Social activists, doctors, lawyers and even an acid attack survivor share their perspectives on combatting acid attacks

Every year, an estimated 80% of the globally reported 1,500 acid attacks are directed at women. Rejected suitors and husbands are predominantly the perpetrators. However, there is no official source to corroborate this. “We can’t keep waiting for things to happen, for a law to be passed, for adequate compensation or punishment to be dispensed. So, we do what we can,” says Alok Dixit, former journalist and founder of Stop Acid Attacks, an organisation that is attempting to compile a database by reaching out to acid attack victims across the country, using international crowd-funding websites like indiegogo.com to fund surgeries.

Medically Speaking

“The first thing to do is to wash the acid affected area with water,” says Dr. Sunil Keswani, cosmetic surgeon and secretary of the National Burns Centre. “Keep pouring water for 20-30 minutes to wash off all the acid and reduce the time that the acid is in contact with the skin. Rush the person to the nearest doctor and then to the closest burn hospital. Skin should be grafted onto burn victims within a day or two to prevent infections. Regrettably, we don’t have adequate burn centres or skin collection centres in India and the municipal centres are not exactly well-equipped. We have two burn centres in Mumbai, but what about the rest of India?”

Psychological Concerns

Shock, anger, self-pity and acceptance are the emotions that surface in the aftermath of an acid attack, according to Dr. Maya Kripalani, consulting psychologist and family therapist, at the Jaslok and Bhatia hospitals in Mumbai. “These feelings are normal and must be accepted, not denied. Avoid blame games. Families need to be supportive and let the victims grieve. Time and patience are crucial. People who learn to channelise their anger heal faster than those who get caught up in self pity.”

By Law

“We had no separate law taking cognizance of acid attacks as a distinct crime until 2013, when amendments A & B were inserted in Section 326 of the Indian Penal Code,” says Dr. Subhas Chakraborty of the Acid Survivors Foundation India (ASFI), which has been campaigning for an Indian version of Bangladesh’s Acid Crime Prevention Act and Acid Control Act, 2002. This would require a license to manufacture, sell or purchase acid and also make it mandatory to maintain sales records.

“There are two aspects to the law with regard to acid attacks. One is punishment. The other is compensation,” explains advocate and women’s rights activist Flavia Agnes. “However, perpetrators are not always apprehended; while Karnataka and some other states have compensation schemes, Maharashtra still does not. ” State governments offer compensations ranging from Rs.2,00,000 to Rs.3,00,000, which are meagre compared to the “Rs.50,00,000 to Rs.75,00,000,” that Dr. Keswani informed us is the treatment expenditure incurred by an acid attack victim over a lifetime.

Society Says

Just about everybody we spoke to agreed that the government should adopt stricter laws for licensing acid and acid byproducts and that the punishment meted out to assailants should be more severe to deter attacks.

“Acid attacks are worse then rape,” emphasizes advocate and women's rights activist Flavia Agnes. “While rape may mar what Indians are conditioned to believe is the 'dignity' of a women, an acid attack burns away her identity altogether.”

Dr Keswani draws to our attention to the fact that, “Pretty women are the targets of most acid attacks. The scars go deeper than surgery. I have watched personalities change. Extroverts turn into introverts and isolate themselves from friends and society.”

“I don't think acid attacks have anything to do with being pretty. It's just a case of a man trying to dominate a woman who is too independent to obey him,” says acid attack survivor Haseena Hussain.

Do women recover enough to get back into the mainstream? “Yes, they do,” says Dr Maya Kripalani. “They brave the sidelong glances and whispered conversations, because they are determined too. Beauty is not just skin deep. We women are so much more than our faces.”

A Survivor's Tale

In the summer of 1999, Haseena Hussain was just another girl growing up in a middle-class home in urban India. She was a data-entry operator, doing a correspondence course in commerce but hoped to become a Bollywood fashion designer. All that changed in April 1999, when her former employer, whose proposal she rejected, splashed acid on her. “I felt helpless,” exclaims Haseena. “People don’t know what to do when they see you standing there screaming in pain. They are afraid to help in situations that might involve the police.”

What dragged her out of darkness and back to life? “Justice!,” she says, “I wanted justice. I kept telling my doctors to finish off the surgeries quickly, so that I could go to court.” The Human Rights Legal Network (HRLN) and Campaign and Struggle Against Acid Attacks on Women (CASAAW) supported her battle.

Has she received justice? Not quite. “The best that the Indian courts offer is a 14-15 year life sentence. Justice is life imprisonment until death,” she says. The Rs.2 lakh that she received from the government couldn’t even cover treatment costs. Even after her parents’ home and jewellery were sold off, funds raised by local media and NGOs were required to pay for the 35 surgeries she had between 1999 and 2009. What’s worse is her allegation that, “People use my name to raise funds which never come to me.”

Does the unfairness of it all consume her? “No. The past is the past,” she says. There’s a calm acceptance to her voice. No one would know she’s been to hell and back. There was a time when her fingers had melted together, she couldn’t move them and had to be fed. “Almighty Allah and my family helped me through the torture,” she confides.

Her neck still hurts from the stretching of all the grafted skin. She covers her face while travelling, to minimize the risk of infection. She’s had essential surgeries but not cosmetic ones, because, “It’s painful. I think 35 surgeries is more than enough. Besides, what’s the point? I can’t see my face.” Did the thought of committing suicide ever cross her mind? “No!” she insists. “Suicide would mean that I had failed. Why should I sit in a corner and cry? Why should I let anyone throw my world into darkness, for no fault of my own?”

It’s terrifying for a sighted person to step back into their lives unsighted. It wasn’t until 2009 that a course at Enable India opened up a world of possibilities for Haseena. She checks her email, surfs the net, and responds to smses with the help of programmes designed to help the visually impaired. She manages the house, cooks for herself, and has secured a government job on merit. Haseena has done the rounds of government offices to show people what she looks like, as she feels people don’t realise the damage that acid can do till they see you. “How can we get jobs in the private sector when people can barely look at us?” asks Haseena.

“I wanted to be independent. I wanted my parents to be happy that I could take care of myself. I travelled 50 km a day to study, even when people suggested I shouldn’t. But my whole life is a struggle,” says the spirited girl who derives much satisfaction from reaching out to the visually impaired. She hopes to do a course in counselling to help other victims.

Maybe she’s braver and wiser today, but she’s still the same girl who loves to keep track of trends. Only now, she has to ask her mum to describe the world outside.

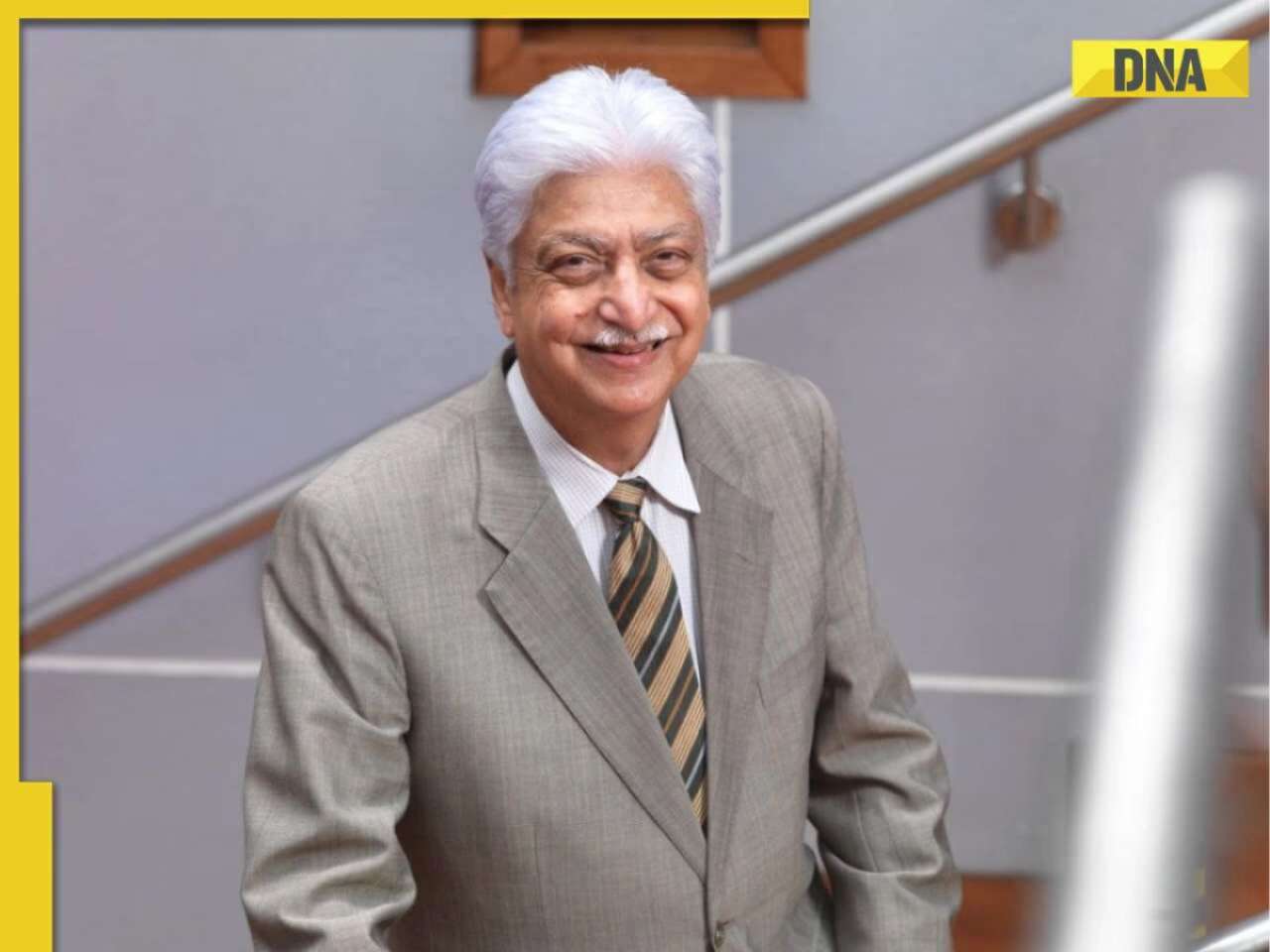

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)

)