The Manganiyars and Langas have for centuries carried on a twin tradition of syncretic, unifying music from the sands of Rajasthan. Yogesh Pawar meets their modern-day representatives whose full-throated voices continue to fill cold desert nights

The setting sun paints the sky in myriad hues, the colours contrasting with the bandhani turbans of the Manganiyar troupe on the open air stage at Jodhpur's Mehrangarh fort. The lead singer, Ghazi Khan Manganiyar, calls out 'dhola re' with a longing that goes straight to your heart, giving you goose bumps. Emotions hidden deep swirl to the surface as the kamaicha, khartal and dholak join in and you wonder if it's only the cold draft blowing in from the desert that makes you huddle in your shawl as you surrender to the embrace of the music.

Post-performance, Ghazi Khan thanks the audience who are full of praise. Asked about the secret of his troupe's enchanting music, he points his hands skywards in supplication and laughs, "In our community, even a new-born lets out his first wail in perfect pitch and scale. Music comes to us as a legacy from the mother's womb."

He suddenly spots Meherdin Langa whose troupe performed before his. They hug warmly, call each other 'ustad,' back-slap and guffaw. Both artists represent not just their communities but a centuries old tradition of music from the desert sands.

"Like the Manganiyars, we too converted from Hinduism during Emperor Aurangzeb's reign. Yet, we traditionally don't touch percussion instruments in keeping with our ancient Sufi tradition. Like the Manganiyars who have their own bowed instrument, the kamaicha, we use the Sindhi sarangi and the algoza ( the double flute), for accompaniment," says Meherdin.

The Langas (literally 'song givers') are an accomplished community of poets, singers, and musicians from the Barmer district of Rajasthan.

Known for their formidable voices, which can leap from the lowest to highest octave in a trice, both the Langas and the Manganiyars are invited to perform at births and weddings. "Our patrons, whom we call kings, are all feudal lords of yore. These wealthy cattle breeders, farmers and land-owners have kept both us and Manganiyars in demand. In exchange for our music, they reward us with grain, wheat, goat, camel, sheep, horse and/or cash."

The 42-year-old Ghazi who breaks into a rhythmic song to illustrate any point he makes, jumps back into the conversation.

"It was the work of Komal Kothari in the mid 70s that brought both our communities to international attention," he says, referring to the late legendary ethnomusicologist from Jodhpur. Khan has never been to school yet his musical sojourns across the world (all of Europe, the US, Brazil, South Africa, Israel, Malaysia, Tokyo and Russia) have taught him enough French, Spanish, English, Hebrew and Russian to hold a conversation. "Language is like music. You stay with it and it begins to seep in," he says humbly, his kohl-lined eyes twinkling with native wisdom.

Yet these nomadic desert musicians were called Manganiyars with contemptuous derision in the past. "The name of our community comes from those who ask for alms," explains Khan, "Through the desert's heat and dust, through its harsh cold winters there wasn't a single occasion when we wouldn't be summoned to our patrons' palaces and havelis to sing and be rewarded. Not only marriages and births, we'd accompany patrons to war and entertainment them and their armies both before and after battles singing ballads of valour and inspiring them. So much so that in the event of the patron's death, the Manganiyars would perform at the ruler's vigil day and night until the mourning was over."

Now the toast of the music cognoscenti, both these groups are practising Muslims whose families trees broke because of Partition in 1947. "Across the border, our patrons are Muslim Sindhi Sipahis, whereas here they are Hindus. While those in Pakistan rue the increasing Wahabisation and fear of radical Taliban which frowns on musical traditions like theirs, here we have our own problems," says Khan. When we try to dig more, he just shrugs his shoulders, "Let it be."

Samandarkhan Manganiyar, from across the border in Umerkot, is more forthcoming on the phone. "The scenario is changing fast. Now we're suddenly being told that this musical tradition which is like breathing, is haram."

His concerns find an echo with Meherdin, who says, "After 1992-93, we see ourselves being stretched from both sides who cannot understand that we are what we are because of our syncretism."

Emboldened, Khan joins in, "The biggest danger comes from the crass commercialisation that Bollywood and TV are bringing in its sway," he says, verbalising his fears for the ancient twin musical tradition which has seen these soulful, full-throated voices fill the cold desert nights for centuries.

Anwar Khan, who has sung for several Bollywood films, says the younger lot doesn't want to take the traditional route of shagirdi before seeking fame or money.

"Today, we see really young children pushed into music reality shows on TV. They burn out quickly and languish forgotten."

He adds, "Our music survived Alexander, Ghazni and the Mughals too. I hope it survives the current onslaught of commerce and communalism too."

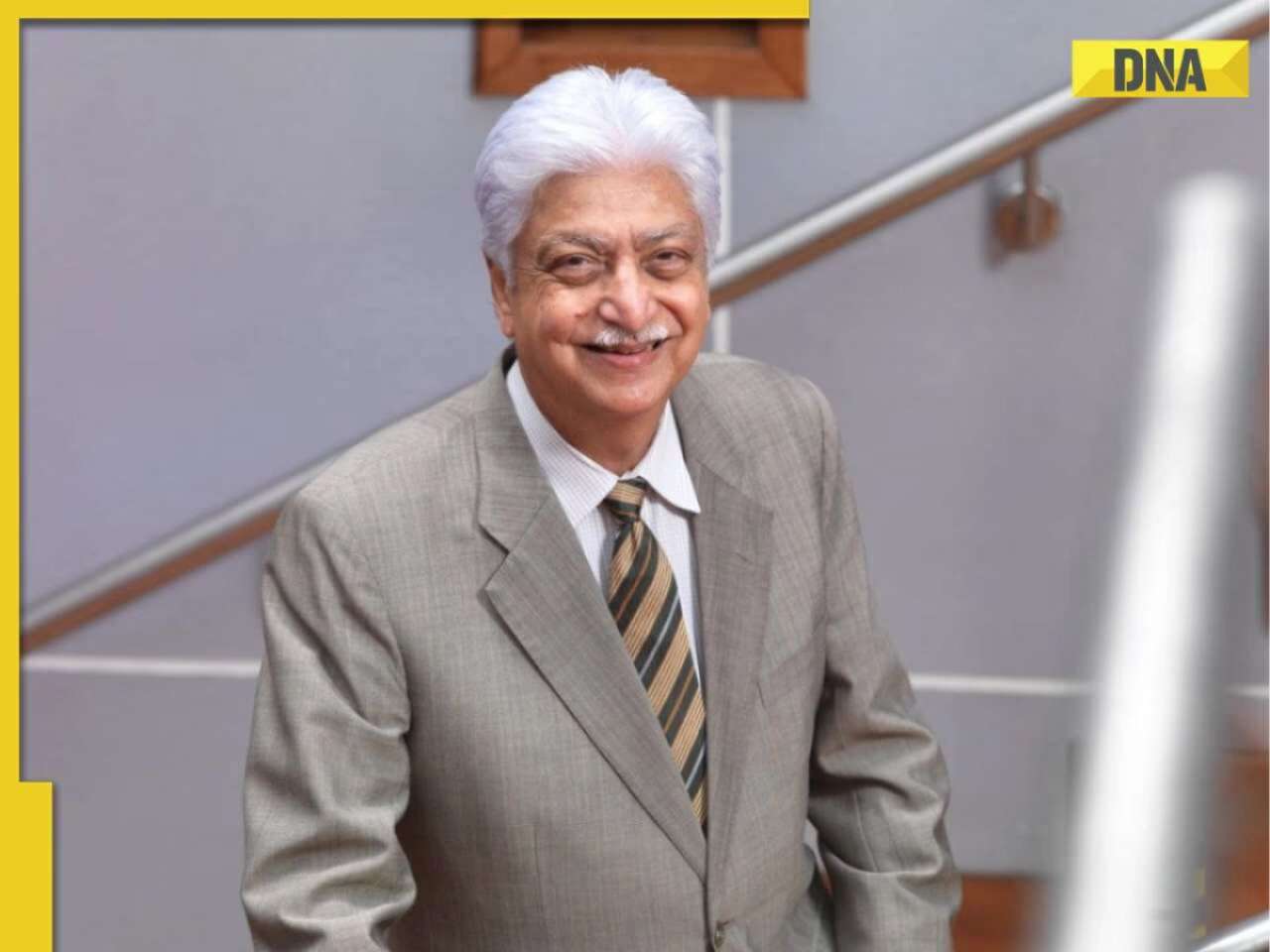

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)

)