Similar social upsrisings have floored leaders from North Africa and the Middle East but China's leaders, and the country itself, are made of sterner stuff.

Like battle-hardened boxers, China's Communist Party leaders are leaning back on the ropes, patiently absorbing the blows from angry village protesters who have grabbed headlines but lack a knockout punch.

Similar social upsrisings have floored leaders from North Africa and the Middle East but China's leaders, and the country itself, are made of sterner stuff.

Analysts say it would take an unlikely combination of blows for any semblance of an Arab Spring to take root in China: collapse of the economy, a breakdown of the Party system, a comprehensive loss of trust in the central government, and a cohesive anti-party movement in rural and urban areas.

Still, China has endured headlines that would make many an Arab leader tremble.

Villagers in Wukan in south China chase off local officials and barricade themselves in for a 10-day standoff. Thousands march in Haimen city less than 160 km (100 miles )away to protest against a power plant project. Workers stage a sit-in in Dongguan city to the west, demanding backpay after their paper plant closed down.

But while Arab Spring protesters have scored knockout blows this year, economic conditions appear to have China on course for a comfortable points decision.

After the wave of Arab Spring revolutions, analysts began looking for markers that might be useful for predicting the next uprising. The most common characteristics included a disproportionately large segment of the population aged under 25, stagnating GDP per capita, and widening income inequality.

China doesn't stand out in any of those categories. The one-child policy means the country is aging rapidly, and the bigger worry is potential shortages of young workers. GDP per capita is rising steadily. Income inequality, although wide, may narrow as Beijing mandates large minimum wage increases.

Some 80 million Communist Party members and millions more who have benefited from China's economic boom have little interest in spreading social unrest that would undermine those gains. Among China's vast bureaucracy, where college graduates are competing for jobs, and the People's Liberation Army, appetite for change is even lower.

"With civil servants and military, with their support, even when there is extensive discontent among the general public, the regime can still maintain its rule for quite a long period of time," said Kin-man Chan, associate professor at the department of sociology at Chinese University of Hong Kong.

SPARK WON'T START A PRAIRIE FIRE

Other factors favour the Party over the protesters, who lack central organisation.

These include strong political cohesion, a system that reinforces support for the central government over local officials, a massive police force and fairly tight controls on traditional and social media.

The last time the Politburo Standing Committee was seriously split was in 1989, a divide that gave time for the democracy movement centred on Tiananmen Square to snowball. Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping eventually stepped in, Party secretary Zhao Ziyang was sacked, and the movement was crushed on June 4 that year in a bloody military crackdown that killed hundreds, perhaps thousands.

The Chinese government's fear is that, in the more distant future, those trends could gather momentum and threaten it.

"I don't think this can become a single spark that starts a prairie fire," said Ting Wai, a professor of political science at Hong Kong Baptist University, referring to Mao Zedong's famous thesis from the Chinese revolution.

"There are many incidents of social unrest like these in China, but I don't think in the near future they will join together," Ting said.

TRICKLE, NOT A FLOOD

While pressures from riots, strikes and other mass incidents could chip at the Party's grip on the country, analysts say that weakening remains manageable, a trickle rather than a flood.

Even the incident in the rebellious Guangdong province village of Wukan, where concessions to end the standoff appeared particularly favorable, only rippled the surface.

Liu Feiyue, a human rights advocate in central China's Hubei province who collects reports from protesters, said "the scope of concessions in Wukan was unusually large, especially on freeing detained villagers and a fresh village election".

"This showed unusual flexibility and reasonableness from the Guangdong government," said Liu, who runs the Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch website.

"But I don't think the Wukan model will spread nationwide easily. There's too much conservatism and fear of change, and other places tend to offer only tactical compromises and then officials return to high-pressure methods and to settling scores," Liu said in a telephone interview.

The Communist Party has years of experience handling incidents of mass unrest that have grown in number as economic reforms gathered pace in the 1990s and 2000s, bringing booming growth and rising incomes but also spawning a widening wealth gap and uneven development.

Each day, authorities grapple with nearly 250 mass incidents, the euphemism for riots and protests, somewhere across the country, based on the annual figure of more than 90,000 incidents that Chinese experts estimate occur annually.

It has also been going on for years -- in 2004 there were 78,000 incidents and Hu's predecessor Jiang Zemin had to defuse huge strikes as he and Premier Zhu Rongji overhauled lumbering state enterprises, shattered the iron rice bowl and laid off thousands of workers from once guaranteed jobs.

While incidents differ, China's approach to handling violent protest has been fairly formulaic. First, security forces quell the incident with overwhelming force and arrest the ringleaders. The authorities one rung up the ladder at the county or province often then address the source of the outrage -- closing down the polluting factory, arresting the corrupt local official, or ordering the backwages paid.

"THROW THE BUMS OUT"

There is little sign of discord in the Politburo when it comes to social stability, particularly with a leadership transition coming.

Zhou Yongkang, the Standing Committee member in charge of public security, was not speaking just for himself in a speech carried in newspapers on Thursday that urged law-and-order cadres to ensure "a harmonious and stable social setting" ahead of the Communist Party's 18th Congress in late 2012.

Social media are yoked as well. China has banned Facebook and Twitter and while Weibo, the popular microblogging site, has become a source for news to spread, tight controls -- posts are deleted or topic searches are banned -- hinder the ability to use it to organise, Chan said.

Activists who travel to areas of unrest to support or organise them are arrested. Such incidents are geographically widespread and often in remote areas.

China's central government also benefits from wide respect at the local level. Unlike the United States, where voters re-elect their local officials but want to "throw the bums out" in Washington, China's central government enjoys relative popularity in relation to local village or county leaders.

Indeed, the provincial delegation sent by provincial Party Chief and Politburo member Wang Yang to negotiate in Wukan was welcomed warmly. When a deal to end the standoff was reached, the village elders told the rest of the village to take down their banners and go home.

This respect for high leadership is perhaps reinforced by a tradition of seeking redress from on high through petitioning the emperor's officials.

Thirty years of strong economic growth have added credibility for China's Communist rulers, who enjoy a higher level of trust than their Arab counterparts, Chinese University's Chan added.

"Because of this trust, basically the stability of China can still be maintained," Chan said.

There was some risk people could be disillusioned if the government failed to address their petitions positively. "But now at this moment I don't think that China has reached what has happened in Egypt," Chan added.

Wukan was arguably closer to anything resembling an Arab-style movement that China has seen for a while. They tossed out their local leaders, installed their own rebel village leadership and manned barricades against police in open revolt for 10 days.

But even in Wukan, the contradictions were apparent, illustrating the gulf between China and turmoil abroad.

"Democracy is good for citizens, as citizens can make decisions for themselves," said Yang Semao, a village representative in Wukan, adding that calls for democracy and elections would be "better if they spread nationwide".

But he added: "China won't turn out to be as serious as the other countries, as long as the Chinese Communist Party is in control."

![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani’s firm launches new brand, Reliance’s Rs 8200000000000 company to…

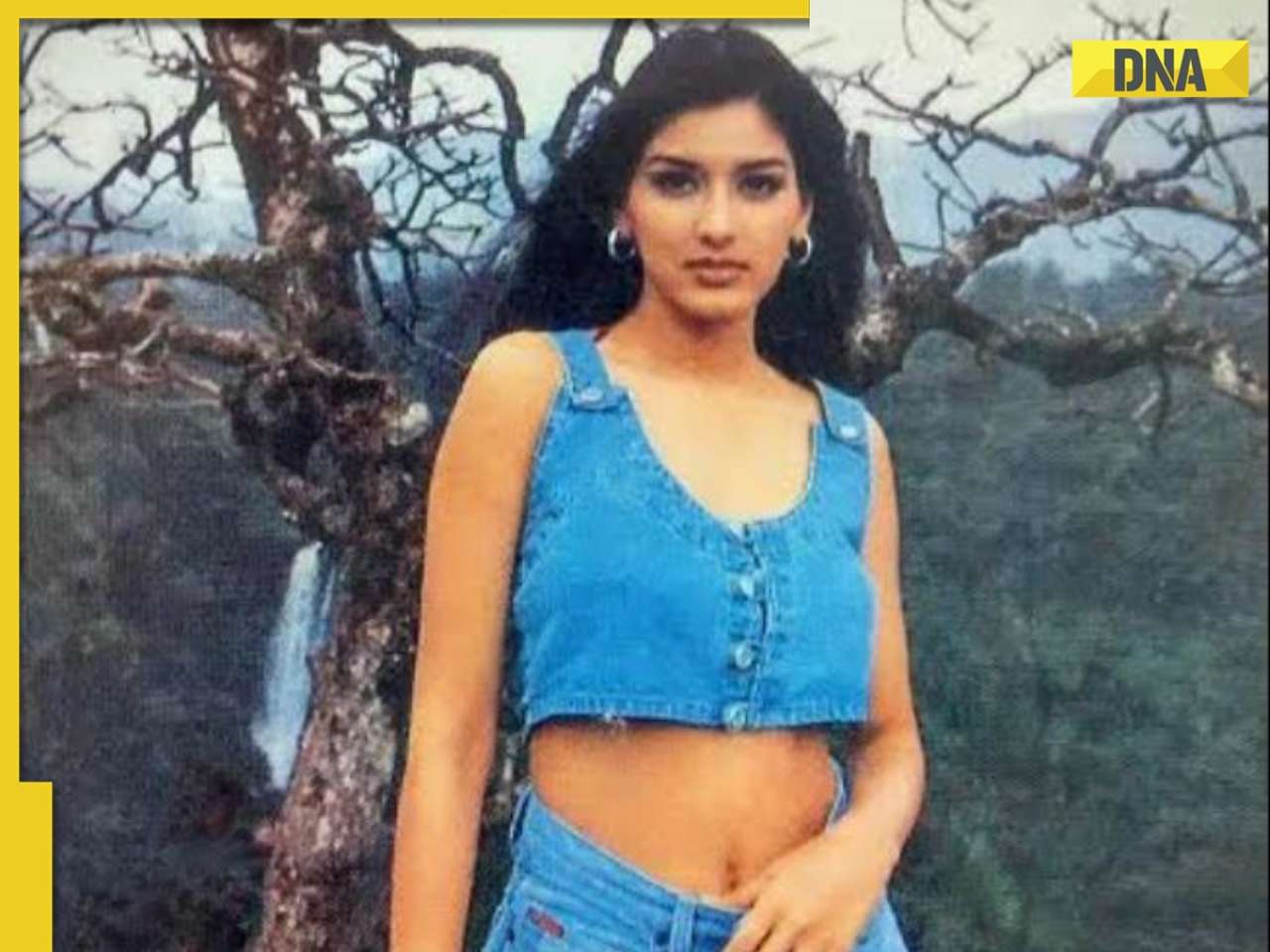

Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani’s firm launches new brand, Reliance’s Rs 8200000000000 company to…![submenu-img]() Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'

Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'![submenu-img]() Heavy rains in UAE again: Dubai flights cancelled, schools and offices shut

Heavy rains in UAE again: Dubai flights cancelled, schools and offices shut![submenu-img]() When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid

When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid![submenu-img]() Gautam Adani’s firm gets Rs 33350000000 from five banks, to use money for…

Gautam Adani’s firm gets Rs 33350000000 from five banks, to use money for…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'

Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'![submenu-img]() When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid

When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid![submenu-img]() Salman Khan house firing case: Family of deceased accused claims police 'murdered' him, says ‘He was not the kind…’

Salman Khan house firing case: Family of deceased accused claims police 'murdered' him, says ‘He was not the kind…’![submenu-img]() Meet actor banned by entire Bollywood, was sent to jail for years, fought cancer, earned Rs 3000 crore on comeback

Meet actor banned by entire Bollywood, was sent to jail for years, fought cancer, earned Rs 3000 crore on comeback ![submenu-img]() Karan Johar wants to ‘disinherit’ son Yash after his ‘you don’t deserve anything’ remark: ‘Roohi will…’

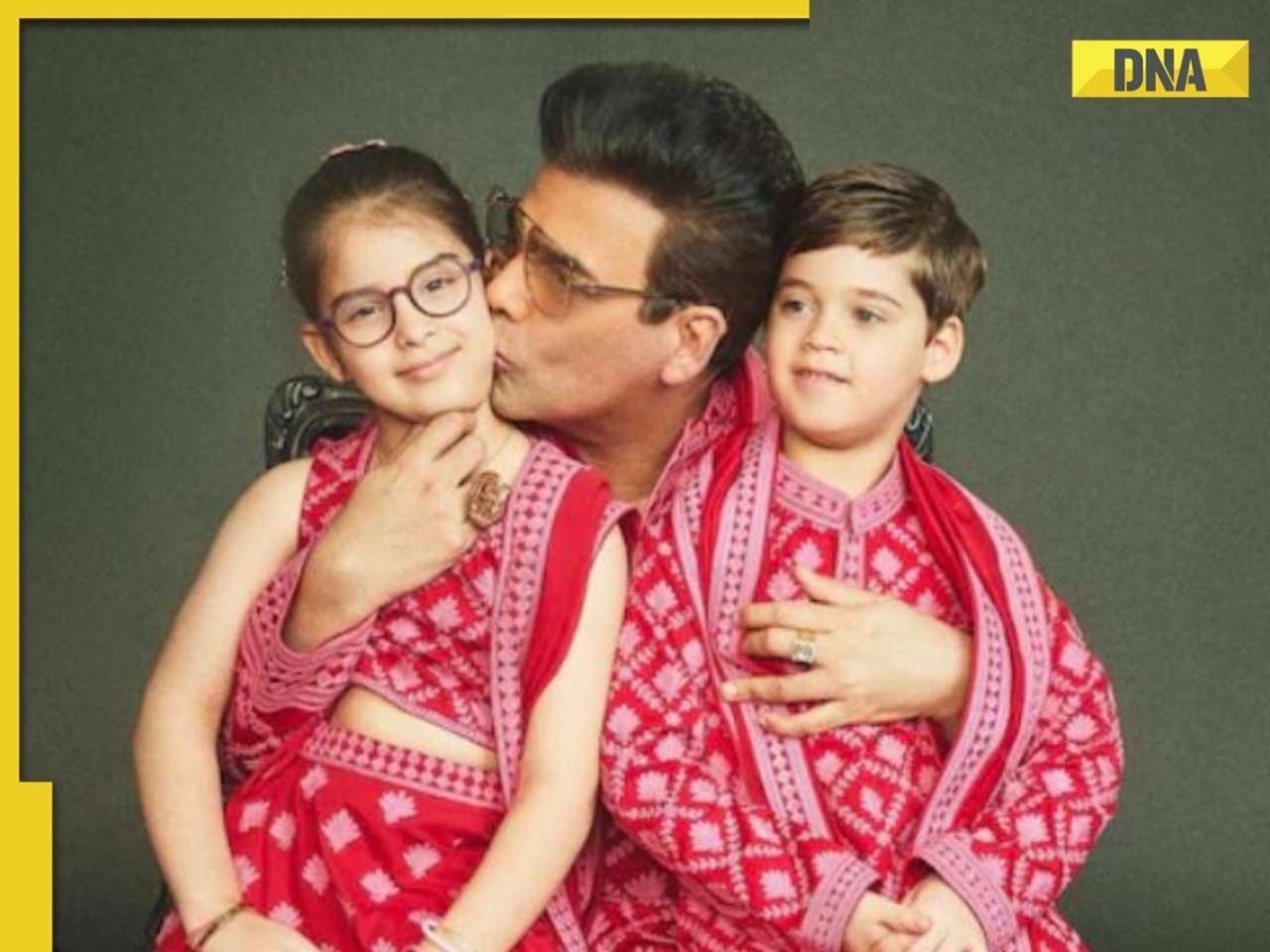

Karan Johar wants to ‘disinherit’ son Yash after his ‘you don’t deserve anything’ remark: ‘Roohi will…’![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Bhuvneshwar Kumar's last ball wicket power SRH to 1-run win against RR

IPL 2024: Bhuvneshwar Kumar's last ball wicket power SRH to 1-run win against RR![submenu-img]() BCCI reacts to Rinku Singh’s exclusion from India T20 World Cup 2024 squad, says ‘he has done…’

BCCI reacts to Rinku Singh’s exclusion from India T20 World Cup 2024 squad, says ‘he has done…’![submenu-img]() MI vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

MI vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB and MI still qualify for playoffs?

IPL 2024: How can RCB and MI still qualify for playoffs?![submenu-img]() MI vs KKR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders

MI vs KKR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders ![submenu-img]() '25 virgin girls' are part of Kim Jong un's 'pleasure squad', some for sex, some for dancing, some for...

'25 virgin girls' are part of Kim Jong un's 'pleasure squad', some for sex, some for dancing, some for...![submenu-img]() Man dances with horse carrying groom in viral video, internet loves it

Man dances with horse carrying groom in viral video, internet loves it ![submenu-img]() Viral video: 78-year-old man's heartwarming surprise for wife sparks tears of joy

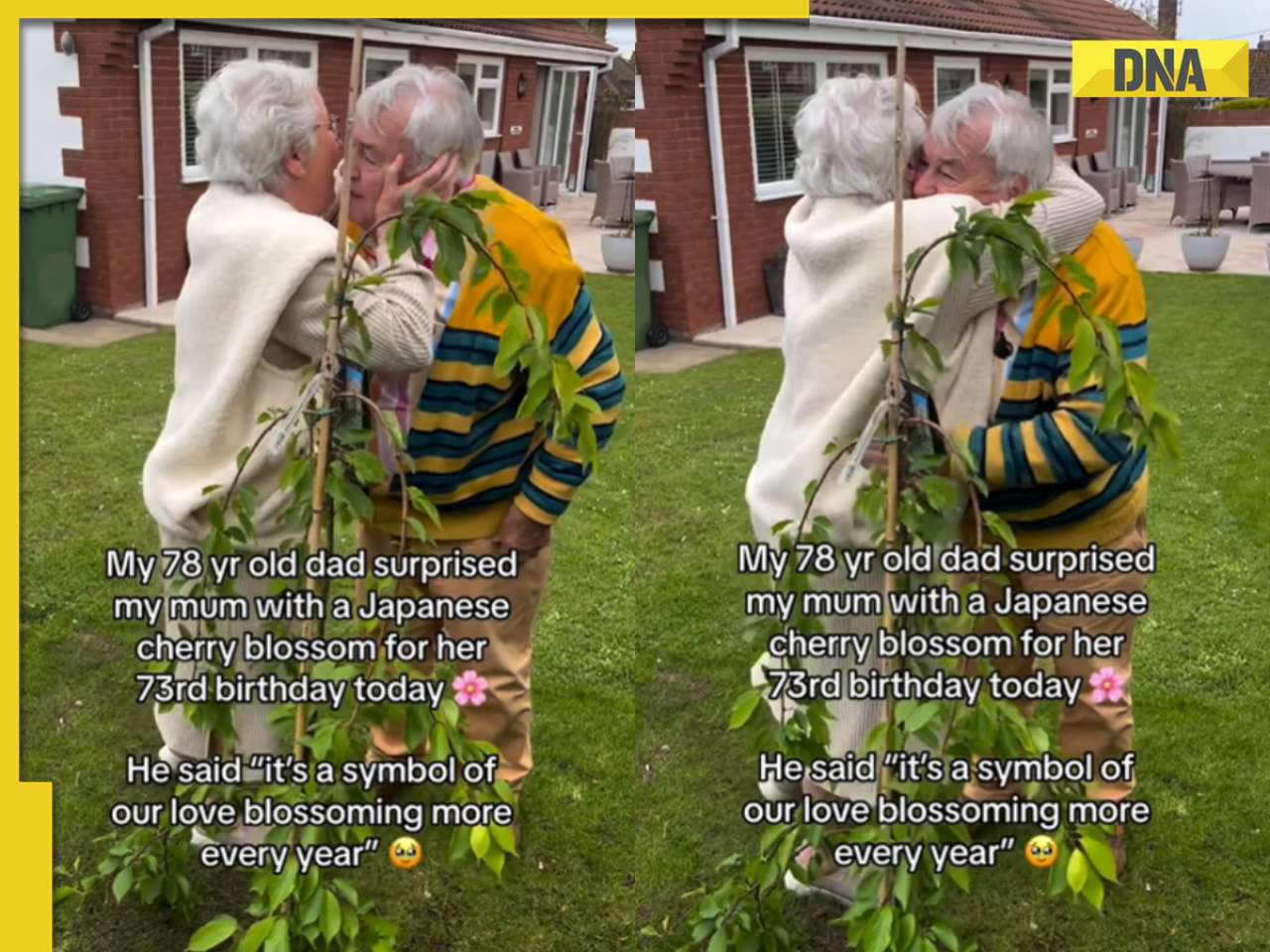

Viral video: 78-year-old man's heartwarming surprise for wife sparks tears of joy![submenu-img]() Man offers water to thirsty camel in scorching desert, viral video wins hearts

Man offers water to thirsty camel in scorching desert, viral video wins hearts![submenu-img]() Pakistani groom gifts framed picture of former PM Imran Khan to bride, her reaction is now a viral video

Pakistani groom gifts framed picture of former PM Imran Khan to bride, her reaction is now a viral video

)

)

)

)

)

)