In his latest book, Slavoj Zizek, launches a spectacular attack on the ideological twin towers of the contemporary global order — liberal democracy and capitalism.

In his latest book, the Slovenian superstar of cultural theory, Slavoj Zizek, launches a spectacular attack on the ideological twin towers of the contemporary global order — liberal democracy and

capitalism — and demonstrates how the denial of ideology is the ultimate proof that we are more than ever shaped by ideology, writes DNA.

Slavoj Zizek has been hailed as ‘the Elvis of cultural theory’. He’s also been described as the ‘the most dangerous philosopher in the West.’

This book offers ammunition to both those tags. In a rollicking analytical tour de force that is as sweeping in its scope as entertaining in its insights, the Slovenian theorist targets the twin towers of the contemporary global order — liberal democracy and capitalism — to devastating effect.

He begins, and ends, his book by issuing a clarion call for a return to communism: “You’ve had your anti-communist fun, and you’re pardoned for it — time to get serious once again.” Serious-minded people can never make up their minds how seriously to take him, if at all.

Zizek is professor of philosophy at the University of Ljubljana in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. Unlike professors in other countries, Zizek doesn’t have to teach. His government, which considers him a cultural ambassador, pays him to write books and travel the world giving lectures.

Understandably, he has turned down many lucrative offers for professorship from American universities. (“Why, if you have a job where you do nothing, would you change it for a job where you have to do something?” he told an interviewer.) And earlier this month, he was on a lecture tour in India.

Zizek’s work straddles philosophy, psychoanalysis, and culture studies. His own term for what he does is ‘a critique of ideology.’ Now, if you happen to be someone who thinks you are ‘beyond ideology’, because you subscribe to no ideology whatsoever, then you are the perfect target audience for this book. Zizek explains why: “On account of its all-pervasiveness, ideology appears as its own opposite, as non-ideology, as the core of our human identity underneath all the ideological labels.”

And the magical screen that makes our ideology invisible is the “richness of [our] inner life” — the stories we tell ourselves.

One of the examples Zizek cites to illustrate the functioning of capitalist ideology is that of Bernard Madoff, the highly successful investment manager and philanthropist from Wall Street who was arrested for running a $50 billion Ponzi scheme.

He says that Madoff’s was not a pathological case, a “rotten worm” in the healthy green apple of capitalism, but an extreme and therefore “pure example” of capitalism’s inner logic, and how it caused the financial breakdown. He therefore finds the attempts to pathologise Madoff to be ideological operations.

“Did Madoff not know that, in the long term, his scheme was bound to collapse?”asks Zizek. “Then what force denied him this obvious insight?” Zizek offers his answer: “Not Madoff’s own personal vice or irrationality, but rather…an inner drive to go on, to expand the sphere of circulation in order to keep the machinery running, inscribed into the very system of capitalist relations. In other words, the temptation to ‘morph’ legitimate business into a pyramid scheme is part of the very nature of the capitalist circulation process.”

Zizek then shows how ideology kicks in to save capitalism, as he talks about the moral injunctions that came pouring out in the immediate aftermath of the financial meltdown, to fight against the culture of excessive greed. “The compulsion (to expand) inscribed into the system itself is translated into a matter of personal sin, a private psychological propensity…”

Greed, therefore, is not so much an individual character trait here, but a transfer of the system’s logic onto the psychology of the individual, so that the ideological underpinning of capitalism is rendered invisible, behind the screen of ‘human nature’.

One of Zizek’s more famous analogies points up the crisis of liberal democracy. In an elevator, the ‘door close’ button does nothing to close the door but merely gives the presser a false sense of doing something.

Similarly, a citizen who votes imagines that he is participating in the political process, but in effect, the consensus between the major parties on most key issues leaves the voter with no real choice.

But voting, like button-pressing, gives you a sense of involvement. Zizek goes on to explain how parliamentary democracy works on the basis of passivisation of the majority, and why always the power of the executive keeps growing, in the direction of the emergency state.

Every ordinary citizen, he argues, “is effectively a king — but a king in a constitutional democracy, a monarch who decides only formally, whose function is merely to sign off on measures proposed by an executive administration.” So this is the basic problem of liberal democratic ideology: “How to maintain the appearance that the king effectively makes decisions, when we all know this not to be true.”

The ‘tragedy’ and ‘farce’ in the title of the book refer to the two events that mark the beginning and the end of the first decade of the 21st century: the 9/11 terror attack in 2001, and the financial meltdown in 2008. The Bush administration, points out Zizek, responded to both these events in much the same way: “Both times Bush evoked the threat to the American way of life and the need to take fast and decisive action to cope with the danger. Both times he called for the partial suspension of American values (guarantees of individual freedom, market capitalism) in order to save these very same values.”

Zizek uses these two events — one, symptomatic of the crisis of liberal democracy, and the other, of capitalism — to frame his critique of ideology. And his pet technique is to pile up the paradoxes: freedom is to be saved by suspension of freedom; market capitalism is to be saved by state socialism; pauperised home owners are to be saved by saving the rich bankers, and so on.

At times, the paradoxes, even as they set in relief the cynical manipulativeness at work, can be hilarious. Zizek quotes from a New York hotel’s advisory for guests, “Dear Guest, To guarantee that you will fully enjoy your stay with us, this hotel is totally smoke-free. For any infringement of this regulation, you will be charged $200.” And here’s our man’s take on it:

“The beauty of this formulation, taken literally, is that you are to be punished for refusing to fully enjoy your stay.” That’s Zizek in his element.

While his references to Hegel, Marx and Lacan may seem scary at first, for those ready to negotiate those thickets, this little adventure in Zizekland is a trip worth making.

![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'

Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...

Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...![submenu-img]() 'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral

'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts

Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts![submenu-img]() Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh

Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan

In pics: Ram Charan gets mobbed by fans during his visit to Pithapuram for ‘indirect campaign’ for uncle Pawan Kalyan![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Yodha, Aavesham, Murder In Mahim, Undekhi season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, Sonali Bendre celebrate 25 years of Sarfarosh, attend film's special screening

Aamir Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, Sonali Bendre celebrate 25 years of Sarfarosh, attend film's special screening![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'

Aamir Khan was unsure if censor board would clear Sarfarosh over mentions of Pakistan, ISI: 'If Advani ji can say...'![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...

Gurucharan Singh missing case: Delhi Police questions TMKOC cast and crew, finds out actor's payments were...![submenu-img]() 'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral

'You all are scaring me': Preity Zinta gets uncomfortable after paps follow her, video goes viral![submenu-img]() First Indian film to be insured was released 25 years ago, earned five times its budget, gave Bollywood three stars

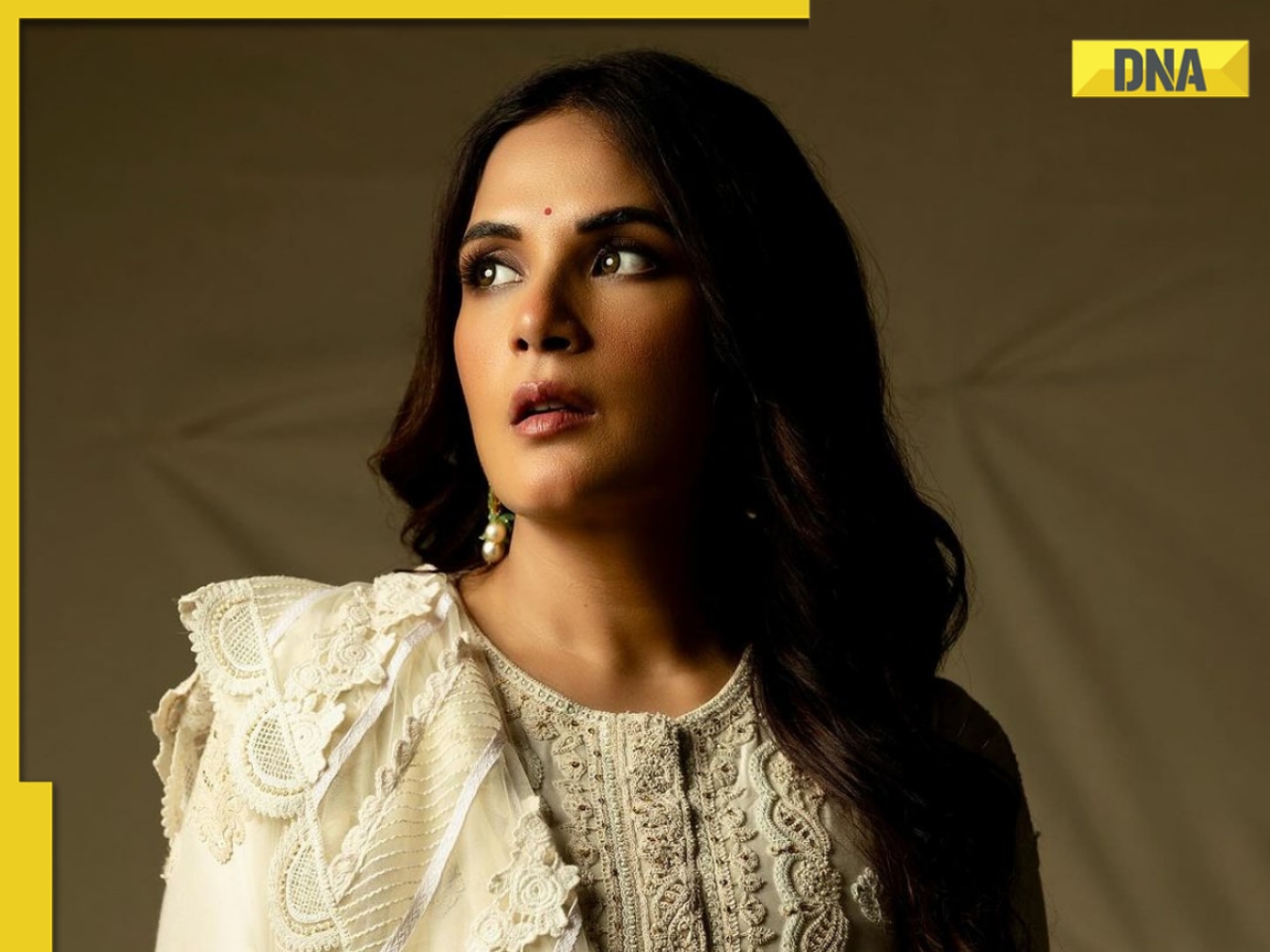

First Indian film to be insured was released 25 years ago, earned five times its budget, gave Bollywood three stars![submenu-img]() Mother’s Day Special: Mom-to-be Richa Chadha talks on motherhood, fixing inequalities for moms in India | Exclusive

Mother’s Day Special: Mom-to-be Richa Chadha talks on motherhood, fixing inequalities for moms in India | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Kolkata Knight Riders become first team to qualify for IPL 2024 playoffs after thumping win over Mumbai Indians

Kolkata Knight Riders become first team to qualify for IPL 2024 playoffs after thumping win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: This player to lead Delhi Capitals in Rishabh Pant's absence against Royal Challengers Bengaluru

IPL 2024: This player to lead Delhi Capitals in Rishabh Pant's absence against Royal Challengers Bengaluru![submenu-img]() RCB vs DC IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs DC IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() CSK vs RR IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs RR IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Delhi Capitals

RCB vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts

Viral video: Influencer dances with gun in broad daylight on highway, UP Police reacts![submenu-img]() Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh

Family applauds and cheers as woman sends breakup text, viral video will make you laugh![submenu-img]() Man grabs snake mid-lunge before it strikes his face, terrifying video goes viral

Man grabs snake mid-lunge before it strikes his face, terrifying video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man wrestles giant python, internet is scared

Viral video: Man wrestles giant python, internet is scared![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi University girls' sizzling dance to Haryanvi song sets the internet ablaze

Viral video: Delhi University girls' sizzling dance to Haryanvi song sets the internet ablaze

)

)

)

)

)

)