This is the Age of Scepticism. How much of what one reads and hears is one to believe? Can sportsmen really hide or distort the truth behind nicely-worded autobiographies penned by named ‘ghosts’? Shoaib Akhtar’s much-publicised autobiography Controversially Yours (with Anshu Dogra, Harper Sport, 2011, price: Rs 499) gives rise to such thoughts.

First off, this is an extremely readable account of the life of a paceman who rose from penury and virtual illiteracy to a position where, for some years he was regarded as the fastest bowler in the world, self-taught himself to speak the English language, to live the high life and to hold his own in any company, however exalted.

The book is an engrossing read, thanks as much to Anshu Dogra’s ability to tell a story — or as Shoaib himself puts it, “ for giving me the words” — as to Akhtar’s colourful and varied life experiences, where his “in your face” attitude invariably landed him into trouble, not always of his own making.

Page after page of the Shoaib story glows with his professed love for things Indian. His dearest friend, Sudesh Rajput is from Delhi. He loves Indian crowds and fans: “I have discovered over the years that Indian cricket fans are warm and generous and know their cricket. As a result, I love playing and touring in India...... I have really been touched by the Indian crowd....”; he admires the cricket set-up in India; he is a great fan of Salman Khan and Bollywood movies: “.... Salman is straight after my heart, he is generous, likes to help people, is a straight talking guy.....”.

He praises the two contemporary giants of Indian cricket, Tendulkar and Dravid but criticises their earlier approach, believing that they were not aggressive enough and not match-winners. In this, he is wrong, for figures prove the contrary. But as a great votary of the constitutional right of ‘free speech’ once said, “He is completely wrong in what he says, but I will defend to my last breath his right to say it”.

Shoaib believes that the induction of aggressive players like Sehwag, Yuvraj, Gambhir and Kohli, benefited the two great older stalwarts. Tendulkar, he believes, is “more at ease” now, where earlier “the poor man carried the entire burden on his shoulders”. Dravid, he writes, “has a great technique” (how perceptive, Mr Akhtar) “but has never been a match-winner” (wrong again, Mr. Akhtar!).

He also makes an unwarranted remark about Tendulkar, then handicapped with a tennis-elbow, “walking away from” a particularly fast ball which “he didn’t even touch” in a match at Faisalabad. If the comment was meant to convey that Tendulkar was “running away”, it is so utterly incredible that it can only be described as an untruth, a lie. More likely — in this Age of Scepticism — it’s a throw-away line, intended to boost sales?

Yet, despite an occasional demonstrable untruth, strangely, Shoaib comes across on the whole, as an honest, shooting straight-from-the-shoulder, god-fearing, loyal, brash young man. There is something almost childishly naive in his early self-belief that he would become a great cricketer one day, with a touch of emotional ‘teary-eyedness’ in his friendship with Aziz Khan, the tongawala outside Lahore Railway Station.

Akhtar, penniless and forlorn, sought some food and help from the tongawala. “He looked at me and said, ‘tu hai kaun?’ (Who are you?) I remember him smiling and asking why he should oblige me. Because when I joined the Pakistan team one day, I would come back to meet him, I said. In this manner, I managed to convince Aziz Khan, the tongawala, to share his bedding and sleeping space with us, and that night we slept peacefully on a footpath in Lahore”.

Shoaib kept his promise, when he returned from his debut series in India in 1999.

Though now famous and in an elite league, “I headed towards the railway station to look for Aziz Khan, the tongawala who had given me shelter six years ago.”

An emotional re-union took place. The crowd gathered around them. Aziz Khan pointed to them and said, “Look how many people recognise you and are dying to take you to their homes now”. I said: “Yes, but you were the one who gave me shelter when I was unknown, so I recognise you alone and am here to meet only you”.

His everlasting regret is that he did not play in the Imran era. He hero-worships Imran: “The Pakistan team is mostly made up of players who have come from economically challenged backgrounds and have been deprived of an education. So we learn everything from cricket; it is our educational institution. We learn to speak English, drive cars and conduct ourselves. Therefore, we are very vulnerable and need good, strong mentors to protect us and take us in the right direction. Somebody like Imran khan, for instance, who in my opinion has been our greatest captain. He was a fabulous bowler and all rounder who nurtured talent.... was selfless and hardworking and was an example to all of us.”

Almost everyone and everything else in Pakistan cricket earns a caustic tongue lashing. The PCB and its various Chairmen: “uncaring, incompetent and self-obsessed guys” (except Khalid Mahmood and Tauqir Zia); the captains he played under, (except Amir Sohail), the worst being reserved for Shoaib Malik: “a ghulam, a slave who would jump through hoops for them”; his coaches, especially Intikhab Alam and Wasim Raja. Sample this: “In general, our coaches have had nothing to offer, apart from playing dirty politics. They just want to earn some money and travel in their old age — bas! Take Intikhab Alam: he is the most illiterate man you could meet. He has no clue what coaching is all about and can’t distinguish an in-swinger from an out-swinger, but he gives us advice!”. Strong words.

In the absence of any organised training, Shoaib kept fit in the only way he knew: he just kept running, like a loony, he ran everywhere. In the process, he damaged his knees badly. That partly accounted for the fact that he played only 46 Tests and 163 one-day games over 18 years at the top. (Some of his managers, coaches and colleagues thought he consistently ‘faked’ injuries; Shoaib presents a convincing case to the contrary).

Pakistan cricket has always struck one as being complex. This book reveals just how complex. Consider this scenario, as painted by Akhtar, of his first day with the Test team: “The atmosphere in the dressing room was horrible; the rest of the team ganged up against me and made things as uncomfortable as they possibly could, peppering every phrase aimed at me with abuses. The result was that I felt messed up and terribly unsure of myself. The first time I walked into the Pakistan dressing room, I was stunned by the reception I got. The atmosphere was vicious and almost every senior player, when not yelling at me and other juniors, was either whining about how they were being ill-treated by the management or swearing at them....”

Akhtar’s take on match-fixing also makes for interesting reading. Nobody ever pointed a finger at him. In fact, he and Afridi were the known ‘clean’ Pakistani players. Just how widespread this evil has become is evident from his observation that “everyone seems to be involved”. Akhtar blames the PCB in this regard for not creating a proper environment in which these youngsters, most of them from shockingly poor backgrounds (like Akhtar himself), are mentored and taught how to resist the approaches from agents, some of whom are named in the book.

There is a fascinating chapter on the last England tour when a newspaper ‘sting’ broke the story of ‘spot-fixing’ which, ultimately led to the banning and criminal conviction of three of his teammates.

Here is Shoaib on the youngest of the lot, Mohammed Aamer: “Some time back, I talked to Aamer about the life that awaited him. He was the youngster earmarked for the change of guard, to take over from me. He was juggling three phones in his hand and was swinging a set of ear-phones around. I told him, be careful, stop staring at the big tree, you will lose the view of the jungle. I sensed that he was getting into bad company and told him not to shift to Lahore, for it’s a party house for cricketers and can be very distracting. I told him not to do what I had done, or he would suffer. He didn’t listen to me.”

Akhtar’s economic circumstances at the start of his career and for a large part of it, as well, made him a prime target for match-fixers. He resisted all such attempts, thankfully, and never lost his ‘clean’ image. For that alone, the cricket world has much to thank him, and perhaps, overlook all his trespasses. It is a sign of the times in which we live that we honour ‘honest cricketers’ — much like the irony of being thankful for Judges with integrity — isn’t that a “given”, as they say these days?

—Fredun E De Vitre has been a cricket commentator and columnist for the past four decades. He is also the author of the book ‘Willow Tales — the Lighter Side of Indian Cricket’. His present professional involvement as a lawyer has not diminished his passion for the game of cricket

![submenu-img]() This film made Dharmendra star, was originally offered to Sunil Dutt, actor suffered near-death injury, movie earned...

This film made Dharmendra star, was originally offered to Sunil Dutt, actor suffered near-death injury, movie earned...![submenu-img]() Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic Scam (Tested For 90 Days) Does This Blue Tonic Supplement Work For Weight Loss?

Sumatra Slim Belly Tonic Scam (Tested For 90 Days) Does This Blue Tonic Supplement Work For Weight Loss?![submenu-img]() Sugar Defender Scam (60 Days Of Testing) What Users Are Saying About This Blood Sugar Support Formula

Sugar Defender Scam (60 Days Of Testing) What Users Are Saying About This Blood Sugar Support Formula![submenu-img]() FitSpresso Scam (I've Used It For 180 Days) Are These Weight Loss Pills Effective?

FitSpresso Scam (I've Used It For 180 Days) Are These Weight Loss Pills Effective?![submenu-img]() Understanding Legal Entity Identifiers: The Advantages and Benefits

Understanding Legal Entity Identifiers: The Advantages and Benefits![submenu-img]() Meet man who almost failed in class 12, IIT alumnus, who quit high-paying job at Infosys for UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet man who almost failed in class 12, IIT alumnus, who quit high-paying job at Infosys for UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meghalaya Board 10th, 12th Result 2024: MBOSE SSLC, HSSLC Arts results to be declared on this date

Meghalaya Board 10th, 12th Result 2024: MBOSE SSLC, HSSLC Arts results to be declared on this date![submenu-img]() Campus placement: Over 7700 students of IIT 2024 batch yet to get jobs, finds RTI

Campus placement: Over 7700 students of IIT 2024 batch yet to get jobs, finds RTI![submenu-img]() IIT-JEE topper joins IIT Bombay with AIR 1, skips placement drive, now working as a...

IIT-JEE topper joins IIT Bombay with AIR 1, skips placement drive, now working as a...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate builds Rs 1057990000000 company, leaves to get a job, now working as a….

IIT graduate builds Rs 1057990000000 company, leaves to get a job, now working as a….![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() AI models set goals for pool parties in sizzling bikinis this summer

AI models set goals for pool parties in sizzling bikinis this summer![submenu-img]() In pics: Aditi Rao Hydari being 'pocket full of sunshine' at Cannes in floral dress, fans call her 'born aesthetic'

In pics: Aditi Rao Hydari being 'pocket full of sunshine' at Cannes in floral dress, fans call her 'born aesthetic'![submenu-img]() Jacqueliene Fernandez is all smiles in white shimmery bodycon at Cannes 2024, fans call her 'real Barbie'

Jacqueliene Fernandez is all smiles in white shimmery bodycon at Cannes 2024, fans call her 'real Barbie'![submenu-img]() AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer

AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer![submenu-img]() Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet

Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() This film made Dharmendra star, was originally offered to Sunil Dutt, actor suffered near-death injury, movie earned...

This film made Dharmendra star, was originally offered to Sunil Dutt, actor suffered near-death injury, movie earned...![submenu-img]() Sanjay Leela Bhansali breaks silence on Sharmin Segal's performance in Heeramandi: She kept saying, 'Mama, I will...'

Sanjay Leela Bhansali breaks silence on Sharmin Segal's performance in Heeramandi: She kept saying, 'Mama, I will...'![submenu-img]() 'To my surprise...': Neena Gupta says she is amazed as everyone from different backgrounds loves Panchayat

'To my surprise...': Neena Gupta says she is amazed as everyone from different backgrounds loves Panchayat![submenu-img]() Worst Indian film ever ended actor's career, saw court cases; it's not Jaani Dushman, Adipurush, RGV Ki Aag, Himmatwala

Worst Indian film ever ended actor's career, saw court cases; it's not Jaani Dushman, Adipurush, RGV Ki Aag, Himmatwala![submenu-img]() Meet director, was thrown out of film for advising Salman Khan, gave flops; later made 6 actors stars with just one film

Meet director, was thrown out of film for advising Salman Khan, gave flops; later made 6 actors stars with just one film![submenu-img]() Old video resurfaces: Hippo attempts zoo breakout, gets slapped by security guard

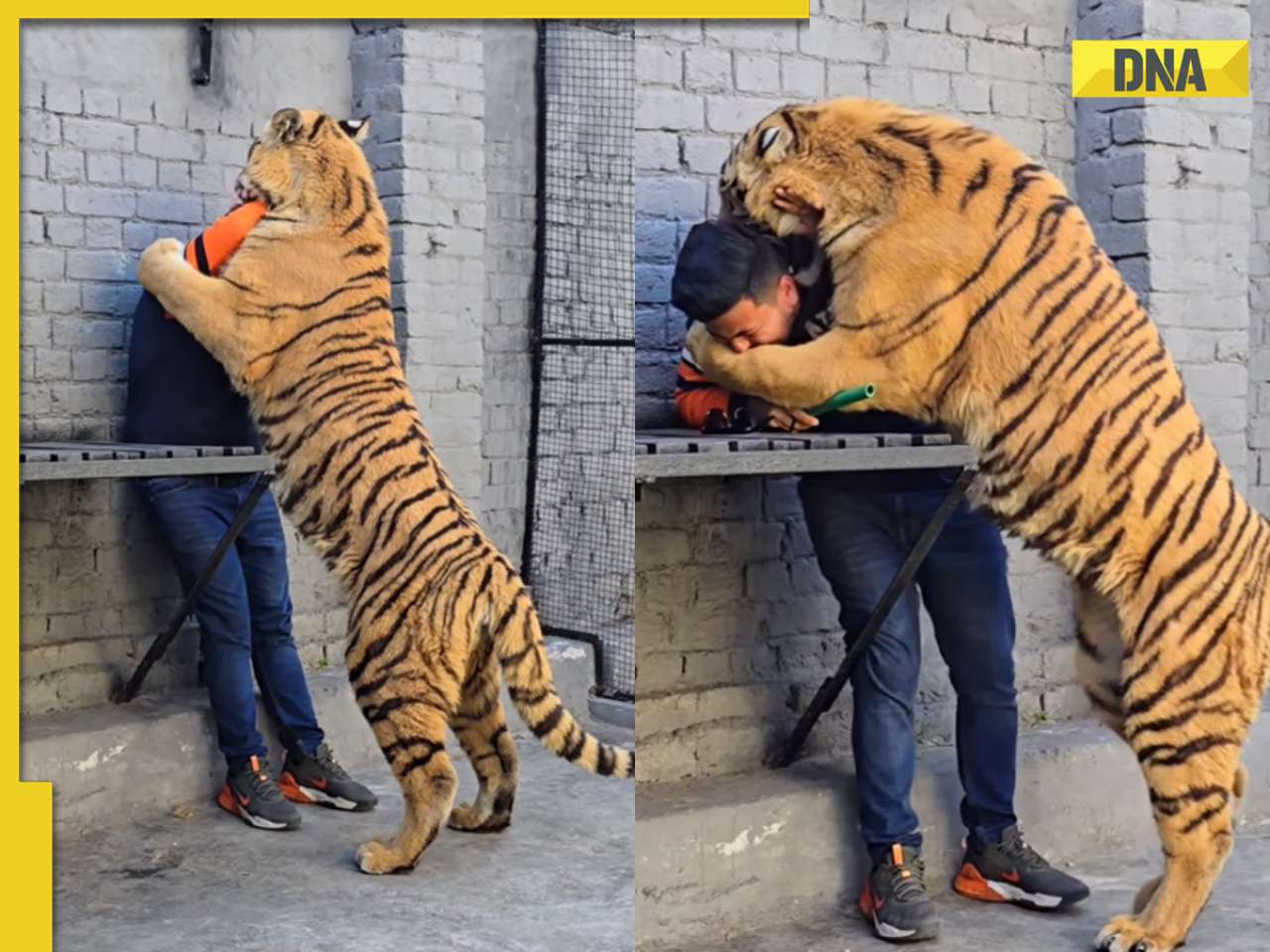

Old video resurfaces: Hippo attempts zoo breakout, gets slapped by security guard![submenu-img]() Mysterious pillars of light in sky spark alien speculation, know what they are

Mysterious pillars of light in sky spark alien speculation, know what they are![submenu-img]() Shaadi.com's innovative dowry calculator garners social media praise, here's why

Shaadi.com's innovative dowry calculator garners social media praise, here's why![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman gracefully grooves to Aditi Rao Hydari’s Saiyaan Hatto Jaao from Heeramandi, watch

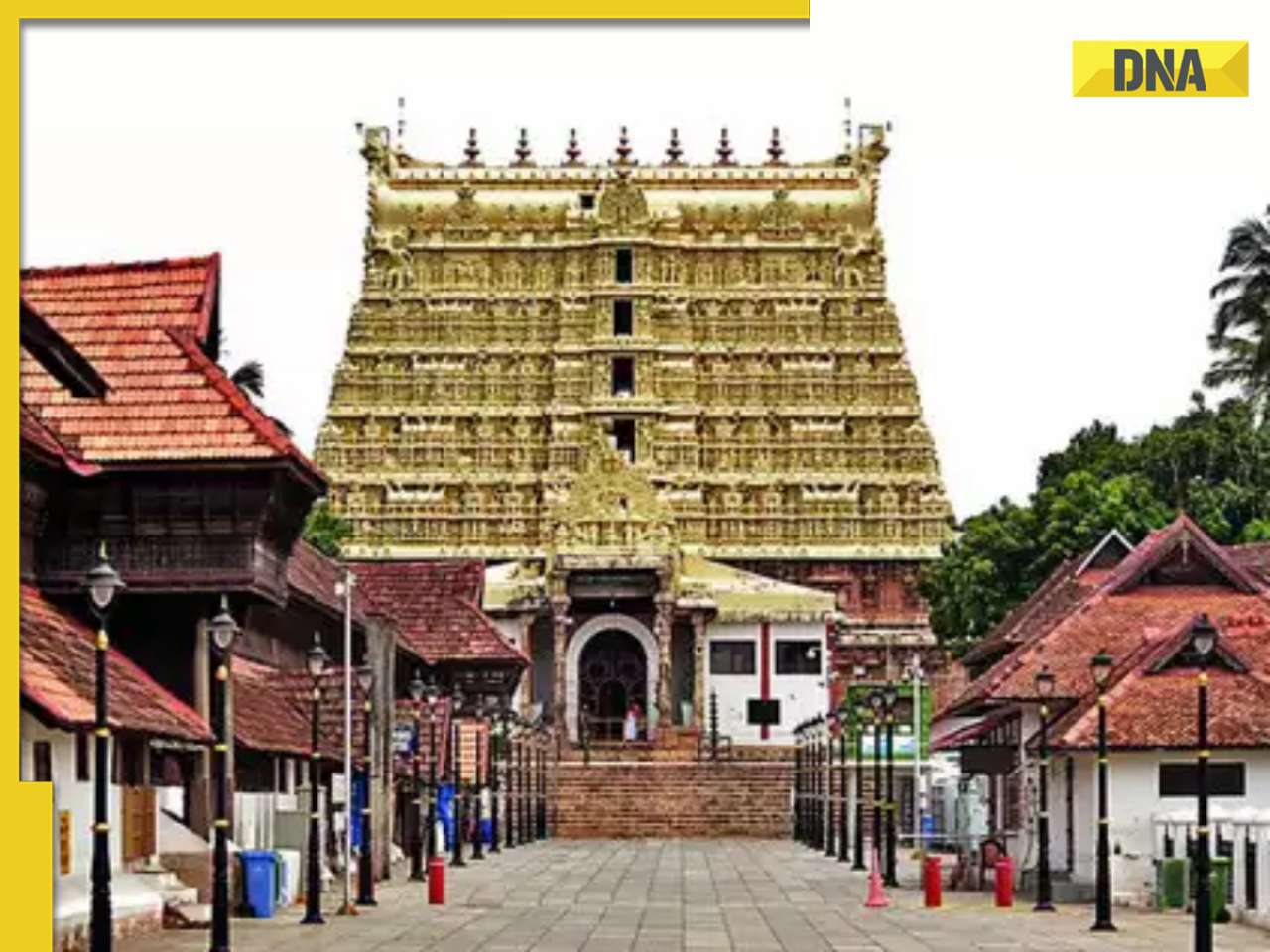

Viral video: Woman gracefully grooves to Aditi Rao Hydari’s Saiyaan Hatto Jaao from Heeramandi, watch![submenu-img]() Know about Travancore royal family that controls treasure of the wealthiest temple on Earth

Know about Travancore royal family that controls treasure of the wealthiest temple on Earth

)

)

)

)

)

)