The bankruptcy of the visual effects studio behind Life of Pi is a sign of the trouble the industry is in globally. But what exactly ails it? And what does this mean for India? R Krishna finds out

On February 24, Bill Westenhofer, a visual effects supervisor with animation studio Rhythm & Hues, stepped onto the stage to accept an Oscar for the Best Visual Effects for Life Of Pi. It was the studio’s third Academy Award. The first two were for Babe (1995) and The Golden Compass (2008).

But Westenhofer had mixed feelings about the win. A few days before the Oscars, his company had filed for bankruptcy and Westenhofer wanted to highlight the problems the visual effects (VFX) industry was facing in his acceptance speech. The organisers, however, wanted no stories that would dampen the mood, and the sound was abruptly cut-off as he started speaking.

The gesture, criticised by animation and VFX artists across the world, is symbolic of the way things stand in the industry. Over the last few years, complex and cutting-edge VFX used in films like Transformers, Avengers, or Life Of Pi have helped film producers earn gigantic profits. Yet, the studios who enable the supernatural to look realistic, find themselves getting squeezed on margins. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Scott Ross, who co-founded Digital Domain, another big studio that filed for bankruptcy last September, said: “A good year for us was a 5% return.”

This state of affairs has big implications for India, one of the outsourcing hubs for animation and VFX. While news reports in the US have blamed outsourcing to India and other South-East Asian countries for the mess American VFX studios are in, reality is that the situation is equally bad elsewhere in the world.

Moving up the value chain

In the early ‘2000s, animation and VFX was described as the sunshine sector in India. This projection was based on work being outsourced to India, and the fact that US-based studios like Rhythm & Hues were setting up shop in the country.

But recruitment and the volume of work being outsourced hasn’t lived up to expectations, says Raghav Anand, segment champion, Digital Media, Ernst & Young. “The growth of South-East Asian countries as outsourcing hubs is partly responsible for this. Moreover, the quality of production has gone up tremendously. Few studios in India have been able to scale up the skillset of their employees.”

Studios The Mag spoke to confirmed the trend. There is ample competition for low-level work, that includes basics like wire removal (wires that are attached to actors’ bodies during action sequences) and scene clean-ups. Profit margins in such kind of work are slim since studios are ready to undercut the competition.

However, there isn’t as much competition when it comes to higher-end work, such as conversion of a film to 3D, or specialising in complex animations such as the rendering of water. “Companies like ours go for premium projects, where there is a lot of head room. We believe that’s the best way forward,” says Biren Ghose, country head, Technicolor, whose sister concern The Moving Picture Company, has worked on the VFX for movies like Harry Potter, Pirates Of The Caribbean, and Percy Jackson.

Prime Focus, another big VFX player, has started partnering closely with its clients to get better returns. “The work we do today is very different from what we did five years ago,” says Merzin Tavaria, co-founder of Prime Focus, “We are handling complete sequences in many films, from the shoot to final execution of visual effects. We have even moved to converting entire films into 3D.”

The idea is to move up the value chain of filmmaking, which gives the studio a better chance to make money.

Dark side of cheap labour

However, moving up the value chain means having trained staff, who can work on such projects. This is a serious problem.

Industry experts say that while there are hundreds of institutes in India that churn out thousands of students each year, few have the capabilities to take up international projects. Thus, students who get into the animation and VFX space thinking it is a booming industry are in for a shock.

“I’ve been working with a VFX studio for two years. I wasn’t paid a single rupee in the first year,” says Swapnil Patil*, 23. Now he earns just Rs20,000 per month. “Time and money are the two things you don’t get here. I’m working on a TV series that’s set in a magical world. We get raw footage in the morning and barely have a few hours to work on it since the channel needs to broadcast it the same night. I can’t do justice to the work.”

Arun Roy*, 28, who works with one of the big VFX players in India, says his company’s CG division (which handles animation films) is on the verge of shutting down because of lack of work. “I don’t think I will continue in this field for much longer. Even in a studio like Prana, which is doing well, there is so much insecurity. They maintain us on contracts, and if there is no project, we will be laid off. I don’t want so much uncertainty,” says Roy.

The uncertainty isn’t going away soon even as studios experiment with various strategies to stay afloat. “There is an evolution underway,” says EnY’s Anand, “We are going to see a collaborative setup as more studios from the US move into Asia. The bigger studios will get into co-producing films, as well as look at alternate platforms like tablets. The smaller studios, on the other hand, will need to find a specialisation, which gives them the edge over competitors.”

*Name changed on request

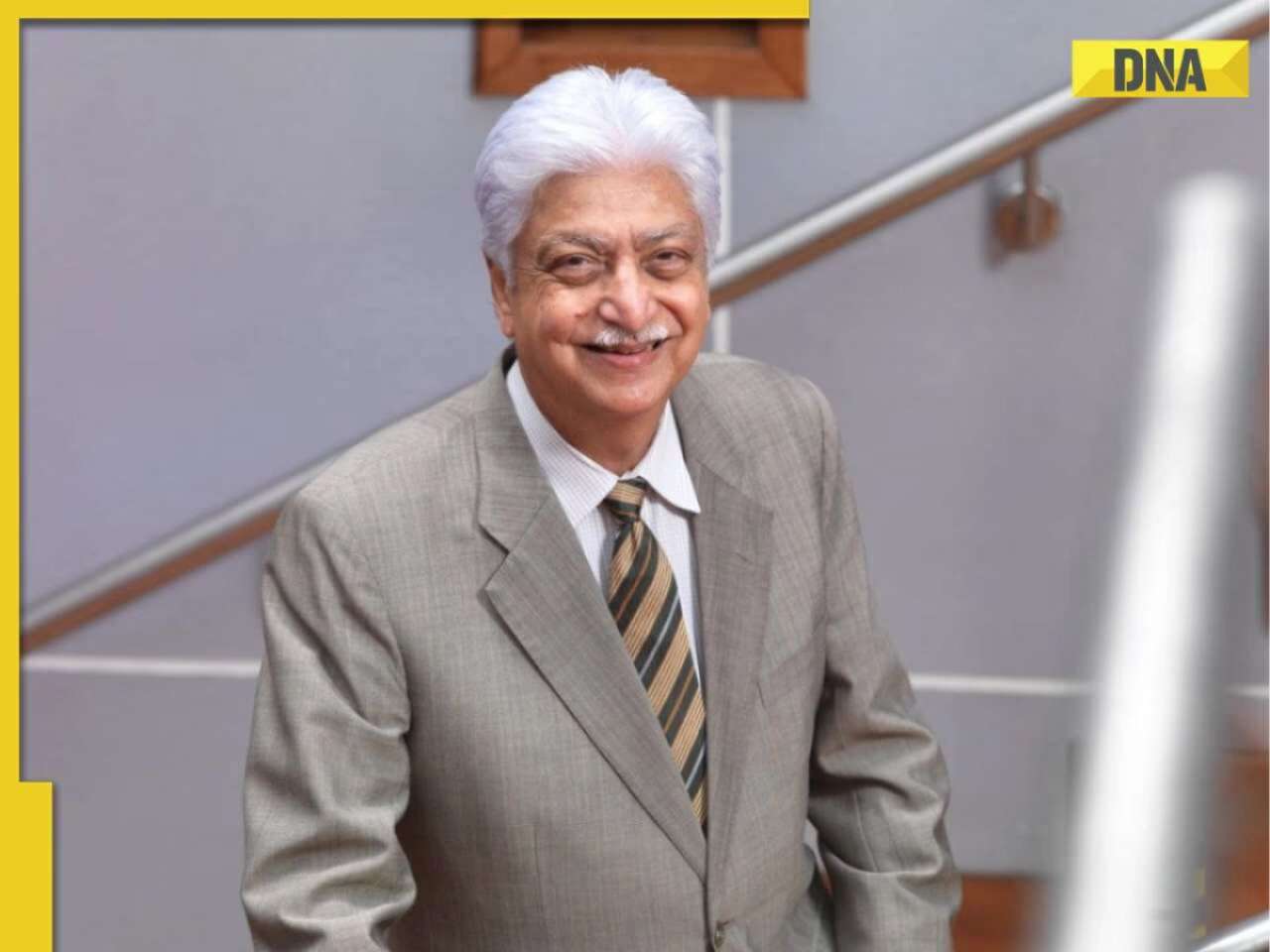

![submenu-img]() Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…

Azim Premji may acquire majority stake in this bank from…![submenu-img]() Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…

Meet schoolmates who quit high-paying jobs to start their own business, invested Rs 1 lakh, now worth Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet daughter of cleaning contractor who cleared UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal

Meet man who was first employee of Infosys, it's not Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, SD Shibulal![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’

Sobhita Dhulipala opens up about facing ‘casual objectification’: ‘I have been told so many times to…’![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta

Meet actress, who debuted with Aamir Khan's film, now winning hearts in Heeramandi; know her connection to Preity Zinta![submenu-img]() Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns…

Meet engineer-turned-actor, who quit high-paying job for acting, struggled to get Rs 200; became superstar, now earns… ![submenu-img]() This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking

This film bombed at box office, earned less than Rs 2 crore, Shraddha Kapoor was first choice, director quit filmmaking![submenu-img]() India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha

India's biggest flop lost Rs 250 crore, derailed 2 stars; worse than Adipurush, Shamshera, Ganapath, Laal Singh Chaddha![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Venkatesh Iyer, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 24-run win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs GT IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans

RCB vs GT IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update

Australia dethrone India to become No. 1 ranked test team after annual rankings update![submenu-img]() Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral

Watch: MS Dhoni's heartfelt gesture for CSK's 103-yr-old superfan wins internet, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man transports huge wardrobe on bike, internet is stunned![submenu-img]() Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart

Mother polar bear cuddles with her cub, viral video will melt your heart![submenu-img]() Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch

Viral video: Girl's 'Choli Ke Piche' dance performance at college fest divides internet, watch![submenu-img]() Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch

Video: Cobra mother's protective instincts go viral as she guards nest of eggs, watch![submenu-img]() Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

Die-hard Virat Kohli fan displays love for 'Namma RCB' at graduation ceremony in US, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)

)