In this interview, Raghuram Govind Rajan speaks to R Jagannathan and Vivek Kaul, on the current financial crisis in the United States and the impact it will have on the world at large.

“If India had a crisis of the magnitude that is hitting the United States, I would say God help us,” says Raghuram Govind Rajan, Eric J Gleacher Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at the Graduate School of Business (GSB) University of Chicago. Rajan was the chief economist of the International Monetary Fund between September 2003 and January 2007. He happened to be the youngest person ever to hold this position. Rajan is also the co-author of Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists, which he co-authored with fellow Chicago GSB professor Luigi Zingales. In this interview, he speaks to R Jagannathan and Vivek Kaul, on the current financial crisis in the United States and the impact it will have on the world at large.

Huge chunks of the US financial sector are being bailed out by the US taxpayer. Do you think capitalism will ever be the same again?

Capitalism has been through crisis before and I have true confidence that it will survive this one as well. The nature of the bailout is still being debated, negotiated, etc. Clearly the kind of mindless regulation that went on before — perhaps an excessive faith in markets, where participants had perverse incentives — will abate. Now it will go a little bit too much in the other direction for some time. We will regulate too much. We will prevent certain activities and over time will realise the cost of excessive regulation. Then we will swing back to deregulation.

These swings have been there in markets for centuries, so we will see some of that. I would not panic overly but I would say this is certainly a very black mark against the people who believed in excessively free unregulated markets.

Nevertheless, do you see this crisis as a fundamental threat to the whole idea of capitalism in someway, because in India the leftists are rejoicing, saying, we told you so

I have often made this point and I will make it again. The extreme version of the no-market philosophy is where North Korea is. Would you prefer to be in North Korea today or in South Korea? Most people who are sensible would prefer South Korea to North Korea.

Capitalism makes mistakes and we have to learn from those mistakes. I have been saying for years that there is too little regulation in these financial markets and we need more and better regulation. Now that doesn’t mean that you stifle the market and say that markets shouldn’t arise at all, which is the view of some people on the extreme left.

What we need is a balance between regulation and free market forces. What we have had in the US is too little balance on one side. What we have in North Korea is too little balance on the other side.

Do you think that the current $700 billion package will do the trick?

I don’t think the package will pass in its current form. My guess is, it will be much modified even by the end of the week (The interview was recorded on September 24, 2008).

And what we would see is some version of it. We also need a programme to add more capital into the banking system. It’s not just about buying these assets. The banking system needs to be recapitalised. The more it comes from private sources, the better.

Therefore, if that recapitalisation takes place and if some of this buying of assets is done successfully, it is possible to re-float the system over the next year. If it doesn’t work, then we may be even in for a more prolonged downturn.

In the recent crisis, we have seen mostly the investment banks going belly up. You have Bears Stearns and Lehman Brothers. And Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have decided to become full-fledged banks. So is that really the problem or is there something else?

In a panic, the guys who have ties with the government have the best chance of surviving. If the government is willing to write unlimited cheques to you then clearly you have no chance of going belly-up. And that’s the case with commercial banks because they have deposit insurance. So the depositors are not going to run because they know that deposits are insured. The commercial banks also have much better access to the discount window than investment banks. Finally, large commercial banks are deemed too big to fail because they are so well connected into the payment system and hence, by and large, commercial banks are much better connected to the government.

There is also a historical difference in activities. Investment banks are not well-placed to deal with illiquid assets, while commercial banks have historically had illiquid assets on their balance sheets. So, for investment banks, it was a whole new ballgame having illiquid assets on the balance-sheet and not being able to finance them. The commercial banks have been better suited partly because their traditional business is to deal with illiquid assets. But if you look across the board, it’s not clear that the commercial banks have made any wiser decisions than investment banks. They have made as big losses, in fact more. I don’t think this reflects the superiority of commercial banks in making investment decisions, but the superiority of the funding model of one.

What explains the decision of the US government to let Lehman go under and then decide to rescue AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? Is there an inconsistency?

The guru of banking theory on this is Walter Bagehot, who was the editor of The Economist and lived in the nineteenth century. Bagehot said “keep them guessing.” Most central bankers have agreed that this is the right thing to do, but you can’t make it completely based on the whims of the central bank governor.

Fannie and Freddie were to big too fail. Lots of people had pointed that out before. But nothing was done about it. So that was a disaster which was well anticipated.

In the case of Lehman, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury had decided that they had to draw a line somewhere. They did not want people to have the perception that they bail everybody out. They thought Lehman was the ideal test case because it had had enough time to get its house in order. But they discovered that once they let Lehman go, the markets focus turned on AIG.

The regulators did not know that AIG was problematic. This was because of lack of coordination among regulators. It turned out that AIG was a big player in a variety of swap markets. The regulators felt they had to go in because if AIG failed too many other institutions would have problems.

Why didn’t the regulators latch onto what was happening? Or is it that one regulator doesn’t know what the other is doing?

A little bit of that. The coordination among regulators even here has been quite deficient. And the authority has also been lacking. Only recently the Treasury has proposed to keep Fed in charge of financial stability, which means that it would have the ability to look at the large systemically important financial institutions.

In fact, this is what my report has suggested for India. That the high-level coordination committee should be more formal and that it should keep a constant eye on large conglomerates, with the authority to act. People are saying you are adding another bureaucratic layer. I am saying nobody really has the authority to act right now. Each one has their own authority. You need an empowered sort of body to have the responsibility for the entire financial system and it shouldn’t be implicit as it is now implicit in the RBI. It should be explicit and that’s why we suggest this Financial Sector

Oversight Agency precisely to avoid problems like AIG..

What’s the lesson in this for India?

India needs a number of reforms on improving the financial infrastructure, to make sure that the kind of problems that arose in the US do not arise here, and if they do, we can tackle them.

For example, we do not have a functioning bankruptcy code. So if a firm gets into trouble it’s very hard for the firm to be resolved in a very efficient way. Going to the BIFR and things like that take years and we haven’t had a good system to replace it as of now.

If India had a crisis of the magnitude that is hitting the United States, I would say God help us. We don’t have the capacity to deal with it. We need to build that infrastructure. The infrastructure, for example, to deal with financial institutions is at this point completely opaque I don’t know whether we have in place the systems to resolve a large bank if it fails. We have dealt with small bank failures. But what if a large bank fails? I know that is not a possibility we are contemplating. But we should think about these remote possibilities.

One of the points that my committee has made is the low quality of human capital in public sector banks in some of the newer areas like risk management and derivatives. This is based on complaints made by CEOs of public sector banks themselves. They do not have the capacity to recruit high quality talent. So if you do not have people at the top who understand risk management, who understand derivatives, etc, you can’t close the economy to these forces because they are there in your face everyday.

So our whole point about revitalising the public sector is to increase the quality of its human capital and ensure the banks can compete. The danger of not doing it is the fact that you will have the value of public sector assets erode in the same way as we have seen erosion for Air India and Indian Airlines. Of course, the vested interests are jumping up and down. The public sector unions are saying this is terrible. I don’t see how on earth is it terrible if we say improve the quality of your management and their incentive structure. The employees will benefit both in the short and long run. More to the point, the nation will benefit.

The public sector banks may lack the high quality managers who might understand risk etc, you can’t say the same about the US guys who went belly up anyway?

Talent without right incentives and regulation is also useless. Let’s take the right lessons from it. That’s precisely my point. Let us not argue that the dumber the guy you have on top the better it is. That is a silly statement. You need smart guys. But you need smart guys to be incentivised towards doing the right thing and being regulated to doing the right thing. And this is why I feel that a certain amount of intrusive regulation is fine.

What does this crisis mean really for global economic growth?

If an appropriate package is devised, the credit crunch could be short and mild. If a package is not put together(which I doubt, because something will be put together), or it does not work, then you could have a deeper and more prolonged credit crunch, which would keep the US close to 0% growth for the next year or two. And that certainly would be a burden for the world economy. There are also knock-on effects of the lack of confidence in the financial sector. For example, if you look at the direct effects on India, all these grand plans to make international acquisitions have to be put on hold because of the absence of financing.

Do you see some knock on effects of the slowdown on Europe as well?

The euro area has been slowing down. The United Kingdom has been slowing down. Therefore, the knock on effects certainly are there. Also, remember that a lot of European financial institutions bought into these stocks.

So will we see some kind of similar level of failures in Europe as well, which we don’t know about yet?

Part of the question that people have been asking is whether European institutions have been writing down their assets appropriately. Are they holding them at overvalued prices? The other issue is how widespread is it? We already know that UBS has had significant problems. We have had some problems in Germany and there could be more problems. But in general it could be spread widely enough so that it can be absorbed more easily.

What’s the prognosis on the dollar? After all these bailouts and the huge amount of fiscal expenditure, will the dollar hold up?

Think about the size of this. The $700 billion package that is being talked about is not a direct expenditure of $700 billion, presumably the subsidy element is $100-200 billion.

Even if it’s $300 billion, that comes to 2% of the US GDP. And remember it’s a one-off thing. A 2% addition to the country’s debt is not going to make the difference between life and death on the fiscal front. Even given its size, the net amount that will be spent on this is clearly a rounding error.

I think more important than this will be whether it is an Obama presidency or a McCain presidency. They have fairly different plans on spending and fairly different plans on how they are going to raise the money.

The greater fear from the dollar’s perspective is whether people lose confidence in US financial assets. And that’s a greater concern than the additional fiscal burden.

Should India be hastening to open the financial sector in the context of what has happened recently?

A lot of ink is spent on whether we should open or not. Now that is a debate that is clearly over. We are already very open. If you want to take out $2,50,000 today you can. Nobody is stopping you. The RBI has allowed you to do it.

Current and capital account convertibility is substantially free. What is probably not free is freedom to take over banks.

Many ownership restrictions in India are used to create rents for a lot of domestic players as opposed to improving efficiency and stability. And that I find problematic.

We should think about which regulations are really necessary for efficiency and stability and remove the regulations which are only there for creating rents.

Think, for example, that we haven’t got any foreign players in the asset reconstruction company business. We deliberately keep them out. When a financial system is in crisis we have a lot of non-performing assets (NPAs) that we may want to get rid of. At that point of time it is very hard to imagine that there would be domestic players who are also not a part of the same crisis and don’t also have their balance-sheets full of NPAs.

So it is very important to have a foreign player who can bring in capital at that moment and buy NPAs from domestic players who are hit. The logic is the same as sovereign wealth funds going to the US and buying equity there. They are outside players who are not hit and, therefore, they have the capital to revive the system.

Banks have, till recently, been growing assets very fast in India and there is an expectation that there will be an increase in NPAs. Keeping that in mind, do you think that foreign takeovers will be a good idea?

There is a problem in having a domestic banking system dominated by foreign ownership but there is no harm in starting with very small banks. What we need is a mixed banking system with some public sector banks, some private sector banks and some foreign banks. But we should make sure that we are not putting artificial conditions on any of these, so that all can compete. To make this possible, you have to take the shackles off the public sector. Often the best way to take those shackles off is better governance and a little more distance from the government. Those will be necessary in order to make them compete more effectively.

For the foreign sector, I would say let them in through the small banks. And, if they can grow them through better service, more efficiency, etc, more power to them. Now remember they are allowed to take over small underperforming banks already. Hence, the real issue is whether they can take over small healthy banks.

We have had a year of profligate spending by the government. Can we afford it?

On the fiscal side, you have to write off a little bit because of election year populism.

The question is: can this set up longer-term problems by making the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act a notional target?

We already have so many items off balance-sheet. The oil losses have been dumped into oil company balance-sheets. Also, we are building up obligations for the future. For example, the way the farm loan waiver is going to be paid for. So I think, there is a real possibility that if we do all the math, and come down to the actual FRBM improvement, we haven’t done that much.

This is one place where the commentary in India doesn’t fully appreciate how much the difference between India and China is.

China, because it doesn’t have such rampant middle-class subsidies, has managed to have a much more aggressive focus on public investment. But in India, with our budget being strained just by spending on all these things, we haven’t had significant public investment. Because we don’t have room on the public budget, we keep saying public-private partnership, which some times mortgages to the private sector things, which the public sector should be doing. It gives tremendous rent to the private sector as a result.

There is a real concern in India that government in India is not doing enough of what it should be doing. I don’t agree that we should overspend and run large deficits but I think we should bite the bullet and cut back on subsidies where we can for the larger good of ensuring public investment into agriculture, roads, etc.

How do you see India’s growth and prospects over the next couple of years?

We are little bit like the grasshopper —- we have fiddled around in summer when we haven’t undertaken the reforms we needed, partly because of coalition politics. And we are going to see how well we did in summer as the winter comes. But India will do fine. I don’t see us falling of a cliff or anything.

Is growth going to slow down to 6-7%? We had a similar slowdown in the 1990s after years of fast growth…

Seven percent growth is not bad. We are going to see a little bit of a slowdown, and a widening external deficit, but we have the reserves to weather the turmoil. But our industries will have to make adjustments given slowing foreign growth.

The question in the mid-90s was whether industry had invested too much too fast. And they had excess capacity. That seems to be less of a concern now because tremendous growth has eaten up capacity quite a bit. So the real issue is whether we are growing above potential, which is what the RBI thinks and is raising interest rates to quell our growth a little bit. The problems now are different from what they were in the mid-1990s. That is not to say that we shouldn’t be careful in monetary management, because these are delicate times.

You mentioned that finance for Indian takeovers overseas may be difficult to get...

The financing for takeovers will be hard to come by, which means people will have to do a much better job in valuation. That said, with industrial countries in deep recession, there might be nice opportunities. So if you have the money, this is not a bad time to look around to find some jewels. On the other hand, if you don’t have the money, you probably are not going to get it.

A lot of people are talking about the rise of Asia. Is this going to be turning point when countries in Asia would be calling the shots, especially countries like China, if not so much India?

There are some immediate issues which will weaken the US’s position. But the US is still a $14 trillion economy and China is maybe a $3.5 trillion economy. So, really in terms of weight in the international market, Chinese will have more of a say because they are so important in global manufacturing. But India, Brazil and Russia are still quite small. I don’t think we are going to see the balance of power turn overnight. But this is one more step, in the eventual shift in the balance of power.

r_jagannathan@dnaindia.net

k_vivek@dnaindia.net

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour

Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour![submenu-img]() This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...

This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax

Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...

This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy

Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy![submenu-img]() Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’

Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’![submenu-img]() Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive

Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets

IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru![submenu-img]() Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral

Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour

Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked

Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked![submenu-img]() This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

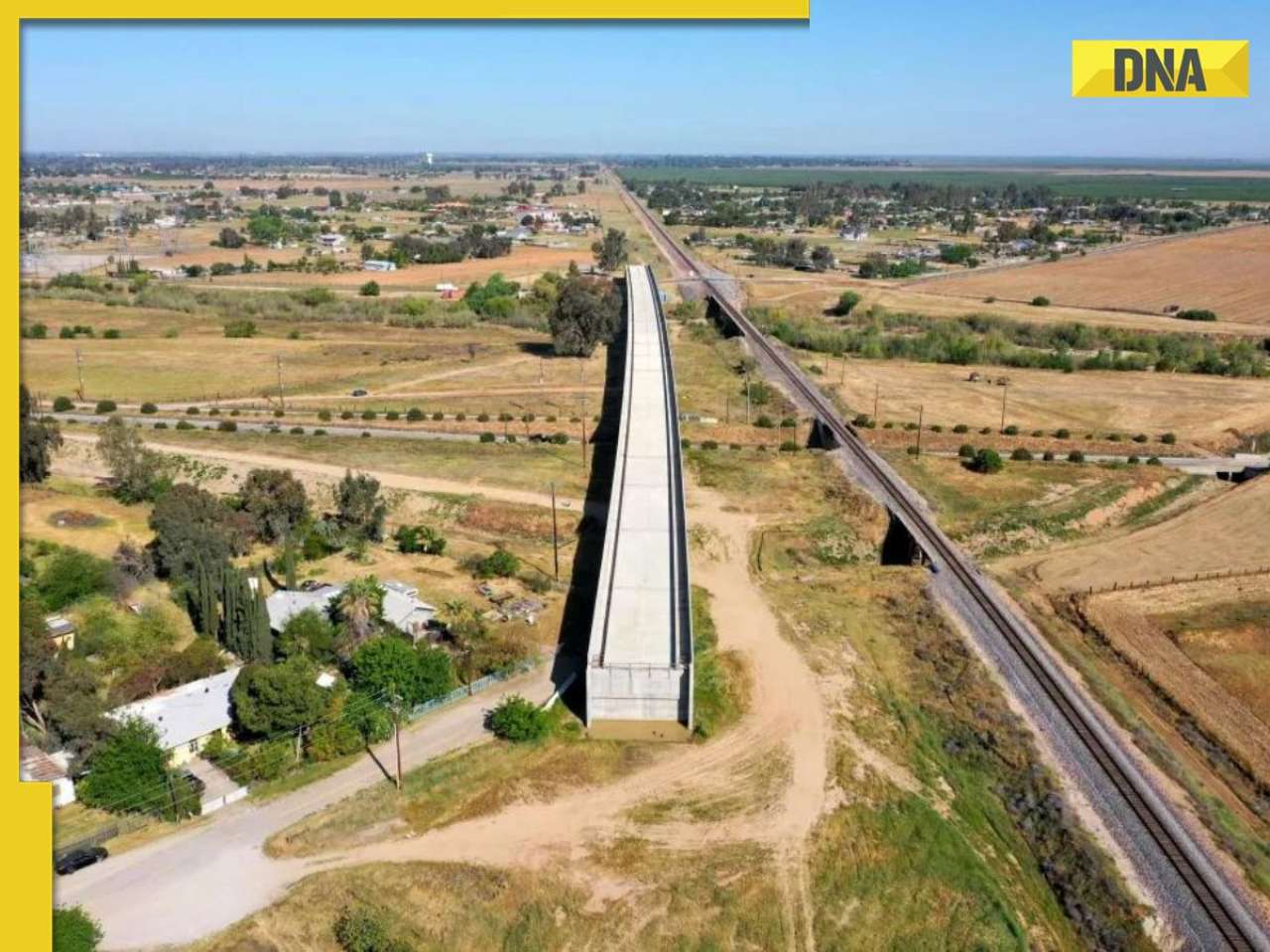

This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

)

)

)

)

)

)