This village in a remote corner of the world’s biggest democracy does not believe in elections: it prefers consensus. The results: an all-women panchayat.

This village in a remote corner of the world’s biggest democracy does not believe in elections: it prefers consensus. The results: an all-women panchayat, Dalits and Muslims living cheek-by-jowl with upper caste Hindus, and progressive farming in a suicide-prone region.Make no mistake with the spelling. “No, not Godhra, this is Gordha,” repeats the wrinkle-faced farm labourer wearing a clean Gandhi-cap and white kurta. Since its formation in 1966, this village of 800 people never elected its sarpanch even once; it selects its head consensually, by what its veterans call “ekmat”. “We choose our sarpanch in five minutes,” says Tulsiram Laxman Thorat, a septuagenarian landless Dalit from Gordha.

There’s no particular reason for electing their sarpanch unopposed. Way back, Pandhari Tohare, a respected veteran, had to honour the villagers’ decision to anoint him as the first sarpanch. Tohare is no more, but his legacy lives on. In the assembly and parliamentary elections, each villager is free to vote for any party or candidate as per his wisdom, villagers say.

About 60 km from Akola in the district’s Telhara block, in western Vidarbha’s suicide-ravaged belt, Gordha is living Mahatma Gandhi’s vision: “A consensus-seeking democracy is a more mature system of government.” As ardent Gandhians say, consensus is quintessentially persuasive; elections are necessarily coercive.

Gandhi believed nature was fundamentally cooperative, not competitive. Things cooperated with one another for the good of the one whole.

It is Gordha’s character of cooperation that has scripted the transformation in the village. What strikes you first is the cleanliness, spacious roads, well-marked houses with enough frontage and backyard, and solar street lamps. Each house has a nameplate bearing the names of husband and wife as joint owners.

This one’s a different world. They follow their castes and religions, yes, but they don’t discriminate or hate each other. Muslims join Hindus in the Ganesh festival; Hindus join Muslims in Eid. There are no separate colonies for Dalits, tribals and OBCs. A Deshmukh has a scheduled caste or a Muslim in his neighbourhood. There’s no place for divisive politics. There is politics, if you want, but it’s of the consensual kind. Villagers take decisions after consultations.

In 2005, when the post of sarpanch got reserved for women, an all-women panchayat came into being. The villagers decided there should be members from the SC and Muslim communities as well - though there was no reservation at play here - besides OBCs and Marathas.

“We decided on having an all-women panchayat with representation from all castes and religions,” says the present sarpanch, Shalinitai

Deshmukh. Her ailing husband, Ganesh Deshmukh, a former sarpanch, is the man largely credited with the Gordha transformation.

Villagers insist Shalinitai was selected not because she is a Maratha, but because she had qualities. “She is strong, articulate and loving,” says Devkabai Hatekar, 60, a Dalit farm labourer. “The village you see today is all her hard work.”

Evidently, the decision to have an all-women panchayat has paid off. First, the women members brought cleanliness, which has reduced health problems. They also banned liquor and open defecation.

Secondly, the village invested in water supply schemes to ensure that the women did not have to walk for miles to fetch water. So all houses now get tap water. While the rest of Akola faces scarcity this summer, villagers here are relaxed because the women members decided to harvest rainwater to recharge wells and bore-wells.

“We won’t face water scarcity,” says Santosh Ghodke, a gram sevak (assistant) who aides the panchayat members in drafting projects and completing bureaucratic procedures. “In the past four years, we’ve won several awards instituted by the government,” he says with obvious pride. “We’ll utilise the prize money to make underground sewer systems, and improve roads and productive assets.”

The all-women panchayat has also shifted the village to organic farming. “We follow biodynamic farming,” says Jyoti Pagdhune, a widow, whose husband died two years ago. “It reduces our production costs,” she says, adding, “it also fetches better prices for our chemical-free farm produce, be it cotton or soybean.” Jyoti, a mother of two, has taken admission in a distance education course this year, thanks to the support from the village veterans.

A majority of the villagers have been to school, and they understand the importance of education. So they scouted for a good teacher, and when they found Tulshidas Khirodkar who matched their requirements, they fought for his transfer from the nearby Danapur village school to their own village. “The villagers were so insistent that I had no option but to come here,” says Khirodkar. “They take complete care of us.”

When they found their children sitting on the floor in the village primary school, all the villagers - from landless poor to the big landholders - contributed small sums to buy desks and benches for the students, and beautify the school premises.

Gordha is leading by example, and a few villages in the vicinity are following its footsteps. A village five km away, Hiwarkhed, for instance, elected its sarpanch unopposed last year. Hingni, 10 km away, too has adopted the consensus model. “Gordha is a role model for us,” says Prakash Patil, from Hiwarkhed.

The village owes much of its success to communal harmony. A centuries-old shrine of Hazrat Shahdawal Sahab, which is open to all, gives them strength to overcome problems, says Samiuddin Mumtazuddin Inamdar, 25, a villager. Paradoxically, just a few km away is Belkhed village, which witnessed clashes between Dalits and dominant castes four years ago during Pola festival.

“Progress follows where there’s unity and a collective consensual vision,” says Shankar Tohare, whose wife Mainabai is deputy sarpanch. “Most feuds are a fall-out of the political divides created by leaders. We avoid such divisions.” Even as the country braces up for what would be one of the fiercest Lok Sabha elections, Gordha demonstrates that democracy is not merely a numbers game.

![submenu-img]() 'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case

'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

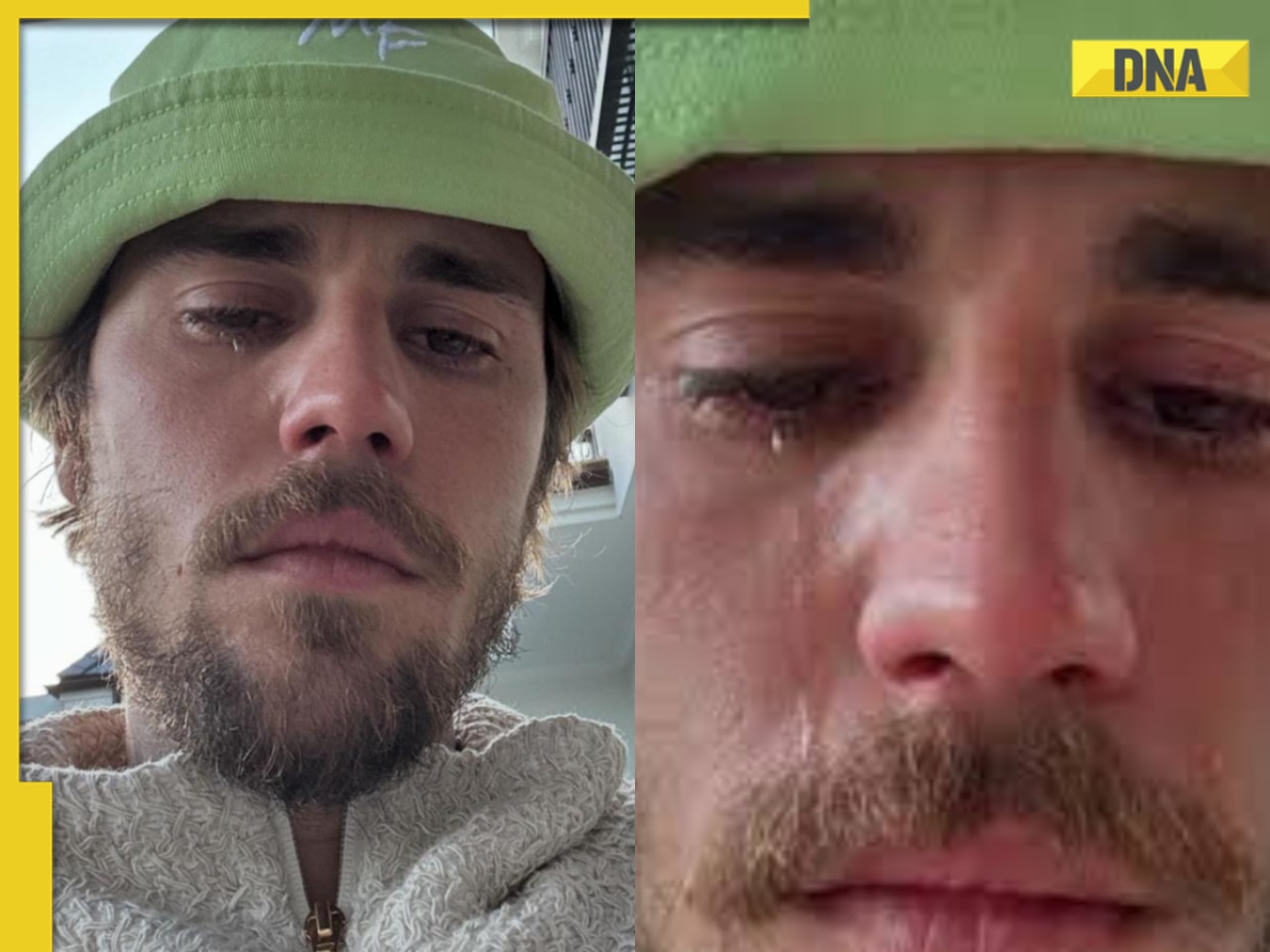

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)