Despite the onslaught of television and a paucity of funds, puppetry as an Indian art form continues to hold its ground, finding new ways of survival.

It is a fairly common refrain in culture circles that television is killing traditional Indian art forms. And yet, it might come as a surprise that the resurrection of puppetry, arguably one of the oldest story-telling tropes in the country, can in large part be attributed to the idiot box.

Puppetry as an art form finds early mentions in India’s classical texts. One of the earliest references to puppetry is found in the Tamil classic Silappadikaaram written around the 1st or 2nd century BC. One of India’s greatest grammarians, Patanjali, refers to puppetry in his defining work on Sanskrit grammar, Mahabhasya, as being one of three dramatic genres. The concept of puppetry can also be found in the Bhagvad Gita, one of India’s most revered philosophical treatise that is part of the Mahabharata, which itself is steeped in antiquity.

As other art forms such as drama and dance took stage, live puppetry shows gradually took a back seat; today, it lives on in as a super-specialty of sorts, practised only by a handful, watched by even fewer.

“Even now when we travel in villages, the older people appreciate the art and tell us that they always wait to see us but not a single child sits down and sees the art we perform. After the increase of electronic channels people get to see it on screen whenever they want, there are few people who like to see the live shows,” rues Puran Bhat, a resident of Kathputli Colony—literally, Colony of Puppeteers—in New Delhi.

However, Bhat, who learnt the art when he was 9, insists that the form itself is not dying, just that the viewership has been reduced due to television and cinema.

At the same time, there are those who maintain that puppetry has got a second lease of life, thanks to television.

Call it the Seventies’ puppet equivalent of India’s Got Talent, but one of Mumbai’s oldest and most famous puppets may owe his longevity to TV.

‘Ardhavatrao’, a puppet character created by Yeshwant Keshav Padhye in 1916, and modelled on an eccentric middle-class Marathi man, imagined and created in 1916, might have had a shorter lifespan if it weren’t for TV—he gained a mass following after Doordarshan called Padhye’s son Ramdas in 1972 to do a 15-minute show, giving the puppet his first break on national TV.

“Ardhavatrao became famous in every household after the Doordarshan show was telecast,” admits 70-year-old Ramdas.

On September 24, he opened a new live show—‘Carry on Entertainment—Ramdas Padhye Live’ as a part of Adhavatrao’s centennial birthday celebrations, involving the entire Padhye family, along with 50 puppets and featuring the 40 best acts over the life of the show.

“Ardhavatrao is now the eldest member of our family. Since the beginning, all my puppets were kept in my studio but I always keep ‘Ardhavatrao’ and his wife Awadabai close to me, in my house,” says Padhye.

Another popular Mumbai ventriloquist/puppeteer, Rajkumar Javkar aka Rajarancho owes his much of his recognition to his first break on the comedy show Laughter Challenge. The 39-year-old mimicry artist earlier worked in a water park before he started acting with his puppet ‘Rancho’, again derived from a popular TV detective serial Raja aur Rancho.

“Ventriloquism is not that popular in India like it is in foreign countries. Television is the best medium to make this art popular but it depends upon the artist’s act and different elements which he uses to make the act entertained,” Rajkumar says.

Puppetry has also found more cross-genre usage, helping it stay alive and relevant.

Mumbai-based self-taught puppeteer Usha Venkatraman, 55, started using puppets to make children understand Indian classical music. In the beginning, Venkatraman used glove puppets since they were easier to manipulate. But after few years, when she saw paper bag puppets in a festival, she got in touch with the Rajasthan-based artist to customise the puppets for her.

“Just by movement, puppets can express themselves. It is a narrative prop to make people understand any story. Besides classical music’s melody and rhythm, I started narrating Indian mythology to the school’s students,” said Venkatraman, who is a trained singer herself.

Venkatraman is also helping to revive the art by helping corporates and college students. For the former, she organises motivational seminars using paper bag puppets. According to her, during these sessions, the puppets’ expressions helps working professionals open up their alter ego, while it helps college students present their presentations in a unique way.

Lack of support

“India has more than 400 types of puppeteers and most of them have died mainly because it was passed down through generations and the new generation wants to stay in the cities for better jobs,” says Shaizia Manekshaw, who conducts puppetry workshops in Mumbai.

“The government’s role is minimal and marginal because only a few of these forms are promoted while many traditional forms did not get proper funding and the authorities do not have knowledge of where they are and how to help these artists.”

Her views are echoed by Anurupa Roy, a member of the de la Marionnette (UNIMA India), who points out that the government has few funds for puppetry due to a lack of knowledge at the grassroots level. “They don’t have proper information about where the families stay in different corners of the country. There is no survey to see the next generations of the puppeter’s family.”

“In every state the condition of puppet art different. At present in Kerala shadow puppet tradition is doing very well. In Tamil Nadu, the leather shadow puppets are not in a good situation because there is just one family left because the traditional and ritual context is gone,” points out Roy.

“In Andhra Pradesh, they have tourism and export industry which buys the puppets. It has become the artefact industry. In some states they have a really good condition while in some states it’s really bad. In Odisha, the condition is not good because there is a problem of poverty but some young generations are modernising it. In West Bengal, it is decreasing because of the quality of the show has fallen. They use Tollywood music because of which the puppet shows lost its vibrant,” she adds.

But Manekshaw also adds that despite old puppet forms dying out, there’s lots happening on the contemporary puppetry scene.

Charting new paths

Some, for example, are keeping the tradition alive not just by making puppets but extending puppet-inspired designs to other handicraft products.

In Andhra Pradesh, for example, the Ramayana and Mahabharata were narrated through leather puppets also known as ‘Tholu Bommalata’. These puppets were earlier made up of deerskin that has now been replaced by goatskin due to its easier availability. Each of the 60 households of Nimmalakunta village in Anantapur district have at least one leather puppet-maker. These artists can make leather puppets anywhere between 15 inches and 7 feet tall. The characters are driven by scripts and demands during the festival season.

Over the past few years, as demand for live shows has fallen, they have branched out to alternative ways to showcase their art.

“Due to TV, there has been decrease in the number of puppet shows since late 90s. Rather than making puppets, we prefer making the art on handicraft materials since it gives us income. Designers from different NGOs come here to teach us various designs which are more in demand in the market,” says 48-year-old Rammana Garu.

“We participate in different exhibitions conducted by government and NGOs. Through this we get orders to customize puppets for our customers and reach out to different people,” he added.

Puppetry is also critical in keeping another art form alive—balladeering. The traditional music is also passed on from one generation to another. “We create our own techniques rather than updating ourselves from others. While we do the puppet manipulation work, we think how it can be done in a different way depending upon the scripts,” says Bhat, who writes his own script and make his own puppets.

“We not only learn to make the puppets but also the music and songs from our elders,” says Ramanna. “When as a child we involve with our family members to make a puppet or during the show, we get to learn from them about the technique of manipulation, dance form while performing the shows, music and songs too. It is in our genes.”

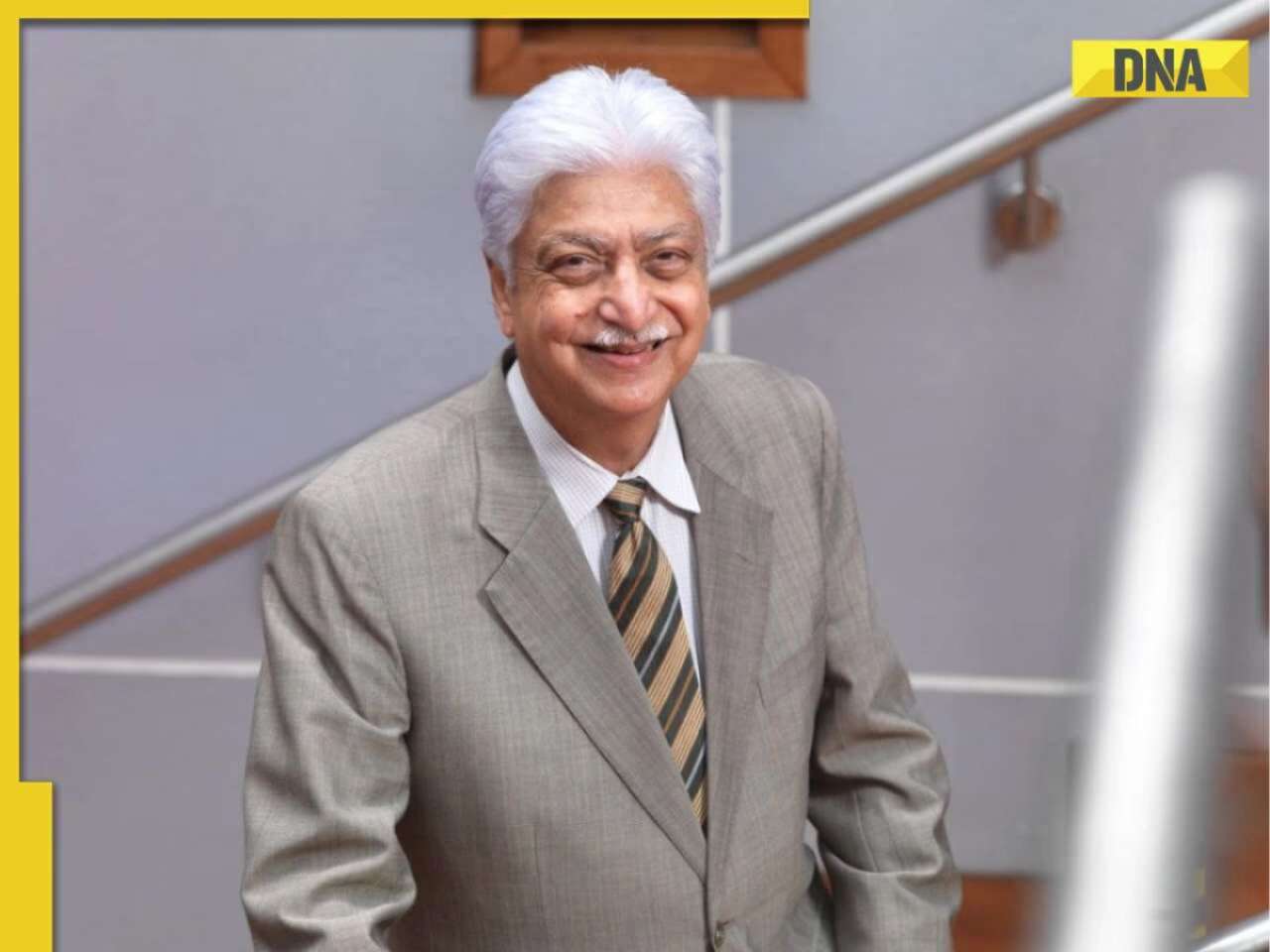

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

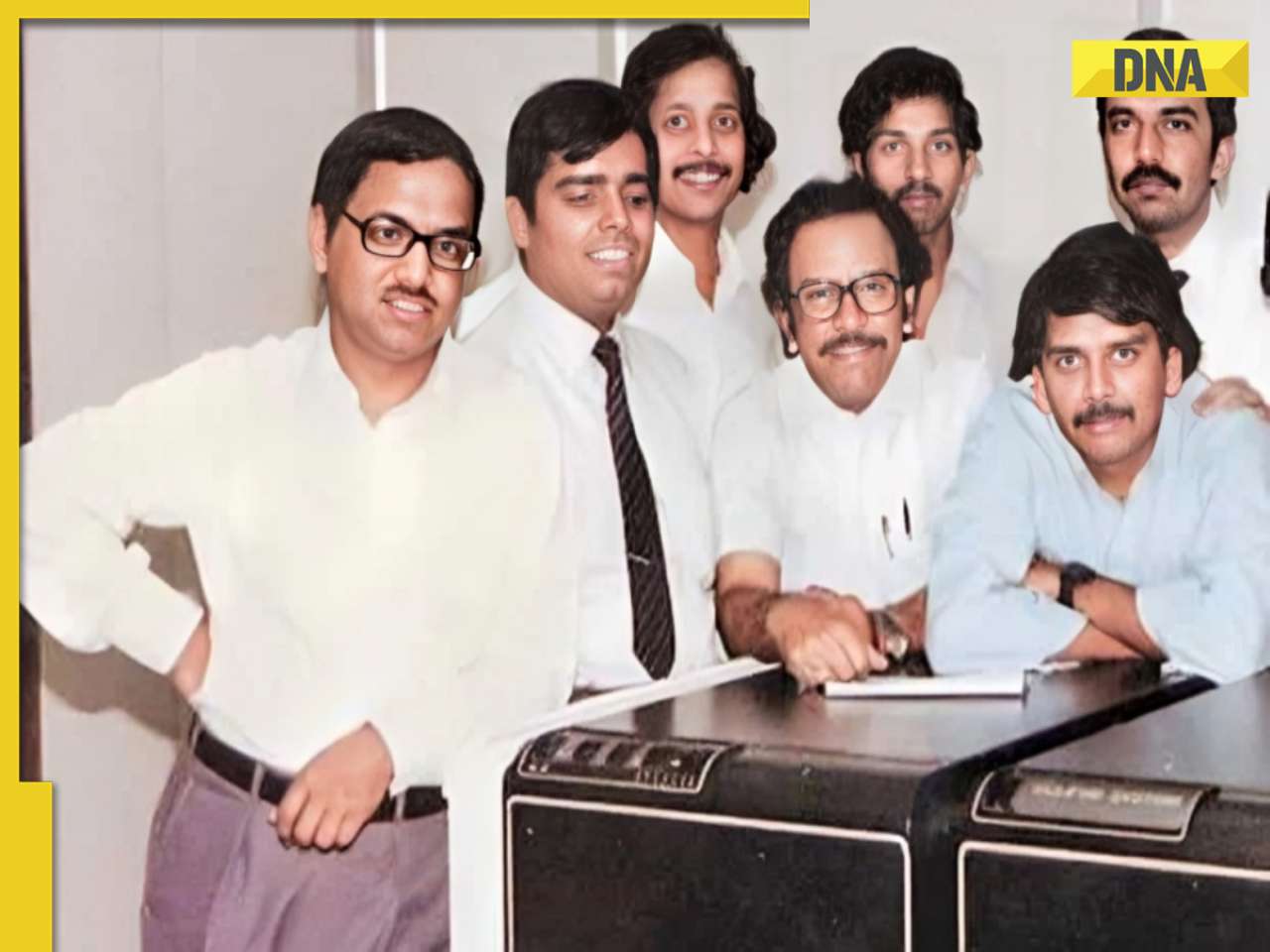

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)

)