Mumbai should probably give up its Shanghai dreams. Experts currently in the city, feel that having one dominant model for a city’s growth can be dangerous.

Mumbai should probably give up its Shanghai dreams. Experts currently in the city for a conference on the development of metros across the world (Urban Age India), feel that having one dominant model for a city’s growth can be dangerous. Skyscrapers, even though they are symbolic of the success of a metropolis, can break up and divide the city into smaller, exclusive pockets. Labonita Ghosh spoke to planners, academics and urban renewal experts on the challenges facing Mumbai, and examples from around the world that the city can draw from

Mumbai is a tranquil city

Ricky Burdett’s first comment is heartening. “Remember, Mumbai is not alone in this,” says the director of Urban Age, at the London School of Economics and Political Science. “The more I go around, to cities in South America and Africa, the more I feel that Mumbai doesn’t have many of the problems other cities do.” For instance, Mumbai has much less violence on the streets. “An estimated 80-120 people are murdered in Caracas on the weekends,” he says. “Yours is a tranquil city where a foreigner can walk around unthreatened. I wouldn’t think of doing that in Johannesburg; in Caracas, they wouldn’t let me out of the hotel.”

Burdett also believes Mumbai’s use of its natural resources needs a rethink. “Mumbai should be careful not to reach breaking point with its growing population,” adds Burdett, who has done considerable study on Indian metros. “It should not go the way of Mexico City which has sucked all the water from its lakes, and now the ground underneath is dry and making buildings crack.”

One of the biggest challenges the city faces, according to Burdett, is managing transport. “The notion that transport problems can be resolved with more private cars, is a blind idea,” he says. “You should build on your overcrowded public transport system instead.” So authorities need to crack down on private cars, like Singapore, which, through legislation, has limited the number of cars registered in a year. Shanghai allows no more than 500 driving licences a day. London has its congestion charge. “The private car solution can be a sustainable one only for another four or five years,” says Burdett.

Preserve the soul of the city

Andy Altman, a former planning director for Washington DC, says every time he visits Mumbai, he is “drawn to the city’s infectious energy and vitality”. No wonder Altman is concerned Mumbai, as it develops into a bigger metropolis might lose that. “The vitality of Mumbai is something organic,” he says. So the question is, in the bid for better development, how can one not lose that unique quality?

One way, he feels, is to address the question of the squalid living conditions of residents. “Given that 60 per cent of Mumbai is classified as a slum, getting basic services to the people and giving them adequate ‘life chances’ is critical to the growth of a city,” says Altman who, as top town planner, was responsible for the regeneration of many parts of the US capital.

But Altman does not advocate the route taken by US planners; he advises just the opposite. The urban renewal of the 1950s actually “wiped out” cities in the US by replacing the old with a new, more efficient system of living. “We built triple freeways through the hearts of our cities, destroyed communities and moved people,” he says. “We took the life out of our cities.” For instance, portions of New York under the renewal plan are dead today; places like Soho and the West Village, which have retained their old character and communities, are thriving. So now US builders are going back 50 years to what made their cities vibrant, and re-establishing them.

That’s what Mumbai planners need to keep in mind. “Highrises are not a bad thing, but they need to be integrated with the rest of the metropolis,” says Altman. Otherwise, they might break up the city into smaller, exclusive enclaves.

A city needs a dynamic leader

When Lindsay Bremner first arrived in Mumbai earlier this week, she was struck by the sight of people sleeping on top of their cars and pushcarts. “It was strange to see how people’s home and their livelihood was one and the same space,” says the architect who currently lives and works in Johannesburg. Which is why that space needs to be made liveable — and one way to do it, says Bremner, is to improve infrastructure. The city government’s primary responsibility is infrastructure, whether its transport, storm water drains or sewage, she says, “and it should be publicly-funded; in developing countries public infrastructure is seen as a resource for the private sector”.

Latin American cities have had some success here, says Bremner. Curitiba, in Brazil, had an environment-driven infrastructure agenda, which made for smart city planning. Enrique Penalosa, mayor of the Colombian capital, Bogota, also had a presentation at the conference, and has charted a successful transportation-driven infrastructure plan for his city.

One way of achieving a balance, says the architecture department chair at Temple University, in the US, is to ensure that officials who run the city, are directly-elected representatives. “People elect leaders who have no direct authority over the city,” says Bremner. “They should be vested with more powers.” The experiment has worked in Johannesburg.

“In Johannesburg, we had a directly-elected mayor who had executive powers over the city and used them,” says Bremner. “He became an emblematic leader for the city.” Perhaps Mumbai needs someone like that.

![submenu-img]() 'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case

'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

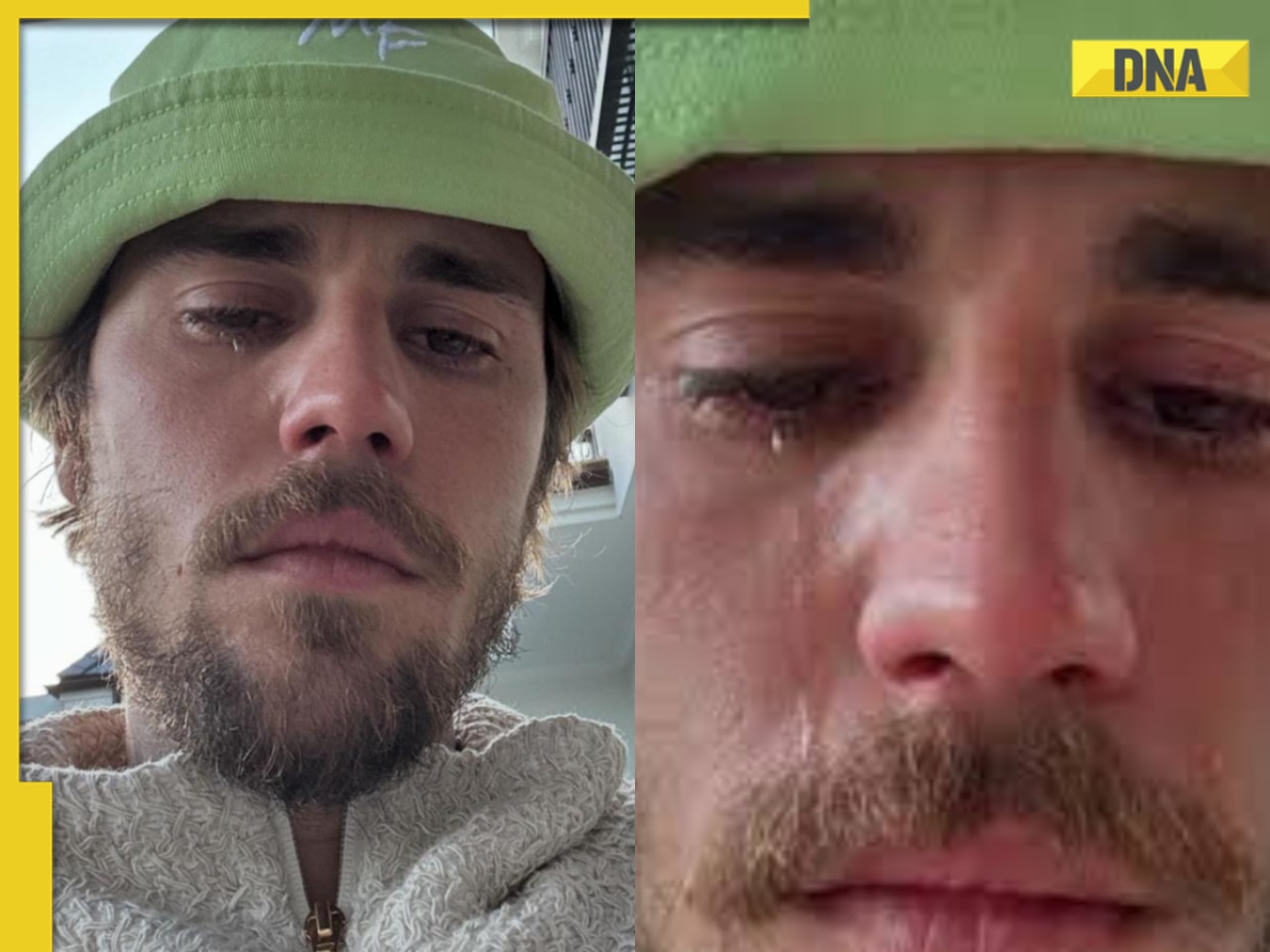

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)