Ajmal Amir Kasab, the poor boy recruited by the Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Faisal Shahzad, the American college degree holder who discovered Islamism, represent two ends of a spectrum of violent jihadis groomed in Pakistan, which can no longer sidestep responsibility for being an export house of terror.

Ajmal Amir Kasab, the poor boy recruited by the Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Faisal Shahzad, the American college degree holder who discovered Islamism, represent two ends of a spectrum of violent jihadis groomed in Pakistan, which can no longer sidestep responsibility for being an export house of terror.

In a week in which one person of Pakistani origin has been accused of plotting New York’s most devastating terrorist attack since 9/11 and another convicted for the barbarity that Mumbai experienced on 26/11, it is pertinent to ask whether the Pakistani Islamist any more conforms to a stereotype. Consider the variations:

n Ajmal Amir Kasab comes from the seething, desperate poverty of southern Punjab. This region has in recent years become fertile ground for jihadist recruitment.

n Faisal Shahzad had a privileged background, an American college degree, a white collar job (albeit not a great career record). Till the downturn of 2008, his was the classic American immigrant success story. In the period that followed, he discovered Islamism.

n David Coleman Headley was the quintessential misfit. Born of mixed parentage, he was the white man in Pakistan and the ‘half-Paki’ in the West, the boy from a conservative Muslim household who came to America to find his mother living with her boyfriend, who could never hold a steady job and was sucked into drug running. Jihad became his vengeance on the world.

All three men have very different histories. Those who insist on seeking a ‘root cause’ for terrorism have in the samples above not one but multiple root causes — poverty, economic recession, a broken home. Throw in Kashmir and Palestine, Iraq and anti-Americanism and the number of supposed triggers just grows. However, this ignores the elephant in the room: Pakistan.

Kasab’s example is typical — the poor boy recruited by the Lashkar-e-Toiba (some say sold by his father) and fed the fantasies of Islamist supremacism. Headley’s case is atypical — a Lashkar soldier who looked white, had an American passport and insider understanding of the US intelligence matrix.

Yet there is a third category. It consists of Faisal Shahzad; it consists of Omar Sheikh, the London School of Economics student who became a jihadist in Kashmir, a warrior for the Taliban, the killer of Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl. This is the ‘new typical’ — Jihad Joe, the educated, upper class Pakistani who seems just so regular.

Such a person is impossible to profile or identify. Yet, detection can come only after recognition of existence. Here, one is dealing with a country in complete denial. This is no more the case of a weak political establishment in Pakistan, or a hypocritical military brass that sees Islamism as an instrument of foreign policy but resists the mullah’s incursions domestically. Those pat explanations are obsolete.

In the period since 9/11, Pakistan’s reputation as export-house of terror and base for every form of Islamist passion, as a toxic entity that could theoretically contaminate any Muslim who touches it, has become absolute. This is difficult to accept for any middle-of-the-road Pakistani. Nevertheless, it is a verity staring people in the face.

When Omar Sheikh became infamous in the aftermath of Pearl’s brutal murder, General Pervez Musharraf blamed his jihad on Britain, pointing out he was educated in London and part of a radicalised British-Pakistani community. Likewise, the Pakistani foreign minister has smugly dismissed Shahzad as an American citizen who just happened to have Pakistani ancestors. In both cases, experience in the Islamist factories of Pakistan and indoctrination by religious and military leaders of the jihad located in Pakistan, and occasionally sent out to London and other cities to find new disciples, have been conveniently sidestepped.

The 800,000 strong British-Pakistanis have been regarded as the Western community most likely to produce suicide bombers. Intelligence officials in the West already talk of the “Pakistan-isation of Al Qaeda”. As a Heritage Foundation report emphasised in 2009, “Three quarters of the most serious terrorism cases investigated by British police have links to Al Qaeda in Pakistan.”

Some consider British jihad the misbegotten child of multiculturalism, a well-intentioned policy (complete with faith-based schooling) that unfortunately led to ghettoisation. The American integrative model was supposed to be superior. Even so, as the Shahzad episodes makes chillingly apparent, the jihadist impulse could catch up even very late in life.

Shahzad had obviously had a rough time professionally, having lost income and a home. This can be psychologically crippling. It took a few visits to the ‘homeland’ for it to be converted into religious hate. Easy availability of Islamist propaganda and smooth access to terror training centres — egalitarian institutions that accept a Kasab as easily as they do a Shahzad — has made Pakistan Islamism’s land of seduction. This is no more a functional nation-state. It is jihad’s Lebensraum.

Ashok Malik is an independent writer

![submenu-img]() 2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…

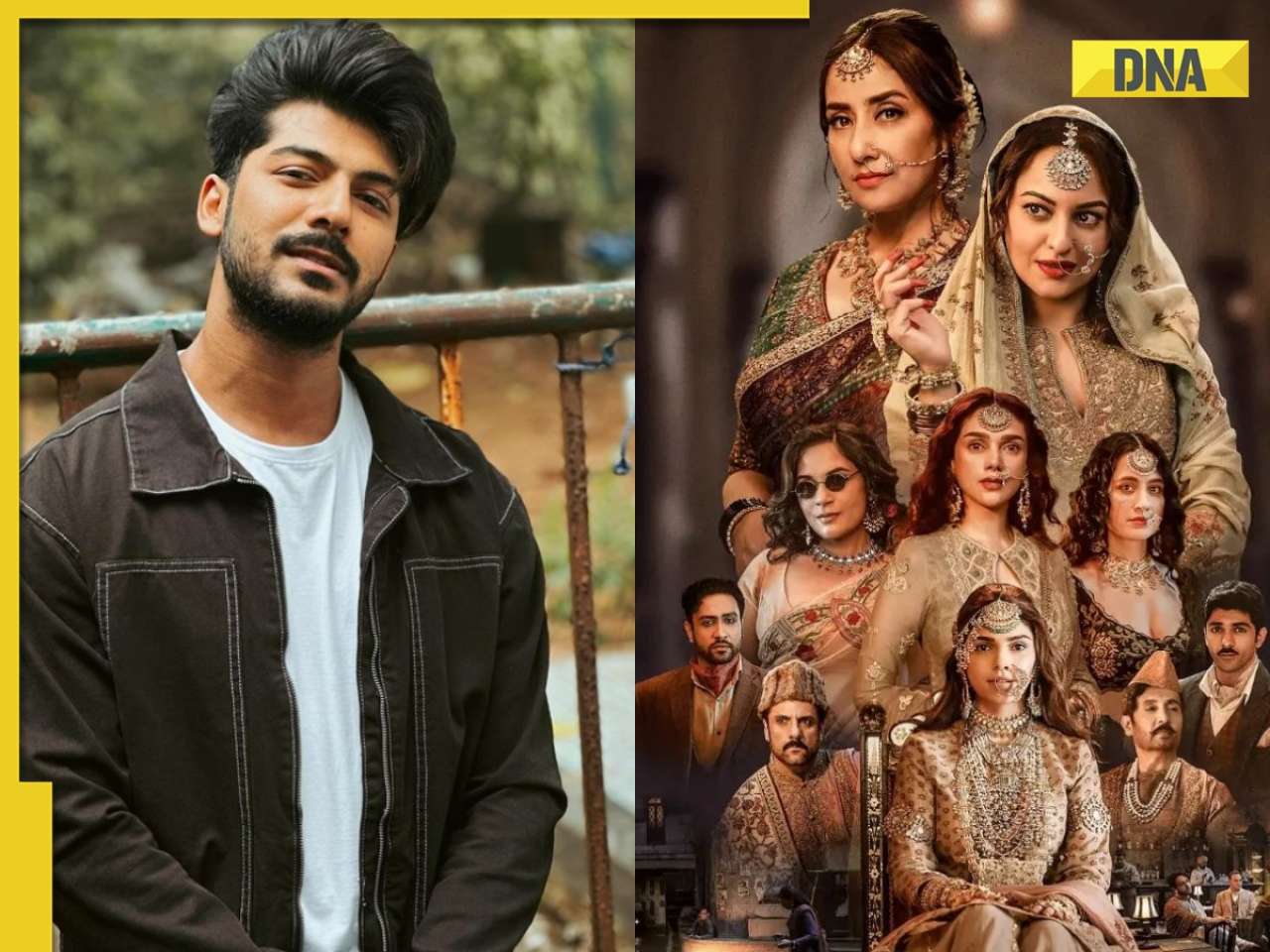

2024 Maruti Suzuki Swift officially teased ahead of launch, bookings open at price of Rs…![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…

Meet Jai Anmol, his father had net worth of over Rs 183000 crore, he is Mukesh Ambani’s…![submenu-img]() Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police

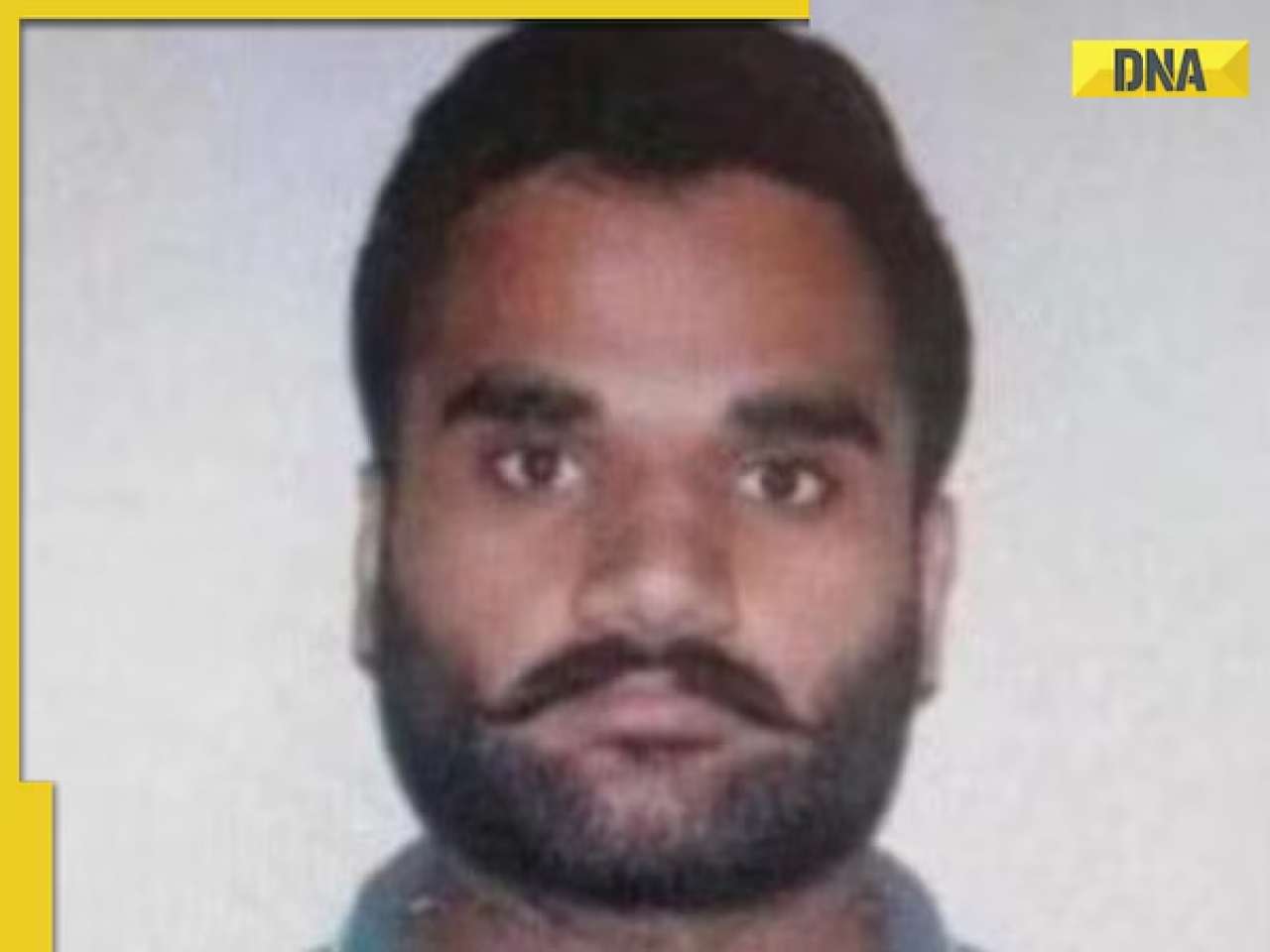

Shooting victim in California not gangster Goldy Brar, accused of Sidhu Moosewala’s murder, confirm US police![submenu-img]() Suspense continues over Rahul Gandhi, Priyanka Gandhi's candidatures from Raebareli and Amethi, final decision today

Suspense continues over Rahul Gandhi, Priyanka Gandhi's candidatures from Raebareli and Amethi, final decision today![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() 'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'

'Kyun bhai kyun?': Sheezan Khan slams actors in Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi, says 'nobody could...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..

Meet actress who once competed with Aishwarya Rai on her mother's insistence, became single mother at 24, she is now..![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’

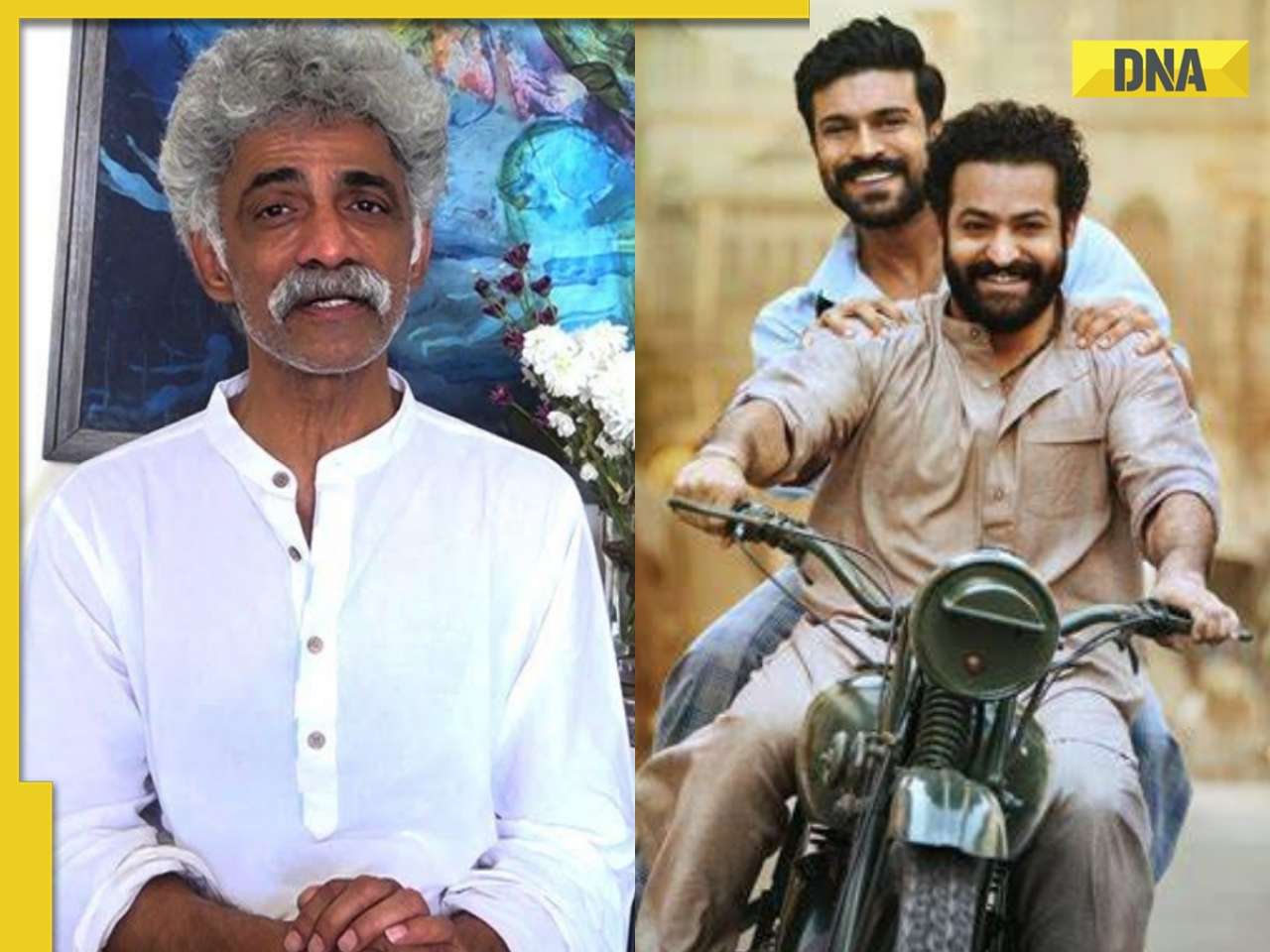

Makarand Deshpande says his scenes were cut in SS Rajamouli’s RRR: ‘It became difficult for…’![submenu-img]() Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...

Meet 70s' most daring actress, who created controversy with nude scenes, was rumoured to be dating Ratan Tata, is now...![submenu-img]() Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore

Meet superstar’s sister, who debuted at 57, worked with SRK, Akshay, Ajay Devgn; her films earned over Rs 1600 crore![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets

IPL 2024: Spinners dominate as Punjab Kings beat Chennai Super Kings by 7 wickets![submenu-img]() Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here

Australia T20 World Cup 2024 squad: Mitchell Marsh named captain, Steve Smith misses out, check full list here![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals

SRH vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch

Viral video: Man's 'peek-a-boo' moment with tiger sends shockwaves online, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch

Viral video: Desi woman's sizzling dance to Jacqueline Fernandez’s ‘Yimmy Yimmy’ burns internet, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts

Viral video: Men turn car into mobile swimming pool, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet

Meet Youtuber Dhruv Rathee's wife Julie, know viral claims about her and how did the two meet![submenu-img]() Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

Viral video of baby gorilla throwing tantrum in front of mother will cure your midweek blues, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)