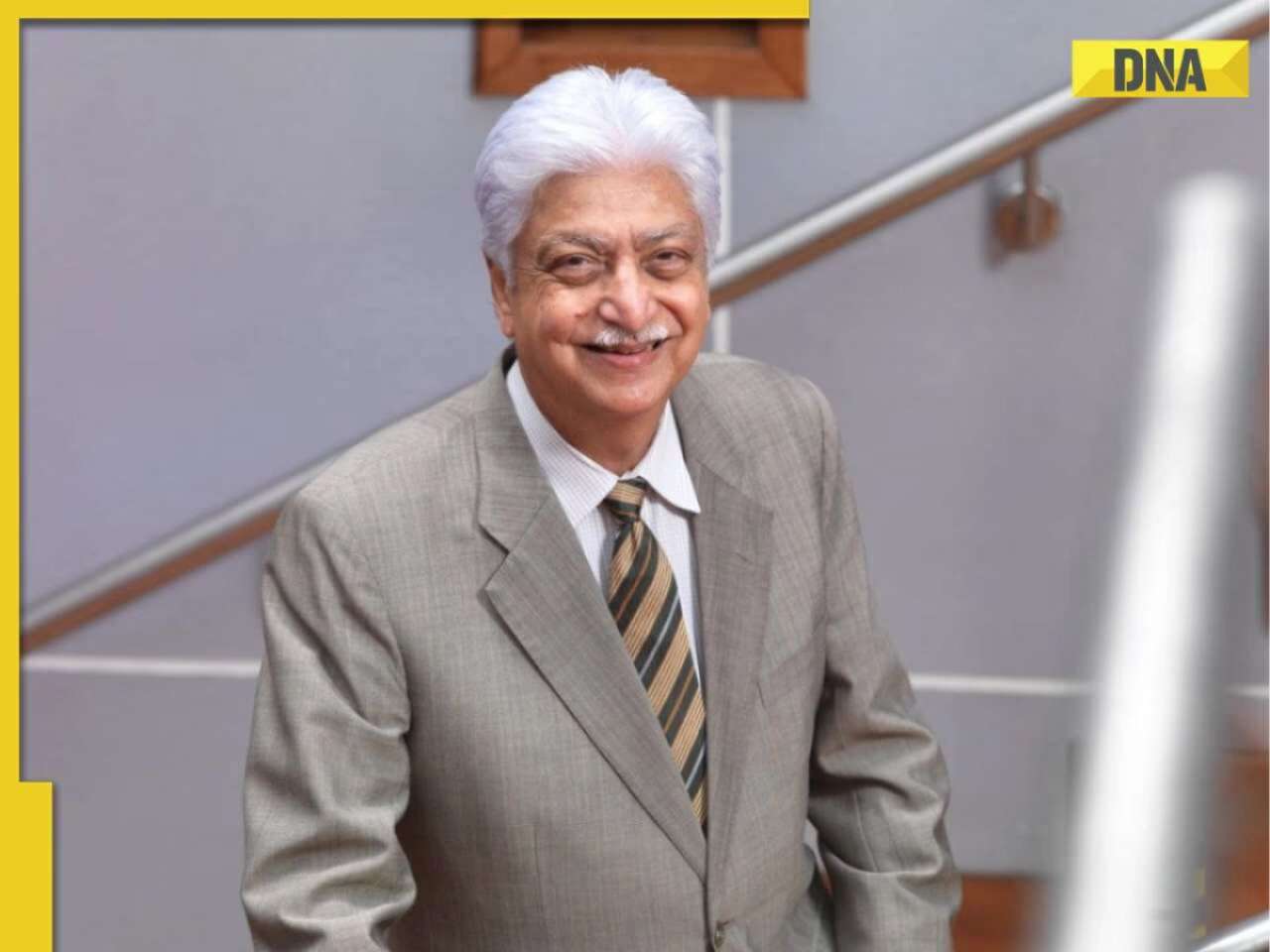

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)